By JULIE MYERSON

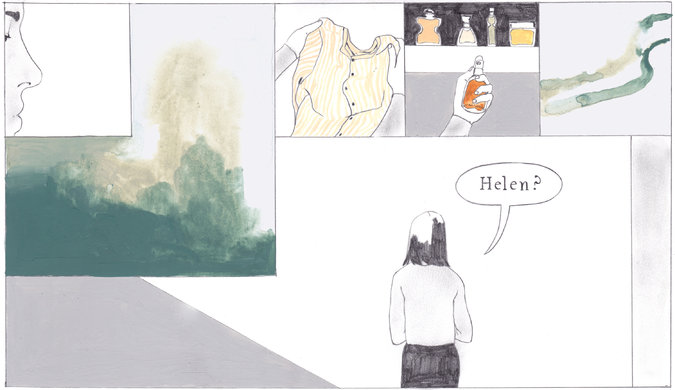

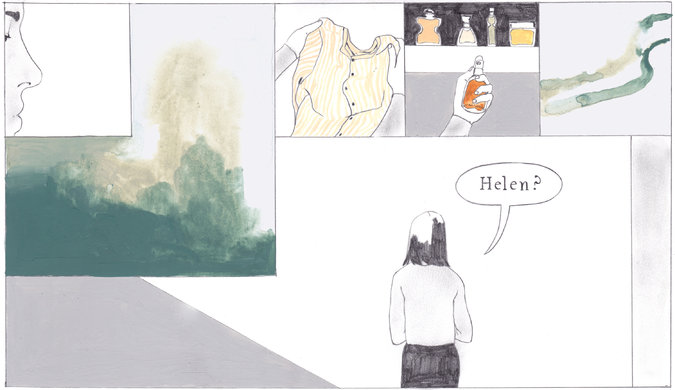

THE first time it happens is a dark winter’s afternoon, not quite a year after her death. I’m at my desk working, and there it suddenly is: sharp, glassy-green, with that faint, musky undertone that catches at the back of your throat.

I recognize it instantly: the scent that hung in our hall every time she came to supper. The perfume that clung to her coat, her scarves, detectable sometimes for hours on my babies’ hair after she’d been carrying and kissing them.

That first time, it’s a shock. Her perfume is something I’ve long forgotten (in her final months, mostly bedridden, she was beyond all that). But here it is — absolute and definite and quite overpowering. It lasts for three, maybe four minutes, long enough for me to get up and start searching the room for its source (my daughter, Chloë, has a few of her cardigans — did she leave one in here?).

Then, just as suddenly, it’s gone.

When I tell Chloë (who says that the cardigans have long since lost their scent), she rolls her eyes. “Oh my God, now you’re smelling dead people!” We laugh — and I soon forget about it.

Helen was my mother-in-law. She lived a happy, active life, but in her mid-80s her health and brain began to fail. After a couple of years of hip replacements and minor strokes, she died one warm April evening with her family all around her. As deaths go, it was probably a good one.

But in the weeks and months that followed, I was surprised at how often I’d find myself poleaxed by grief at the sheer fact of her absence.

Helen was in her 60s when I met her, a recent widow. A willowy blonde in an elegant camel-hair coat, she was a dead ringer for Lauren Bacall (“What nonsense!” she’d protest if someone said so, her eyes lighting up all the same). She was shy, but always well read, groomed and immaculate in her habits (and a tad judgmental about those who weren’t).

On our first meeting, waiting while her son — my new boyfriend — parked the car, she asked if I agreed that his recent attempt at a beard made him look like a used-car salesman. I burst out laughing and that comment set the tone for our whole relationship.

Helen was my ally, my champion (frequently even against her son, Jonathan). It’s hard not to love someone who’s always on your side; I’d never had that kind of approval from anyone.

When our babies came along, she threw herself into grandmotherhood. Her constant availability — to help out, to comfort, to babysit — was one of her most loving gifts.

The second time it happens, some weeks later, I am in the cellar, pulling wet clothes out of the washing machine. And there it suddenly is, filling the air around me. “Helen?” I say — and then blush.

I ask Jonathan if he knows the name of the perfume she wore. He has no idea. I ask his sister. “Something by Hermès?” she offers. At a department store perfume counter, I sniff a confusing number of bottles. Only one stands out — a touch of that glassy greenness: Calèche (and it is Hermès). But I can’t be certain.

At supper, a month later, all five of us around the table, the Bolognese being served, I ask, “Can anyone else smell that?”

“Smell what?”

“Perfume. Just like the one Granny used to wear.”

I watch their blank faces.

“You can’t smell it? Really? None of you can smell that scent?”

Several months pass before the next episodes: two in one week, both in my study. The second time, the perfume lingers for so long, perhaps 15 minutes, that I’m determined to get to the bottom of the phenomenon.

I pace the room, inspecting shelves, drawers, the sofa — there has to be an explanation! How can an ostensibly sane person repeatedly experience such a definite smell and fail to locate the source?

But I do fail. And then, just like every other time, it’s gone.

A friend, Mike, comes to lunch and I end up telling him the whole crazy story. I wait for him to laugh; instead he gives me a beady look. “Well, it’s a ghost, isn’t it?”

Jonathan makes a noise of exasperation and Mike turns to him. “What on earth else is it going to be?”

It’s true that I am interested in ghosts — they stalk much of the fiction I write. It’s also true that I did once, on a winter’s night long ago, see a form that startled me from sleep and which I have never been able to explain. But do I really believe in ghosts? I don’t think so.

