By Paul Sisson

[O]nly one in four Americans has written down their end-of-life wishes in case they end up in a hospital bed unable to communicate — despite high-profile cases over the years that have plainly shown the emotionally painful, expensive and sometimes lawsuit-ridden consequences of not making those wishes known in advance.

A group of UC San Diego nurses and doctors is engaged in an effort to increase that ratio, building a wide-reaching campaign that started with just five letters and a question mark.

Operating like a guerrilla marketing group, albeit with the approval of two key hospital bosses, they began posting signs at both UC San Diego hospitals and its seven largest clinics. The signs simply asked: “WGYLM?”

At first, they refused to explain to others what those letters meant.

“We considered that a great victory to hear, that we were irritating people with our message. It totally primed them to be on the lookout for the answer,” said Dr. Kyle Edmonds, a palliative care specialist.

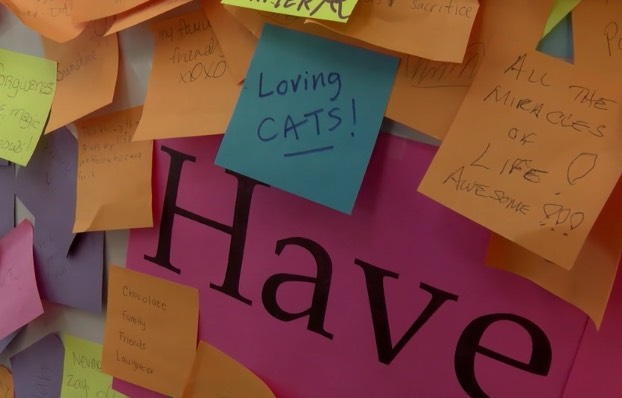

In March, the letters expanded from a five-letter bloc into the question, “What Gives Your Life Meaning?” There were small signs spelling it out and seven chalkboard-size whiteboards with the question written in large letters at the top. A bucket full of Post-It notes and pens was attached to each whiteboard display and very quickly, people wrote and pasted up their responses.

God has figured into many of those messages. There also have been plenty of first names, heart outlines and attempts at humor — including a note that said, “cheese biscuits.”

Some have been quite dark. Politics have been mentioned as well, including President Donald Trump and his proposed border wall.

The next step for the project group, after thousands of notes had built up, was to add the kicker question: “Have you told anybody?”

It’s not enough to answer the question for yourself, said Edmonds and colleague Cassia Yi, a lead nurse at UC San Diego. They want people to tell their loved ones — in writing — what matters most to them, including how they want to be treated upon death or a medical emergency.

The campaign’s organizers hope that getting people to think about the best parts of their lives will provide an easier entry point for end-of-life planning.

The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization recommends that everyone fill out an advance directive to make their wishes known in writing. Also often called “living wills,” these are witnessed legal documents that confer medical power of attorney to the person you designate if two doctors certify you are unable to make medical decisions.

Each state has its own form, and California’s asks people to specify whether they want a doctor to prolong their life if they have an irreversible condition “that will result in … death within a relatively short time or if they “become unconscious and, to a reasonable degree of medical certainty … not regain consciousness.”

This has been fraught territory, with many high-profile cases in the courts of distraught families wrestling over the decision to remove life support without any knowledge of the patient’s true wishes.

That includes the case of Terri Schiavo, who was left in a persistent vegetative state after a heart attack in 1990 caused severe brain damage. Her parents clashed with her husband, Michael, who asked the court to order her feeding tube removed in 1998 on grounds that she would not have wanted to live in such a state. Because she had no living will, it took years of very public legal wrangling before life support was disconnected on March 18, 2005.

Yi said she and other nurses feel this type of gut-wrenching stress every time a “Code Blue” page sends them scrambling for a patient who needs immediate resuscitation. Most of those patients don’t have wills or other written indications of their wishes in place, even though every patient is asked if they have an advance directive upon admission to the hospital.

“Advanced care planning wasn’t happening until people were coding out. There is nothing advanced about that,” Yi said.

Even before the current awareness campaign, Yi and her colleagues had worked with computer experts to add special categories to UC San Diego’s electronic medical records system that provide a single collection point for this kind of information. Previously, such details could be entered in dozens of different places, depending on the whims of whoever was taking notes at any given moment.

The project team also got the computer programmers to add a shortcut that allows caregivers to quickly access an advance-directive template.

Since the revamped system went live in February 2015, Edmonds said there has been a 469 percent increase in the number of patient charts that include some sort of information about end-of-life care.

But the project was not reaching every patient — or enough of the university’s medical staff.

Yi recalled a trip that some UC San Diego nurses took to the CSU Institute for Palliative Care at Cal State San Marcos. There, they saw “WGYLM?” signs and learned what the acronym meant. At the time, Cal State San Marcos was in the early stages of creating the “What Gives Your Life Meaning?” project.

The nurses thought: Why not adopt that program for UC San Diego as well? They liked that the operation could be rolled out in a provocative way and that it didn’t simply ask people to fill out advanced directives.

“It just makes an introduction in a more positive, intriguing light,” Yi said.

So far, nearly 1,300 employees in the UC San Diego Health system have taken the pledge to prepare their end-of-life documents and talk with their loved ones about these issues.

Sharon Hamill, faculty director of the palliative care institute at Cal State San Marcos, said the “WGYLM?” campaign has been held on that campus for three years in a row and has spread to sister campuses in Fresno and Long Beach.

She said the signature question was created by Helen McNeil, who direct’s the California State University system’s multi-campus palliative care institute, which is also housed on the San Marcos campus.

Hamill also said the message resonates strongly with people of multiple generations, including college students taking care of ailing grandparents or even parents.

“I love it when one of them stops me somewhere and tells me they saw one of the signs and were thinking about it all the way to class,” she added.

For more information about advance directives, go to nhdd.org.

Complete Article HERE!