Nearly nine years ago, I received a call from my stepmother summoning me to my grandmother’s house. At 92 years old, my Oma had lost most of her sight and hearing, and with it the joy she took in reading and listening to music. She spent most of her time in a wheelchair because small strokes had left her prone to falling, and she was never comfortable in bed. Now she had told her caregiver that she was “ready to die,” and our family believed she meant it.

I made it to my grandmother in time to spend an entire day at her bedside, along with other members of our family. We told her she was free to go, and she quietly slipped away that night. It was, I thought, a good death. But beyond that experience, I haven’t had much insight into what it would look like to make peace with the end of one’s life.

A recent study published in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, which gathered data from terminal patients, family members and health care providers, aims to clarify what a good death looks like. The literature review identifies 11 core themes associated with dying well, culled from 36 studies:

- Having control over the specific dying process

- Pain-free status

- Engagement with religion or spirituality

- Experiencing emotional well-being

- Having a sense of life completion or legacy

- Having a choice in treatment preferences

- Experiencing dignity in the dying process

- Having family present and saying goodbye

- Quality of life during the dying process

- A good relationship with health care providers

- A miscellaneous “other” category (cultural specifics, having pets nearby, health care costs, etc.)

In laying out the factors that tend to be associated with a peaceful dying process, this research has the potential to help us better prepare for the deaths of our loved ones—and for our own.

Choosing the way we die

Americans don’t like to talk about death. But having tough conversations about end-of-life care well in advance can help dying people cope later on, according to Emily Meier, lead author of the study and a psychologist who worked in palliative care at the University of California San Diego’s Morres Cancer Center. Her research suggests that people who put their wishes in writing and talk to their loved ones about how they want to die can retain some sense of agency in the face of the inevitable, and even find meaning in the dying process.

Natasha Billawala, a writer in Los Angeles, had many conversations with her mother before she passed away from complications of the neurodegenerative disease ALS (amytropic lateral sclerosis) in December 2015. Both of her parents had put their advanced directives into writing years before their deaths, noting procedures they did and didn’t want and what kinds of decisions their children could make on their behalf. “When the end came it was immensely helpful to know what she wanted,” Billawala says.

When asked if her mother had a “good death,” according to the UCSD study’s criteria, Billawalla says, “Yes and no. It’s complicated because she didn’t want to go. Because she lost the ability to swallow, the opportunity to make the last decision was taken from her.” Her mother might have been able to make more choices about how she died if her loss of functions had not hastened her demise. And yet Billawalla calls witnessing her mother’s death “a gift,” because “there was so much love and a focus on her that was beautiful, that I can carry with me forever.”

Pain-free status

Dying can take a long time—which sometimes means that patients opt for pain medication or removing life-support systems in order to ease suffering. Billawala’s mother spent her final days on morphine to keep her comfortable. My Oma, too, had opiate pain relief for chronic pain.

Her death wasn’t exactly easy. At the end of her life, her lungs were working hard, her limbs twitching, her eyes rolling behind lids like an active dreamer. But I do think it’s safe to say that she was as comfortable as she could possibly be—far more so than if she’d been rushed to the hospital and hooked up to machines. It’s no surprise that many people, at the end, eschew interventions and simply wish to go in peace.

Emotional well-being

Author and physician Atul Gwande summarizes well-being as “the reasons one wishes to be alive” in his recent book Being Mortal. This may involve simple pleasures like going to the symphony, taking vigorous hikes or reading books He adds: “Whenever serious sickness or injury strikes and your body or mind breaks down … What are the trade-offs you are willing to make and not willing to make?”

Kriss Kevorkian, an expert in grief, death and dying, encourages those she educates to write advance directives with the following question in mind: “What do you want your quality of life to be?”

The hospital setting alone can create anxiety or negative feelings in an ill or dying person, so Kevorkian suggests family members try to create a familiar ambience through music, favorite scents, or conversation, among other options, or consider whether it’s better to bring the dying person home instead. Billawalla says that the most important thing to her mother was to have her children with her at the end. For many dying people, having family around can provide a sense of peace.

Opening up about death and dying

People who openly talk about death when they are in good health have a greater chance of facing their own deaths with equanimity. To that end, Meier is a fan of death cafés, which have sprung up around the nation. These informal discussion groups aim to help people get more comfortable talking about dying, normalizing such discussions over tea or cake. It’s a platform where people can chat about everything from the afterlife (or lack thereof) to cremation to mourning rituals.

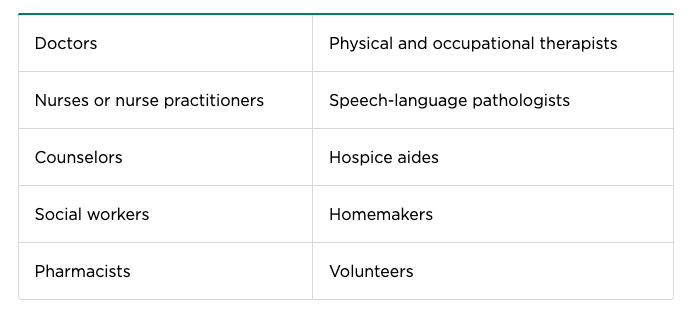

Doctors and nurses must also confront their own resistance to openly discussing death, according to Dilip Jeste, a coauthor of the study and geriatric psychiatrist with the University of California San Diego Stein Institute for Research on Aging. “As physicians we are taught to think about how to prolong life,” he says. That’s why death becomes [seen as] a failure on our part.” While doctors overwhelmingly believe in the importance of end-of-life conversations, a recent US poll found that nearly half (46%) of doctors and specialists feel unsure about how to broach the subject with their own patients. Perhaps, in coming to a better understanding of what a good death looks like, both doctors and laypeople will be better prepared to help people through this final, natural transition.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!