What I do believe in — am perpetually fascinated by — is the gulf between what humans are capable of imagining and what may actually be there.

I tell Mike that even if I did believe in ghosts, it would be extremely uncharacteristic of Helen to haunt me like this. It’s not so much that she was resolutely rationalist (though she was), more that she’d be embarrassed to come back in this demonstrative fashion.

Later, I Google “smelling perfume of dead person” and find an excerpt from a book about “after-death communication” by an American academic and self-styled skeptic named Sylvia Hart Wright. She claims there is convincing research on the subject and cites the example of her late husband who, after his death, appeared to make frequent contact by turning electrical appliances on and off.

I email her to ask if she can account for my experiences. She writes back to say that my episodes are “perfect examples of a common phenomenon.”

“My gut feeling,” her email concludes, “is that when you smell your mother-in-law’s perfume, her spirit is visiting you in some fashion, trying to communicate to you her continuing closeness and support.”

A nice idea. I wish I could say that my own gut feeling supported it.

Next, I email Jay A. Gottfried, a neuroscientist who runs the Gottfried Laboratory at Northwestern University, which investigates the links between brain activity and sensory perception.

Professor Gottfried tells me that what I describe is known in his business as “phantosmia” or “phantom smells.” The sense of smell, he says, is our most ancient, primal sense and has “intimate and direct control over emotional and behavioral states.”

“This is especially true for personal, meaningful memories that tend to get stamped into our brains very robustly,” he explains. “Thus it is possible that a seemingly random trigger or thought — perhaps even outside your conscious awareness — has triggered some aspect of your mother-in-law memory.” In some ways, he says, “it is true that your mother-in-law is ‘visiting’ you, to the extent that your memory of her is strong, and that the vividness of her perfume makes it seem like she is there.”

I read that last sentence several times over. It seems reasonable. But could it explain so many episodes? And what about the persistence of the perfume, lingering often for minutes at a time: Can a triggered memory — a random sensory “thread,” in his words, snagged from the “patchwork” of the unconscious — do that?

I put all of this to him in a carefully concise email, and then add — because I can’t resist it — “I would just love to know: Have you ever, as a scientist, experienced something you feel you can’t explain?”

He doesn’t reply.

I decide to try another branch of science.

FLORIAN Ruths is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Maudsley Hospital. I know Dr. Ruths from attending a course he taught a few years ago. I am slightly embarrassed to approach him with such an eccentric-seeming inquiry, but Dr. Ruths’s reply is affable and serious.

“A sensory experience without an appropriate stimulus,” he explains, “is called a hallucination,” and these are “not unusual in grief reactions.” In less clinical terms, he tells me I “have been given a wonderful sensory memory cue that brings back your beloved mother-in-law in such an immediate and emotionally charged manner.” Maybe, he writes, “it is a very wise trick of your brain of maintaining such a fond memory of her, and an emotional connection to her.”

The idea of a “wise trick” of the brain is a seductive one. But the phrase “grief reactions” bothers me. I did grieve when Helen died, very much so, and for several months. But after five years?

If this “grief” now takes any shape, it’s a simple longing to see her again. How wonderful it would be to call her, hear her pick up the phone, shyly pleased, and to go over and sit on her terrace, drink a glass of sauvignon blanc and watch the boats slide past on the Thames, as we used to.

I recognize this for what it is: a natural nostalgia for the days when our children were small, when life seemed so uncomplicated, when so much still lay ahead.

But if this is just about my own, unrequited longing, then — Mike might ask — who exactly is the ghost? Could this be a case of the living haunting the dead, rather than vice versa?

I’m not a churchgoer or even strictly a believer, but realizing that I’ve allowed no possibility of a religious context for these experiences, I email my friend Giles Goddard, who is an Anglican vicar. He tells me he’s certain that “strange and inexplicable things” are regularly “perceived by the subconscious often with no obvious cause.” Like Dr. Ruths, he suggests it’s a normal part of grieving. He sends me a verse by Gerard Manley Hopkins:

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

Original, spare and strange, I like that. But I still find it hard to believe that this is a response to grief. Why would it suddenly come back at me like this?

“Maybe grief is the wrong word, then,” he counters. “Maybe loss?”

Loss. Isn’t that the hardest lesson of human existence? The finality of losing someone you love, of having them fall right out of your life forever: the cold and terrible permanence of it.

Intellectually, I comprehend that Helen is dead. But even after all this time, I’m still not sure I believe it.

It’s been weeks since I smelled the scent. Whenever I haven’t smelled it for a while, I begin to think it won’t come again. And I don’t know what I feel about that.

The other day, killing time on a rainy autumn afternoon on Oxford Street, I walked into a department store and, on a whim, went to the Estée Lauder counter. The sales assistant asked if I’d like to try the new perfume. I smiled and shook my head, picking up one bottle after another — with names like Beautiful, Youth-Dew, Pleasures — and sniffing at them.

I sprayed White Linen onto a card. It wasn’t far off: clean and citrusy.

“Is it a gift for someone?” the girl asked.

I hesitated. “I’m trying to find the one my mother-in-law wears.”

Sensing a sale, her eyes brightened.

“You don’t remember?”

“No.”

“You can’t ask her?”

“Not really.”

“It’s a surprise, then?”

I smiled. “Kind of.”

“Do you think that’s the one?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’s possible.”

Complete Article HERE!