— How my mum tried to die on her own terms

Writer Marianne Brooker reflects on the onset of her mother’s multiple sclerosis , the ‘broad-shouldered, red-eyed’ work of caring – and, after doctors and politicians had failed to help, her mother’s decision to hasten her death

By Marianne Brooker

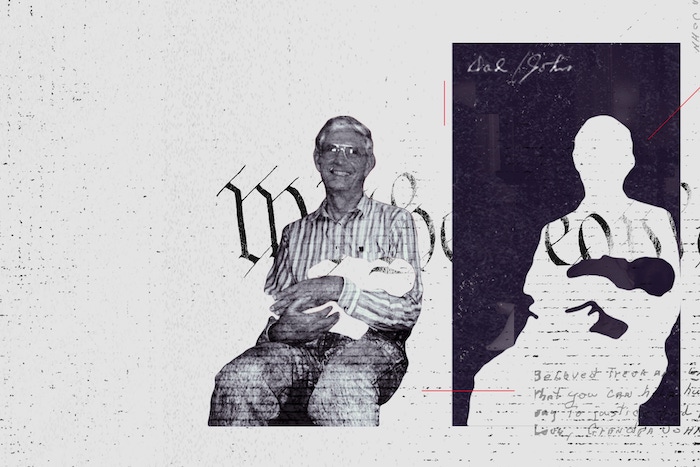

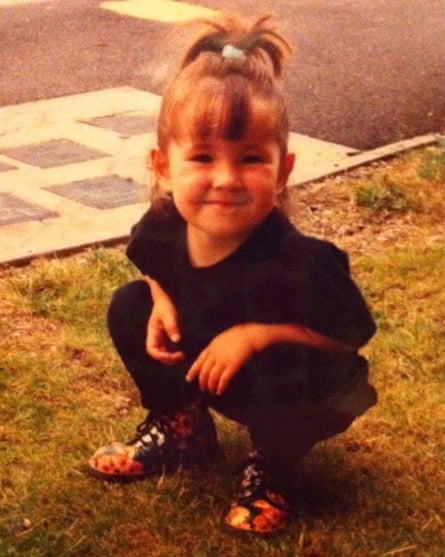

In the early 1990s, a year or so after I was born, my mum and I swapped my grandparents’ spare room for a council flat on the other side of town. Our new neighbourhood was tucked away in the looming shadow of a Procter & Gamble factory, the air around us thick with soap. I remember the flat being palatial, maybe because I was small or because memory can render pleasure in square metres, expanding the space with the strength of feeling. In a photo taken there when I was four or so, I’m crouched on the patch of grass outside, hair in a ponytail and smiling straight at the camera. Ahead of my time, I’m wearing a black T-shirt, black jeans and tiny, flowery Dr Martens – unquestionably my mother’s daughter.

Growing up there, I had a small circle of imaginary friends, some of my own making and some borrowed from the world (David Bowie chief among them). Each evening, I’d find two plates laid out for my dinner: one for me and one for Louis-Lou, my favourite made-up friend. My mum would wait for me to finish and go to bed before eating the second, untouched plate herself. I don’t remember this, but she often told the story, proud of her generosity and fortitude. As adults we’d joke: “How hungry are you, and how about Louis-Lou?”

Once, we wrote a letter to ET, another of my imaginary friends. To my surprise, soon after, I found a reply waiting on the doorstep. I’d only just learned how to read and knew instantly that his language of bright pink shapes and symbols wasn’t mine. Curious, we took the letter to our neighbour, the only person we knew with an alien translation machine – or so my mum claimed. I watched as she summoned the message up on its screen, the hard drive gently whirring as it translated the otherworldly Wingdings into words. I lost the letter many years ago and don’t remember what it said, but I still wonder at it: the sheer invention, the shared belief.

Play like this engenders a politics of alliance, not transcending our material conditions (impossible), but transforming them, plate by plate, letter by letter, dream by dream. We carried our determined fantasies into adulthood. Growing older, we welcomed in all that was strange and pushed at the world’s limits, always summoning some secret power.

In 2009, when I was 17 and my mum was on the cusp of 40, she started to stumble and slur. Despite her protestations, the GP was sure it was “just vertigo”. One day, she came home from the hospital with an MRI scan in a large brown envelope and a diagnosis: “I reviewed this lady today,” the letter from her neurologist to her GP begins, before adopting an unfamiliar language: “The oligoclonal bands are positive in the CSF and I explained to her that she has the primary progressive form of multiple sclerosis. Naturally this is distressing for her.” Naturally. About 7,000 people are newly diagnosed with MS each year in the UK. About 10% of those are primary progressive: symptoms can be varied but deterioration is persistent, with no remission and – at the time of my mum’s diagnosis – no cure (new treatments are now becoming available).

