As a doctor, Diana Anderson has often used the phrase, but rethinks it after losing a loved one

By

“It was a good death,” the doctor said after one of our patients passed away while I was a resident physician on the night shift. The same line, I remembered, ends one of my favourite movies, Legends of the Fall, when Brad Pitt’s character dies at an old age from a bear attack.

My role throughout the night had been to adjust the medication. I would frequently check on my patient’s vital signs and update his family huddled at the bedside of the elderly man.

“How long will it be, Doctor?” they would ask each time I approached.

But I could not say for certain. “Most likely a few more hours, or less,” I would reply, based on the vital signs, the medications but mostly on a clinical gestalt I was learning.

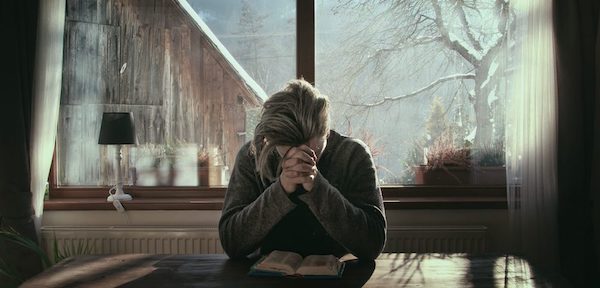

As a physician-in-training, I would go on to use the “good death” expression. At that time, it carried a meaning of death free from lines and tubes, medications administered for comfort and family at the bedside. But I question this expression now, after the death of Baba, my grandmother.

Baba lived alone in her house, feeding her backyard birds and squirrels religiously, and reading The Economist and National Geographic regularly.

My sister and I were lucky to have a grandmother by our side as children and even luckier to have her with us so far into our adult years as a guide and confidante. Baba and I kept in touch with frequent calls and weekly letters by mail. Through writing, she and I shared a unique bond. In the last letter I wrote her, I told her how much her life had impacted and touched us. For me, that meant inspiring a role working with older people.

Shortly after her 97th birthday, Baba fell and was no longer able to live on her own. I moved into her small house for two weeks as we secured a bed at a nearby nursing home. Even after working as a physician for days at a time without sleep, nothing could compare to the exhaustion I felt as a full-time caregiver.

Each time I changed her diapers, Baba became tearful, saying she felt humiliated and was a burden. Nevertheless, she found a way to laugh, recalling that she had changed my diapers as an infant and now “I am the baby who needs changing.” We chuckled over that each evening.

In the nursing home, her frailty seemed to increase rapidly. She was sad and cried often. Living in one room was “not really life,” she said to me a few days before she died.

She was suffering, but the best medicines seemed to be not what physicians could prescribe. It was the family visits, access to sunshine, nature views and the pet-therapy sessions – those brought smiles and a certain calmness that no pharmaceutical therapy ever could. The day before she died, she told me to “live life to the fullest, even if that means experiencing pain and heartache in addition to the joy and happiness.”

Baba wished often to simply fall asleep and not wake up and had concerns over how she would die. “I am ready to go,” she would say to me, “I have no more purpose.” I would tell her she was greatly needed, as the anchor to our little family – our supply of strength and endurance. She served as the one to go to for a listening ear and for her life wisdom. We were not ready to let her go.

One day, I got the call.

“You should come now. We think she is dying.” How many times have I made that same call to families, to tell them to come in but to drive carefully?

We did not drive carefully or slowly that night. A second call minutes later stated that, after some oxygen, she had regained her mental status and was speaking again, so perhaps I did not need to come back. The gas pedal was pressed even harder, the doctor in me knew too much to be comforted by those words.

Baba died 18 hours later.

Although she was still lucid when I arrived, she was in pain and visibly distressed. When I took her hand, she knew my name, but asked if she must be dreaming. “No, it’s not a dream, Baba, I am here.”

Overnight, there were limited orders for palliative medications. As a physician, I felt powerless and assumed my role as granddaughter. By morning I called my family and said they should come.

The day-shift palliative nurse immediately assessed the situation and ordered medications. She then asked me when to administer them. I knew that once we began, Baba would be with us less and less. My parents, sister and our dog, Bilirubin, assembled around her bed. Baba’s eyes lit up to the sensation of Bili’s furry coat on her hand. She knew our names. “Go ahead,” I said to the nurse.

Over the next few hours, Baba’s breathing slowed considerably. Dying takes time. Each time I thought her last breath came, she would then take another. When no breaths came for many minutes, I put my head on her chest and felt nothing – no heartbeat, no breath and no life.

After her death, I cried often for many days.

As a physician, I would call what Baba went through a “good death.” She passed away almost as she had wished, as if she had simply fallen asleep. She did not experience a massive heart attack or stroke, she did not endure trauma and she was not bedridden with painful lines and tubes. She had her whole family around, her hands were held and she was told she was loved. How could this be anything but a good death?

But as a family member, I wouldn’t call this a good death. It was simply a difficult death. There really is no other kind of death when you lose someone so close. Perhaps the last line in the movie should not have been that it was a good death, but rather, “It was a good life.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!