By Randy Shore

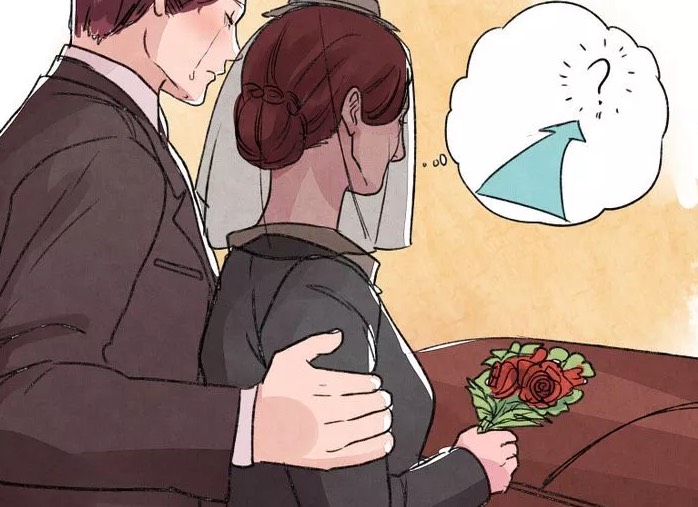

For Stefanie Green, the transition from baby doctor to helping people die was completely natural, providing care at different ends of life’s continuum.

“I (originally) chose maternity and I liked the fact that it was happy medicine, and really I can’t think of a better job on the planet than delivering babies,” she said. “I was in in my 20s when I started, so it felt (like) really familiar territory because I was also getting married and having kids.”

But helping people to die is not so different when the dominant emotion is not sadness, but gratitude.

Green has provided medical assistance in dying to 25 people over the past seven months, people who want to depart this life on their own terms in the face of painful and imminent death.

“The overwhelming emotion in the room when I provide this care is relief and gratitude,” said Green, a Victoria-based physician with 20 years experience in maternity care. “There is a release from suffering. The family is overwhelmingly grateful. The patient is overwhelmingly grateful.

“There is a real satisfaction on the part of the patient, who has made an empowering decision and been able to fulfill it after years of pain and hopelessness.”

Death review panel

About 200 people in British Columbia have opted for a medically assisted death since last June 17 when Bill C-14 created a legal environment for assisted dying. More than 740 Canadians died with medical assistance in 2016.

With six-plus months of data now in hand, the B.C. Coroner’s Service — with representatives of the health regions and the provincial government — plans a Death Review Panel for later this month to assess the new process. A report will be made public later this year.

As a young doctor, Green took careful note of celebrated B.C. right-to-die cases, including the 1994 death of Sue Rodriguez and, more recently, the 2012 B.C. Supreme Court decision that would have allowed Gloria Taylor the right to end her life. But it wasn’t until Green took a break from her maternity practice two years ago that she considered changing the focus of her career.

“When I realized that our laws were truly about to change and there was an opportunity to work in this new field I really began to educate myself,” she said.

There is a release from suffering. The family is overwhelmingly grateful. The patient is overwhelmingly grateful’ — Stefanie Green, provider of medical assistance in dying

After attending the 2016 conference of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies in Amsterdam, Green felt sure of her new course.

“Talking to people in the field, they were talking about choreographing the death,” she said. “Everything I heard sounded a lot like preparing for a birth. I really saw how those skills were going to be transferrable from one to the other.”

“There’s an art to making sure everything is going as smoothly and safely as possible during a delivery while still understanding you aren’t the most important person in the room,” she said. “I find that is the skill I take the most with me to end-of-life care.”

Public demand

The new law appears to have tapped public demand, as almost one person per day receives medical assistance in dying in B.C.

“When people come to me they have made a decision that they want this service,” said Green. “People are decided, courageous and very determined. They’ve made the leap.”

But not everyone who wants a medically assisted death can get it.

The federal law includes a criterion not found in the B.C. Supreme Court ruling, namely that the patient’s natural death “has become reasonably foreseeable.”

“It’s not exactly clear what that means,” said Green. “For someone who can’t make a clear case, it’s a difficult box to tick. I’ve had to say no to people and it’s the hardest part of the job, but I need to work within the law.”

The vast majority of Green’s patients are in the terminal stages of cancer and many of the others are in end-stage failure of the heart, liver or lungs. Most remain lucid right to the end, and importantly able to consent or decline the procedure to their final moments of life.

With some neurodegenerative diseases, the accelerating loss of mental capacity can muddy the waters.

“When people come too late in the course of their disease, it’s a problem,” she explained. “It may be that they are well enough to make the decision when I meet them, but they decline so quickly that they become confused and we have to stop the process.”

MAiD becoming normalized

Green is convinced many people will come to view medical assistance in dying — MAiD for short — as it becomes a normal part of medical care in a continuum that includes prenatal and preventative care, aggressive therapy for illness, hand-holding when treatments aren’t working and palliative care for those who seek comfort at the end of their lives.

She is adamant that the obligation to provide care does not stop five weeks or even five seconds before death.

“MAiD is just another part of that spectrum. Some people really need to fight to the last breath and some people really need to call the shot at the end,” she said. “The Canadian public understands very well what this care is and 87 per cent of them support it. I think that’s very humane.”

Complete Article HERE!