By Robin Marantz Henig

If you make a choice to hasten your own death, it’s actually pretty simple: don’t eat or drink for a week. But if you have Alzheimer’s disease, acting on even that straightforward choice can become ethically and legally fraught.

But choosing an end game is all but impossible if you’re headed toward dementia and you wait too long. Say you issue instructions, while still competent, to stop eating and drinking when you reach the point beyond which you wouldn’t want to live. Once you reach that point — when you can’t recognize your children, say, or when you need diapers, or can’t feed yourself, or whatever your own personal definition of intolerable might be — it might already be too late; you are no longer on your own.

If you’re to stop eating and drinking, you can do so only if other people step in, either by actively withholding food from you or by reminding you that while you might feel hungry or thirsty, you had once resolved that you wouldn’t want to keep living like this anymore.

And once other people are involved, it can get tricky. Caregivers might think of spoon-feeding as just basic personal care, and they might resist if they’re asked to stop doing it — especially if the patient indicates hunger somehow, like by opening her mouth when she’s fed.

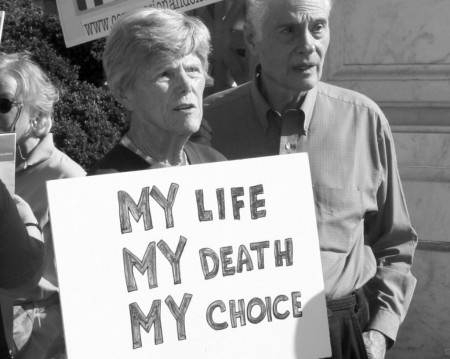

Conflicts between caregivers and the patient’s previously stated wishes can end up in court, as with the case of Margaret Bentley, which goes before the Court of Appeals in British Columbia on Wednesday.

Bentley, a former registered nurse, decided years ago that she wanted to stop eating if she ever became completely disabled. But she has now sunk so far into dementia that she needs other people to help her carry out her own wishes. And while her family wants her to be allowed to die, the administrators of her nursing home do not.

Back in 1991, Bentley wrote and signed a living will that said that if she were to suffer “extreme mental or physical disability” with no expectation of recovery, she wanted no heroic measures or resuscitation, nor did she want to be fed “nourishment or liquids,” even if that meant she would die.

Eight years later, at the age of 68, Bentley was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. She lived at home with her husband John, as well as a live-in caregiver, until 2004, when she needed to be institutionalized.

For a while, according to her daughter, Katherine Hammond, the family hoped she would just die peacefully in her sleep. But as the years dragged on and Bentley got progressively more demented, her husband and daughter finally decided to put her living will into action.

By this time it was 2011, and Bentley was living at a second nursing home, Maplewood House, in Abbottsford, about an hour east of Vancouver. Aides had to do everything for her, including diapering, moving, lifting and feeding her. So the decision to stop giving her food and water involved the aides as well as the Fraser Health Authority, which administers Maplewood House.

Someone — Hammond is not sure exactly who — resisted the idea of denying Bentley the pureed food and gelatin-thickened liquids that were her standard diet, especially because she seemed to want to eat, opening her mouth whenever they brought a spoon to her lips.

That’s just a reflex, insisted Hammond, who made a short video showing that Bentley opened her mouth even when the spoon was empty. “There she goes again,” the daughter says on the video.

In early 2013, a Superior Court judge ruled that it was more than a reflex, it was an expression of Bentley’s desire to be fed; he granted the nursing home permission to continue to spoon-feed her. Bentley’s family appealed, resulting in Wednesday’s court hearing.

Death brought about by the cessation of eating and drinking might sound scary in prospect, but it’s said to be relatively painless if done correctly. Most of the discomfort associated with it, according to a pamphlet issued by the advocacy group Compassion & Choices, comes from trying to do it in increments. Even a tiny amount of food or water “triggers cramps as the body craves more fuel,” the group writes. “Eliminating all food and fluid actually prevents this from happening.”

They recommend lip balm and oral spray if the mouth gets dry, rather than sips of water that can introduce just enough fluid into the system to make the process harder. And they counsel patience. It takes about six days, on average, for someone who stops eating and drinking to slip into a coma, and anywhere from one to three weeks to die.

Scholars have been tangling for years with the moral quandary of how to treat people like Margaret Bentley, who indicate, while cognitively intact, that they want to kill themselves when they reach the final stages of dementia. (NPR earlier covered the story of Sandy Bem, a woman with Alzheimer’s who took matters into her own hands before that final stage.)

In a recent issue of the Hastings Center Report, a prominent journal of bioethics, experts were asked to consider the story of the fictitious Mrs. F., a 75-year-old with advanced Alzheimer’s living at home with her husband and a rotating cast of caregivers. Early in the disease process, Mrs. F. had been “adamant” about not wanting to end up profoundly demented and dependent. She told her husband that when she could no longer recognize him or their two children, she wanted to stop all food and fluid until she died.

Mrs. F.’s cognitive function “was beginning to wax and wane,” according to the description in the journal, when she finally decided it was time to stop eating. But occasionally she would forget her resolve — she was, after all, suffering from a disease characterized by profound memory loss — and would ask for food. When she did, her family reminded her of her previous decision.

But they were torn, as were the aides caring for her. Which Mrs. F. should they listen to: the one from before, who above all else did not want to become a mindless patient in a nursing home? Or the one from right now, who was hungry?

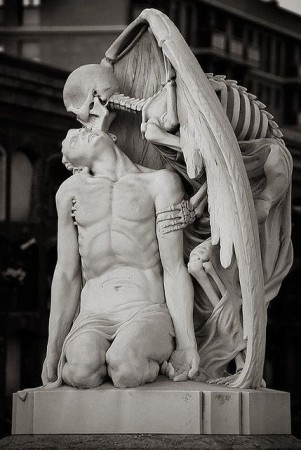

That’s the problem, really; part of what happens in a dementing illness is that the essential nature of the individual shifts.

“Mrs. F.’s husband was, to all appearances, acting out of goodwill in an attempt to honor his wife’s previously expressed wishes,” noted Timothy W. Kirk, an assistant professor of philosophy at the City University of New York, in his commentary on the case. “Doing so in a manner that conflicted with her current wishes, however, was a distortion of respecting her autonomy.” Kirk’s bottom line: If this Mrs. F., the one with the new, simpler identity, asks for food, she should get it.

As hard as it is to resolve moral quandaries like these, one thing is clear: they’ll be raised again and again, as the population ages and cases of late-life dementia soar.

Complete Article HERE!