By Deborah Bach

Death and mourning were largely considered private matters in the 20th century, with the public remembrances common in previous eras replaced by intimate gatherings behind closed doors in funeral parlors and family homes.

But social media is redefining how people grieve, and Twitter in particular — with its ephemeral mix of rapid-fire broadcast and personal expression — is widening the conversation around death and mourning, two University of Washington sociologists say.

In a paper presented Aug. 20 at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association in Seattle, UW doctoral students Nina Cesare and Jennifer Branstad analyzed the feeds of deceased Twitter users and found that people use the site to acknowledge death in a blend of public and private behavior that differs from how it is addressed on other social media sites.

While posts about death on Facebook, for example, tend to be more personal and involve people who knew the deceased, Cesare and Branstad say, Twitter users may not know the dead person, tend to tweet both personal and general comments about the deceased, and sometimes tie the death to broader social issues — for example, mental illness or suicide.

“It’s bringing strangers together in this space to share common concerns and open up conversations about death in a way that is really unique, ” Cesare said.

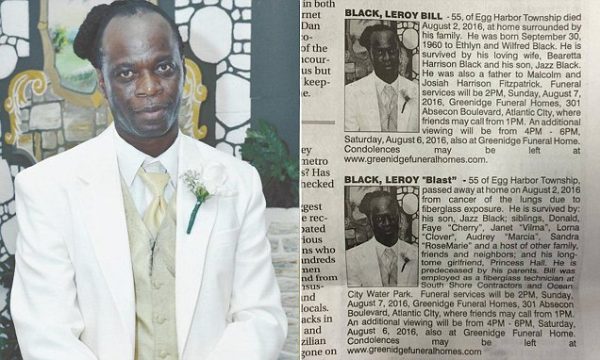

The researchers used mydeathspace.com, a website that links social media pages of dead people to their online obituaries, to find deceased Twitter users. They sorted through almost 21,000 obituaries and identified 39 dead people with Twitter accounts (the vast majority of entries are linked to or MySpace profiles). The most common known causes of death among people in the sample were, in order, suicides, automobile accidents and shootings.

Cesare and Branstad pored over the 39 feeds to see how users tweeted about the deceased, and concluded that Twitter was used “to discuss, debate and even canonize or condemn” them.

Among their findings:

- Some users maintained bonds with the dead person by sharing memories and life updates (“I miss cheering you on the field”)

- Some posted intimate messages (“I love and miss you so much”) while others commented on the nature of the death (“So sad reading the tweets of the girl who was killed”)

- Others expressed thoughts on life and mortality (“Goes to show you can be here one moment and gone the next”)

- Some users made judgmental comments about the deceased (“Being a responsible gun owner requires some common sense — something that this dude didn’t have!”)

The expansive nature of the comments, the researchers say, reflects how death is addressed more broadly on Twitter than on Facebook, the world’s largest social networking site. Facebook users frequently know each other offline, often post personal photos and can choose who sees their profiles. By contrast, Twitter users can tweet at anybody, profiles are short and most accounts are public. Given the 140-character tweet limit, users are more likely to post pithy thoughts than soul-baring sentiments.

Those characteristics, the researchers say, create a less personal atmosphere that emboldens users to engage when someone has died, even if they didn’t know the person.

“A Facebook memorial post about someone who died is more like sitting in that person’s house and talking with their family, sharing your grief in that inner circle,” Branstad said.

“What we think is happening on Twitter is people who wouldn’t be in that house, who wouldn’t be in that inner circle, getting to comment and talk about that person. That space didn’t really exist before, at least not publicly.”

Traditions around death and dying have existed for centuries, the researchers note. But increased secularization and medical advances in the 20th century made death an uncomfortable topic for public conversation, they write, relegating grief to an intimate circle of family and close friends.

Social media has changed that, they say, bringing death back into the public realm and broadening notions about who may engage when someone dies.

“Ten, twenty years ago, death was much more private and bound within a community,” Branstad said. “Now, with social media, we’re seeing some of those hierarchies break down in terms of who feels comfortable commenting about the deceased.”

Twitter use is still evolving, the researchers point out, making the site fertile ground for studying how social media is used for mourning in the future.

“New norms will have to be established for what is and isn’t appropriate to share within this space,” Cesare said. “But I think the ability of Twitter to open the mourning community outside of the intimate sphere is a big contribution, and creating this space where people can come together and talk about death is something new.”

Complete Article HERE!