(But not this year)

By Ryvyn

American culture is extraordinarily goal-oriented. This January, pause and notice the messages and expectations that are motivating you. Everyone creates goals regarding all aspects of life. In a single day, we set a vast number of goals to accomplish.

Adults have daily, monthly, or yearly goals for their job which may not be in alignment with their additional career goals. Athletes have intense levels of goal achievement and mindset work. Others may have spiritual or emotional goals. You might also have social, educational or even comfort goals, for instance, you want to purchase your own car or house or you want to start a family or gain independence. This list of goals can go on ad infinitum, but you have gotten the point by now and I’m beginning to feel overwhelmed by just listing possible goals.

Thus, I began polling people about their goals. I recently had a conversation with an acquaintance who stated their goal for 2024 was to add days to their family vacation. And then I sat there waiting in silence until it became uncomfortable, and I realized that was all they were going to say. I found myself in awe. I did not know what to say or how to respond as my mind whirled out of control with the list of goals I had set just because it’s TODAY and tomorrow isn’t promised!

My mind thought of my weightlifting, cardio, yoga, nutrition and meditation goals, the stack of books I plan to read, the podcast episodes and blog articles I want to do, the networking organizations and business researching, and any new certifications I think will benefit myself or my staff. Every year I want to see an increase in business profits. This breaks down to clients, social media and marketing goals, community outreach, pro-bono work.

As a member of my religion’s clergy, I have personal spiritual preparation and educational goals. Then there are relationships, family, and travel goals. And, underlying it all, my goal is to just handle what I’ve got scheduled and NOT take on any other GOALS!!!

I realized making New Year’s Goals is passe when I attended a business networking group recently, the host asked, “For those of you that are still into it, raise your hand if you’ve set goals for 2024?” Only about a third of the people raised their hand.

