By Dr. Nick Busing

Living well and dying well are what we all hope for. As we face dying and death, we need all the support we can get. It comes from many places, but we all know about the challenges associated with crowded emergency departments, the wait for hospital beds, the inadequate number of community placements, the stress on home care, the shortage of personal support workers … the list goes on.

Most Canadians (75 per cent in recent surveys) want to die at home, but most cannot. Most palliative care today is still provided in the hospital. The reasons are complex and include the lack of adequate home care palliative services and the limited support available to families and caregivers as they struggle to support a loved one at home. Conversations about dying and death are often left too late, when families and friends are in a state of panic, and are unsure what to do, and therefore turn to the local hospital to help them out.

In my more than 40 years as a family doctor, I learned so much from my patients and their families. When I provided end-of-life care in the home, I often noted the critical role of the family and friends in providing support and care to the dying person. Those families who spoke to the dying person well before the last days to understand the values, wishes and beliefs that were important, coped better, as I am sure the patient did as well. This reinforced for me that dying, death, care-giving and loss are social problems with medical aspects and not medical problems with social aspects.

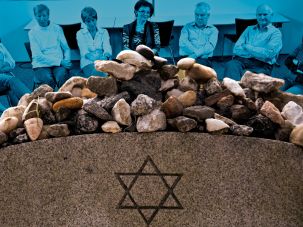

We need to mobilize our communities (person by person, street by street, neighbourhood by neighbourhood) to become better able to support each other as we age. Compassionate Ottawa, a grassroots organization, only two years old, lives by the following vision: A compassionate Ottawa supports and empowers individuals, their families and their communities throughout life for dying and grieving well.Compassionate Ottawa was started by volunteers, and is sustained by volunteers, all of whom want to help our community normalize discussions about dying, death and grieving so that we can reach out to each other to provide support when needed.

The compassionate city movement was started in the United Kingdom and advocates for the role of the community in providing support and care. The long-term goal for us is to achieve a new model of care for those dealing with dying, death and grieving. Compassionate Ottawa is working with schools, workplaces and faith organizations to educate them about planning for dying and death so that they foster resiliency at the individual level. We are conducting advance care planning (ACP) workshops with many community groups. Our compassionate city strives to be one that recognizes that caring for each other should not be left to the health and social services but is the responsibility of all of us.

Amongst its initiatives, Compassionate Ottawa is proud to bring the HELP project (Healthy End of Life Project) to Canada from its origins in Australia. This three-year research project, with funding from the Mach-Gaensslen Foundation of Canada and led by researchers at Carleton University, will work with two faith groups and two community health centres in Ottawa to develop the skills and confidence to offer, ask for and accept help near the end of life. We will identify the challenges and successes we encounter and hope to have lessons that will be of use not only in Ottawa but also in communities across Canada.

We cannot continue to look only to the government’s health and social services to support our friends and relatives as they near the end of their lives. A push for more resiliency in the community would be a great benefit to all of us. And downstream it would mean fewer visits to the emergency rooms, fewer admissions to hospital, less demand for experts, less costly care and, hopefully, a more satisfied and stronger population.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

In front of them stood Sally Kaplan, one of three facilitators present from the organization

In front of them stood Sally Kaplan, one of three facilitators present from the organization