Life after death is changing – thanks to scientific innovation. The best time to plan is now.

What happens to us after we die? It is one of the most profound spiritual questions, but also a practical puzzle. After all, whatever you believe happens to the soul after death – if you believe in a soul at all – there is irrefutably a body for someone to deal with. While there are many emotions that can make it hard to think about what you want to happen to your body, it need not be traumatic.

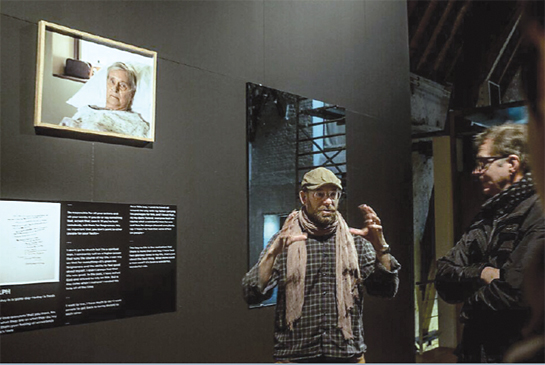

At least, that is what the researchers at the Corpse Project want to remind people. Set up last autumn and funded by the Wellcome Trust, this UK research programme has just published its first findings on what we might do with our bodies after we die.

I meet Sophie Churchill, the project’s founder, at a café in Queen Mary University of London. The goal, she tells me, is to help find ways to “lay our bodies to rest, so that they help the living and the Earth”. It’s not a case of being dispassionate but rather a quest to balance the social and cultural aspects of death with the scientific.

Sometimes, aspects of death that people initially baulk at can become more acceptable through conversation. One relatively new process, sold as a greener alternative to cremation, involves dissolving the body in heated alkaline water. “I was with 15-year-old urban teenagers, and you could see them scowling at the thought of being dissolved. But the more we talked about it and considered how odd it would once have seemed to go into machines and be cremated, [the more] they started to reconsider.”

Churchill points out that cremation, too, is a relatively recent phenomenon. The first official cremation in the UK took place in 1885, and it was only in the 1960s that the Catholic Church, for instance, accepted the practice and lifted its ban. Now, over 70 per cent of people who die in Britain are cremated.

Churchill is discovering that people can be open-minded, even if their beliefs are initially strongly held – though she admits that it may “still be a generation or two before new forms are accepted”.

“People will say, ‘Mourners always need a place to return to, to memorialise.’ But there are lots of people who do scatter ashes.” So, part of rethinking death might involve reassessing what we are comfortable with. I wonder if our general reluctance to talk about death makes it less likely that we will encounter different perspectives on how to deal with bodies.

Churchill’s studies with teenagers seem to support this. When asked to think about their own deaths, many of them were quick to engage with the idea, she says – “Being sent out to sea and burned in a boat, Viking-style, seemed to be very popular!” – and it was often their teachers who were more squeamish.

The Corpse Project is just one of a growing number of organisations committed to tackling the discomfort around death and dying. The Order of the Good Death was founded in 2011 by the mortician Caitlin Doughty and aims to “make death part of your life”.

The group of academics, funeral industry professionals and artists encourages people to educate themselves about dying, and even to become “death positive” by learning to accept and engage with their mortality. Its website covers everything from sky burials, in which corpses are left to be eaten by the birds, to how it feels to bury a relative if you’re a funeral director.

So what are the best options for someone wanting an environmentally friendly death? Until new methods such as dissolving become easily available, small tweaks can make a big difference. Doing cremation well, for instance, is important: the Corpse Project’s work partly involves investigating what sort of schedule allows crematoriums to operate at maximum efficiency.

If you want to be buried, it might even be a case of choosing a sustainable wood for your coffin. The Corpse Project is also investigating optimum burial depths and whether burials could be done strategically to enrich the soil where this is needed.

“But science never changes opinion by itself,” Churchill says. Luckily, every death is different, and can be a chance to invent meaningful rituals that incorporate innovative methods. The important thing, she stresses, is to think about it early, as one would with a will or life insurance.

“One day, this hand . . .” – she lays her hand on its back, limply – “. . . will do this. Twelve hours later, it’ll be a bit pale and clammy. And that will be it. The day will go on, with people going on having coffees, and so on.” She looks around her at the students milling in the sunshine. “To me, the last big challenge is to do that well.”

Complete Article HERE!