In the years that followed, my mum felt the sharp edge of disability under austerity and still rose to meet life with more fight, ingenuity and generosity than I can properly grasp. Busying herself with baking cakes to raise money for the MS Society and abseiling from the Forth Bridge, she made a mission of her disease. Her sense of agency and community ran deep. She didn’t just fight for rights but for means: making and supporting friends through online forums; picketing outside her local benefits assessments centre; lobbying members of parliament for greater support.

Her determination to live a good life was only matched by her determination to die a good death. In 2014, we visited our MP in a canteen in Westminster. She met his posturing with rigour, fanning out pages of research across the table and forcing him to confront what life was like for so many disabled and dying people. I watched her describe what her life was becoming – trapped, fearful – and what it would be like for her to die: painful, slow. Outside, her fellow demonstrators rallied on Parliament Square, demanding a change in the law to allow terminally ill people the right to an assisted death. But the laws didn’t change.

Before you can understand how my mum died, you have to understand how she lived. Sick and poor, she made a workshop of herself. When her hair fell out, she learned about wig-making and tracked down cheaper versions of her favourite styles from foreign wholesalers. When her teeth fell out, she learned how to mould dentures from a bright white and pink polymer. She duct-taped her feet to a tricycle so that she could feel the wind in her hair. She made an eye patch from an old bra. Necessity, they say, is the mother of invention. But there’s something else in this mix – a defiant kind of self-love: each act a refusal, each invention a gift. These inventions were a means of survival, in material terms and in more personal, psychological, even spiritual terms; they gave her a sense of vocation, pleasure, creation and repair.

When she couldn’t afford her first electric wheelchair, her friends and I clubbed together to buy one on eBay. One friend made a seat cushion and armrests from a cosmic blue fabric, emblazoned with gold stars. We stuck a transfer to the wheelchair’s old, heavy battery that read powered by witchcraft. I have a photo of her whizzing up the hill by her cottage, a shooting star with her dog trotting beside her, her new wig shining in the evening sun. She couldn’t be contained or curtailed; she was a woman drawn to the DIY and the don’t fuck with me. More than symptom management, she created a pattern for a whole other way of life: world-making against the world; surviving within and against the material conditions of scarcity.

Eventually, denied a livable life and a legal right to die, my mum made a choice within and between the lines of law. A decade after her diagnosis, when she was 49 and I was 26, she decided to stop eating and drinking to end her suffering and her life. This process is referred to as VSED: voluntarily stopping eating and drinking.

I discovered her plan by accident, through something offhand she’d said to a friend. Shocked, I listened and protested, clutching at every straw: more care, better care; more money, more time. There had to be another way. She resisted: her quality of life felt too thin, the pain too intense, the threat of losing the capacity to communicate her wishes too great. I looked for clues, catalysts, the last straw: why now? I’m not proud of my first feelings. Shock gave way to hurt: is such a thing even possible, does our love for each other mean nothing? Disbelief gave way to suspicion: is it that bad, are you that sick? I turned her decision into a mirror: am I that bad? We’d talked often about her wishes, but never about stopping eating and drinking. It felt cruel, unimaginable.

We negotiated a pause, time to think and – I hoped – avoid so stark an ending. I insisted she speak with her MS nurse and her GP. The strange prospect of VSED tore me in two, cleaving my head from my heart. I wanted my mum, for her own sake, to be allowed to die; but I wanted her, for all the world, to never be dead. The first felt abstract, fodder for debating societies and newspaper articles; the second lived in my guts and on the surface of my skin. For my mum, of course, the reverse seemed true. Being dead was no great fear of hers, but being compelled to live was killing her.

Searching online, I learned that although assisted dying is illegal in the UK, voluntarily withdrawing from life-sustaining treatment, food and water is not. Doctors are obliged to support patients in the usual way as new symptoms resulting from dehydration emerge and dying quickens. By this method, no one could intervene to hasten her death and no one could intervene to save her life. VSED might allow her the ritual of dying in a time and place of her choosing, with all its bedside tenderness; we wouldn’t break the law, even if the law did little for us.

My discovery knotted in my chest, I started making arrangements to move back home indefinitely. I had three jobs to extricate myself from and excuses to make. For my favourite of the three, I cycled to a nearby neighbourhood to lead a reading group. That week, we started Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts. In it, she describes going into labour, interspersing accounts of her experience with passages written by her partner Harry as he cared for his dying mother: birth maps on to death, each year of our lives like a palimpsest. It was the first time I’d read a narrative account of watching one’s mother die. Marking it up to teach, I underlined reminders for myself: “put a pillow under her knees”, tell her “that I loved her so much… you are surrounded in love”. Curious and selfish, I hoped that the book would reveal some great secret to me. Harry’s mother was “sick and broke and terrified”, not unlike my own. She chose her suburban condo in place of a Medicaid facility; “who could blame her?” She wanted to die where she had lived and to be crowded in by her familiar knick-knacks. Books like this enact their own quiet form of assistance; rallying around me like shields, windows and crutches.

