By

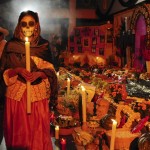

Ancient people ripped out teeth, stuffed broken bones into human skulls and de-fleshed corpses as part of elaborate funeral rituals in South America, an archaeological discovery has revealed.

The site of Lapa do Santo in Brazil holds a trove of human remains that were modified elaborately by the earliest inhabitants of the continent starting around 10,000 years ago, the new study shows. The finds change the picture of this culture’s sophistication, said study author André Strauss, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

“In reconstructing the life of past populations, human burials are highly informative of symbolic and ritual behavior,” Strauss said in a statement. “In this frame, the funerary record presented in this study highlights that the human groups inhabiting east South America at 10,000 years ago were more diverse and sophisticated than previously thought.” [See Images of the Mutilated Skeletons at Lapa do Santo]

The site of Lapa do Santo, a cave nestled deep in the rainforest of central-eastern Brazil, shows evidence of human occupation dating back almost 12,000 years. Archaeologists have found a trove of human remains, tools, leftovers from past meals and even etchings of a horny man with a giant phallus in the 14,000-square-foot (1,300 square meters) cave. The huge limestone cavern is also in the same region where archaeologists discovered Luzia, one of the oldest known human skeletons from the New World, Live Science previously reported.

In the 19th century, naturalist Peter Lund first set foot in the region, which harbors some of the oldest skeletons in South America. But although archaeologists have stumbled upon hundreds of skeletons since then, few had noticed one strange feature: Many of the bodies had been modified after death.

In their recent archaeological excavations, Strauss and his colleagues took a more careful look at some of the remains found at Lapa do Santo. They found that starting between 10,600 and 10,400 years ago, the ancient inhabitants of the region buried their dead as complete skeletons.

But 1,000 years later (between about 9,600 and 9,400 years ago), people began dismembering, mutilating and de-fleshing fresh corpses before burying them. The teeth from the skulls were pulled out systematically. Some bones showed evidence of having been burned or cannibalized before being placed inside another skull, the researchers reported in the December issue of the journal Antiquity.

“The strong emphasis on the reduction of fresh corpses explains why these fascinating mortuary practices were not recognized during almost two centuries of research in the region,” Strauss said.

The team has not uncovered any other forms of memorial, such as gravestones or grave goods. Instead, the researchers said, it seems that this strict process of dismemberment and corpse mutilation was one of the central rituals used by these ancient people in commemorating the dead.

Complete Article HERE!