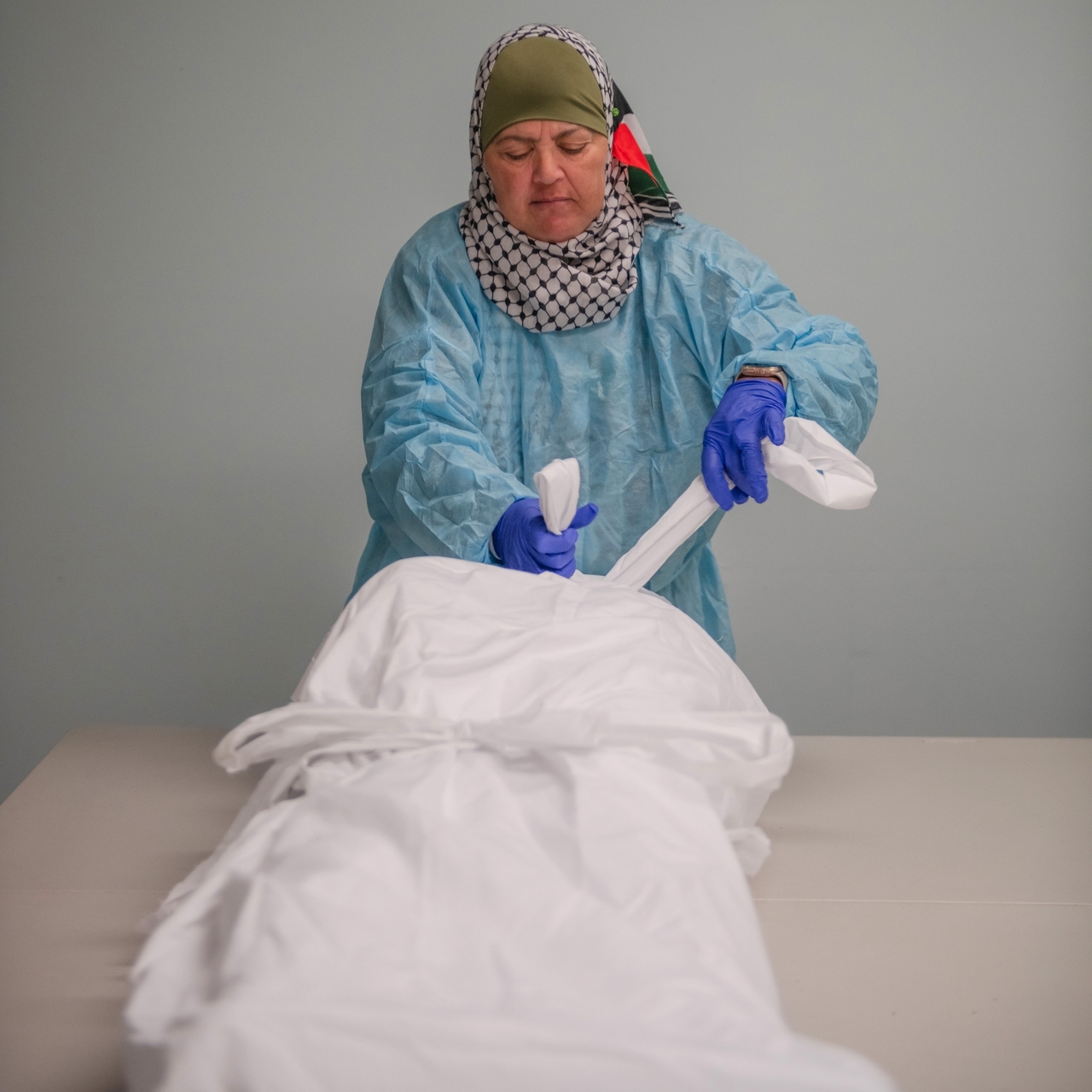

As a 2023 volunteer service goal, I committed to hosting monthly, virtual, Death Cafe meetings. For more information go to DeathCafe, According to the Death Cafe rules for these meetings, the only requirement is not to have a plan or agenda and to simply to hold space for the conversation. These are often sacred and sincere moments where people are vulnerable and share their thoughts and experiences. That required a personal commitment to do so. I see goals as personal commitments for growth, if you are not growing and learning you are stagnating.

One of my yoga certifications is in Brain Longevity Therapy Training. One of the tenets to a healthy aging brain is to keep it active. Activities like learning new skills, reading, socializing, movement work like balance and exercise all affect the brain. The brain and body need to be challenged to keep them working at optimal levels. However, growth is often a process that occurs even during dying and all the way through death. I often look at death, not only as transition but as an initiation. Death is an unknown and it takes preparation to face it in peace. Physician-assisted suicide, or “medical aid in dying”, is legal in eleven jurisdictions, the Commonwealth of Virginia is not one of them. As a Death Doula, I have been bedside with several people as they were actively dying. Some are aware and some are not, while all these deaths were medically regarded as peaceful. I do not know that they would classify as a “good death” if it were my own.

Holding space for Death is a growth experience. My ultimate goal is to have a good death and all my other goals reflect that. No, I am not actively dying, I am actively living. I am acutely aware of the fact that tomorrow is not promised and that gives the simplest of moments a glamor that most people do not see.

For example, walking my very elderly dog is its own growth experience in mindfulness. We walk slowly and methodically. Her eyes are not as clear now and it is obvious she has become mostly deaf. She avoids stairs or steep hills. She demands pets from any stranger and wants to sniff any friendly dog. She takes long pauses to sniff thoroughly between bushes and under benches. I have time to notice the clarity of the stars above and watch the diamonds of frost begin to form as we stand silently on the abandoned sidewalks in the winter darkness. The sweeping mantle of cold (or possibly arthritic joints) makes her knees tremble slightly.

We slowly walk along, allowing her to go as far as she wants and where she wants, until she spontaneously turns around and heads back. Some days she stands in the doorway to our apartment looking through as if she has forgotten where she is, cautious about entering. Other days, as she sleeps long and deeply, I will hear her whimper and look over to see her feet moving slightly, clearly dreaming of running and playing with other dogs or her humans. I know time is growing shorter for her, but we will face that together. I do not ever want her to feel alone or unloved. We can never accurately predict when a natural death will occur, so you must be ready all the time. Ushering a pet is much like a person. We sit and just be with each other. Sometimes I talk but other times it is just not needed. She just wants someone to be present and touch her. So much is conveyed through touch.

Time seems to shrink for elders. One activity, like a medical appointment or meeting a friend for coffee, can be exhausting. You think you have all the time in the world to accomplish the things you want but knowing Death can come at any time can make the experiences of life taste even more sweet. I do not like to repeat experiences, travel to the same places or even eat in the same restaurants because I might miss an opportunity! When I die, I want to know I lived my life to its fullest and took every opportunity to suck the life out of every single minute. This requires commitment, planning and setting goals.

Take a minute to consider if you knew you only had one year left to live. How would you live differently? What would take importance? Do you have the cash? Make it happen. Set those goals! Say the things that need to be said! Do the things you need to do! Heal the things that need attention! Let go of the past and be present! It’s time to outgrow your comfortable life and move into the adventure of living fully so that when Death arrives you are ready to take that journey with her without hesitation or regret weighing you down.

P.S. I offer a virtual Death Cafe meeting every month, for more information google “Death Cafe of Southside Virginia” or look us up on DeathCafe.com

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!