I returned home in December, following some shorter weekend visits. Our pause had already stretched into months and I was sure we could stretch it further still. My mum’s cottage was piled with clutter. She lived in a time capsule of 70s melamine, torn lino and frayed net curtains. But she brightened it, filling every room with handmade treasures and trinkets. She expanded to fill each of its nooks and crannies, nurtured a sincere affection for its quirks and didn’t give an inch if anyone dare suggest she move somewhere on the ground floor, somewhere more accessible, more modern. “They’ll have to wheel me out of here,” she’d said for years. Insecure housing had chipped away at her sense of belonging, but this cottage was different; this home became hers, if only in her mind – and that’s no mean feat.

I loved it too: conversations at her dining table, deep into the night; the smell of freshly baked bread in the morning; the flower boxes lining the entrance ramp that a friend had built. The shade is well-known locally, marking buildings that are owned by one wealthy family. Every day, my mum’s green door insisted that her home did not belong to her. Every day, her ramp countered: in spirit, in belief, in every daily ritual of waking up and getting by – this was where she belonged, this house would hold her.

I remember one meal in particular, her almost-last. My mum took the lead, lighting the moment with the slow glow of mutual appreciation. Too often, I’d cooked for rather than with her, an admission that catches in my throat – what a rookie error. This time, I followed her instructions attentively: waiting to be guided by her, letting go of the things I’d do a little differently. We made a vegan quiche with chickpea flour, smoked vegan cheddar, onions, peppers, and what we affectionately called “fanny flakes” – nutritional yeast high in vitamin B12.

Care is broad-shouldered, red-eyed work: labouring against bedsores and cramps, lifting, cleaning, feeding. Like all things, care can break. In 2018, a survey conducted by the trade union Unison found that one in five surveyed care workers weren’t given the time to help their clients to the toilet. A similar number did not have time to prepare food or drinks. Nearly half said that they did not have time to support people “with dignity and compassion”. My mum wasn’t making her choice in a vacuum: there was no world in which she could grow older and sicker without struggle.

I was surprised to learn that hospices are only funded in part by the NHS – 30-40% in 2023. For years, their statutory income has been cut or frozen. For the rest they are reliant on donations, sponsorship, lotteries, legacies, grant fundraising and, of course, charity shops. Countless hospices advertise “sponsor a nurse” programmes, with small regular donations funding the cost of a shift or a palliative medicine. There’s a strange arithmetic to charity like this: your donation might help one or five or 10 patients in their final days of life. My mum was facing her voluntary death, watched over – in part – by volunteer “night sitters”, nursed by people whose work is funded through voluntary donations. The care we received was faultless (I say we, because I felt cared for too, by these people who listened, without judgment). But it could only alleviate so much.

Our last Christmas was slower and quieter. Pain clamped around her stomach and the lower part of her back or shot through her legs in sharp spasms. I associate that word with shuddering movement, but her spasms weren’t visible in that way. The movement happened below the surface, like an extreme cramp that often brought her to tears.

On Christmas Eve, she lay on the living room floor, making herself incredibly small. I’d seen pain crease and curl in her body before – winces, frowns, sharp inhalations of breath. But I’d not heard it like this, wailing out. I just sat there, my arm across her back. I got as close to this feeling as I could but couldn’t stop it, couldn’t even soften it. She took the heaviest pain relief she could and it knocked her straight out. She woke up the next afternoon, just in time for me to scoop out the fluffy middles of roast potatoes so that she could eat them.

Empathy teaches us that we can feel as one another – one’s own skin shakes, head aches and eyes water. But this attenuated feeling announces a distance between the person in pain and the person feeling its ripple. There’s a space between the person whose pain is intrinsic, from the nerves outwards, and the person whose pain is relational, from the world inwards. I wasn’t gripped by pain in the way that my mum was, but I chose to sit with it, with her. I couldn’t learn her pain from books; I couldn’t catch it from touch. But still it moved me and moved in this way, I could begin to accept her choice.

Pain renewed her resolve. For 20 days, we were suspended in an interval, a middle space between living and dying. At this temporary remove, my mum stopped eating and drinking and I found my way around a new type of work: navigating and advocating; lifting and bathing; checking dosages and picking up prescriptions; paying two lots of rent – hers and mine – as we transformed her home into a hospice. This interval was secret and particular – something between us – but common, too, an exception that exposed a fundamental condition of being a human in the world: we are interdependent, both separate from and reliant upon others.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!