— Why to Start Young

You’re too busy and alive to think about death when you’re young. “It always seems too early, until it’s too late,” declared the National Healthcare Decisions Day a few years ago. You want medical insurance for a sudden illness or injury. You ask our employer and government to offer retirement benefits to retire well. What about your hope to die well? Although you can’t control your future, you can plan for it.

By Sharleen Lucas, RN

End-of-life planning – also known as advance care planning – gives you a powerful voice if illness or injury leaves you unable to speak for yourself.

Hard to imagine, right? A day when an illness or injury steals your ability to make decisions for yourself. When you’re young and buzzing through your days of hard work and fun, death is an abstract, nebulous, and distant concern. Until a pandemic hits. Or you walk away from a nearly fatal motorcycle accident. Or your first child is born. Suddenly, death creeps closer and these moments make you think a little harder about life and death.

In 2020 according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, unintentional injury was the leading cause of death for 15 – 44-year-old Americans. No one knows what tomorrow brings, as the old saying goes.

But wait, isn’t thinking about death harmful to young people?

There’s no getting around it. When you plan for end-of-life care, you have to think about death.

I asked palliative care psychologist Dr. Dwain Fehon if it’s mentally healthy for young people to complete advance directives. As Associate Professor, Chief Psychologist, and Director of the Behavior Medicine Service for the Yale School of Medicine and Yale New Haven Hospital, Dr. Fehon has worked with countless patients of all ages facing mental and terminal illnesses.

His answers were enlightening. “When we can talk openly about difficult topics early in life, it’s just so healthy and helpful,” he expressed in his soft, kind voice. “It allows you to formulate ideas and to take in the thoughts and opinions of others so that you’re not alone or isolated with your thoughts or fears.”

There’s certainly evidence to support his words. When it’s explained correctly, most younger people want to talk about end-of-life issues.

In 2022, the American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care published a study of young people’s perspectives on end-of-life planning. The researchers talked with 30 white and Black participants. They found that 87% of them were comfortable talking about the subject and wanted to make their own end-of-life decisions. Even though the sample size was small, this research is consistent with other studies.

A study published in 2019 found that young adults welcomed the chance to discuss advanced care planning. They even wanted more information about it. Researchers found a significant improvement in their “self-perception of comfort, confidence, certainty, and knowledge” about death planning. They recommended more end-of-life talks with young people.

When you’re in your 20s and 30s, paving your path and making your own choices are top values. Planning for death empowers you to voice your opinion about the medical care you want if you can’t speak for yourself.

In 2015 researchers published findings from their end-of-life discussions with 56 young people between the ages of 18-30. They found each subject felt death planning was a valuable way to express their individuality. They also liked that advanced care plans can change and grow as they did.

Surprisingly, most young and healthy people are willing and even eager to talk about death planning.

“It’s interesting, thinking about death gets you thinking about life. There’s value in thinking about these things, and when we can think about it, it helps to reinforce a general acceptance within ourselves that death is a part of life. And it’s okay to talk about. It’s not a taboo topic that needs to be kept quiet.” — Dr. Fehon

His words reminded me of the young, healthy mortician Caitlyn Doughty, who founded the Death Positive Movement in 2011. Her goal is to help people of all ages break their silence about death. Topics kept in the dark create more confusion, robbing people of their power to understand the issue and make their own choices about it.

Death planning is actually about life

Dr. Fehon’s wisdom here continues. “In the palliative care world, we have a concept called double awareness,” he told me. “One component is life engagement, and the other component is death contemplation. The idea is to hold these two concepts in our lives. We can contemplate death and still be engaged in life.”

The lightbulb lit up in my head. Death contemplation can engage us deeper into life. This is why many young people like it. The young participants in these studies had the chance to clarify what they want from life now and in the future.

But if we think about end-of-life plans and find ourselves disengaging from life, something’s wrong. We may be overly preoccupied with dark fears or sadness about death. In these bleak moments, we’re likely isolating ourselves from loved ones or others who can help us with the process.

End-of-life planning is a process that involves your loved ones. They need to know what decisions you’d like them to make if you can no longer speak for yourself. So, no one should go through the process alone.

Alright, I’m convinced. But how do I start end-of-life planning?

We can sum up the process into three steps.

- Complete your advance directives and make them legal.

- Post them openly in your home and give them to loved ones and your doctors.

- Talk about them with your health proxy, your loved ones, and your medical team.

What are advance directives?

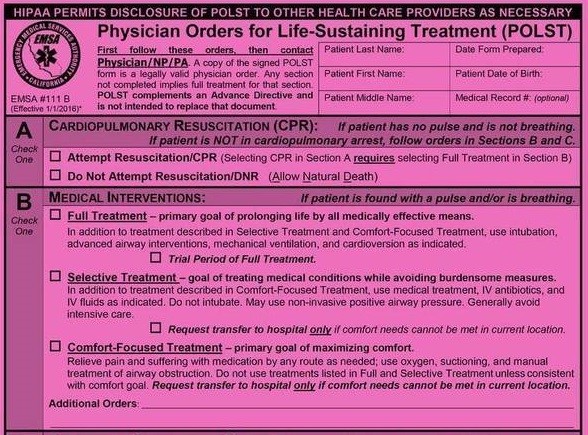

Advance directives are the documents that make your choices legal. These documents include a living will and a power of attorney for health care.

A living will describe the type of end-of-life medical care you want in certain situations. It directs and guides your chosen decision-maker and medical team to make decisions for you. Your instructions in the living will, can be as creative as you want.

These directives are kind to your family. Instead of agonizing over medical decisions without your input, they can more confidently and peacefully make the right decisions for you.

A power of attorney for health care legally names the person you want to make your healthcare decisions when you cannot. This decision-maker is also called a health proxy. They become your voice when you can’t speak for yourself.

Your advance directives are yours to define and only become active when you are suddenly, by illness or injury, unable to make your own decisions.

Where do I get the paperwork?

For a paper copy, start with your doctor’s office or the closest hospital. They often stock advance care paperwork that meets your state’s standards.

Not surprising, there are many online options to suit your needs. These sites are a great place to start because they help you think about your end-of-life wishes and answer a lot of questions. Some are free, and some cost as little as five dollars. You can get trustworthy free documents at CaringInfo, MyDirectives, and Prepare for Your Care.

But these details only scratch the surface. Planning can feel overwhelming, but don’t let that stop you. Push through for the sake of your life now. For the sake of your loved ones.

If it gets hard to talk about or feels too complicated, consider talking with a local palliative care social worker or chaplain. End-of-life doulas also help people safely talk about death and advance care plans.

Remember, death planning is about life. Let these words from Dr. Fehon guide you. “What does living well mean now [to you]? Whatever your circumstances, whether you’re healthy or not, [end-of-life planning] is a recognition of what’s important and to try to live in a way that is in alignment with your values, your priorities authentically.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!