By Tim Lawrence

I’m listening to a man tell a story. A woman he knows was in a devastating car accident, and now she lives in a state of near-permanent pain; a paraplegic, many of her hopes stolen.

I’ve heard it a million times before, but it never stops shocking me: He tells her that he thinks the tragedy had led to positive changes in her life. He utters the words that are nothing less than emotional, spiritual, and psychological violence:

“Everything happens for a reason.”

He tells her that this was something that had to happen in order for her to grow. But that’s the kind of bullshit that destroys lives. And it’s categorically untrue.

After all these years working with people in pain as an advisor and adversity strategist, it still amazes me that these myths persist despite the fact that they’re nothing more than platitudes cloaked as sophistication. And worst of all, they keep us from doing the one thing we must do when our lives are turned upside down: grieve.

Here’s the reality: As my mentor Megan Devine has so beautifully said: ‘Some things in life cannot be fixed. They can only be carried.’

Grief is brutally painful. Grief does not only occur when someone dies. When relationships fall apart, you grieve. When opportunities are shattered, you grieve. When illnesses wreck you, you grieve.

Losing a child cannot be fixed. Being diagnosed with a debilitating illness cannot be fixed. Facing the betrayal of your closest confidante cannot be fixed. These things can only be carried.

Let me be clear: If you’ve faced a tragedy and someone tells you in any way that your tragedy was meant to be, happened for a reason, will make you a better person, or that taking responsibility for it will fix it, you have every right to remove them from your life.

Yes, devastation can lead to growth, but it often doesn’t. It often destroys lives — in part because we’ve replaced grieving with advice. With platitudes.

I now live an extraordinary life. I’ve been deeply blessed by the opportunities I’ve had and the radically unconventional life I’ve built for myself.

But loss has not in and of itself made me a better person. In fact, in some ways it’s hardened me.

While loss has made me acutely aware and empathetic of the pains of others, it’s also made me more inclined to hide. I have a more cynical view of human nature and a greater impatience with people who are unfamiliar with what loss does to people.

Above all, I’ve been left with a pervasive survivor’s guilt that has haunted me all my life. In short, my pain has never gone away, I’ve just learned to channel it into my work with others. But to say that my losses somehow had to happen in order for my gifts to grow would be to trample on the memories of all those I lost too young, all those who suffered needlessly, and all those who faced the same trials I did but who did not make it.

I’m simply not going to do that. I’m not going to assume that God ordained me for life instead of all the others, just so that I could do what I do now. And I’m certainly not going to pretend that I’ve made it simply because I was strong enough, that I became “successful” because I “took responsibility.”

I think people tell others to take responsibility when they don’t want to understand.

Understanding is harder than posturing. Telling someone to “take responsibility” for their loss is a form of benevolent masturbation. It’s the inverse of inspirational porn: It’s sanctimonious porn.

Personal responsibility implies that there’s something to take responsibility for. You don’t take responsibility for being raped or losing your child. You take responsibility for how you choose to live in the wake of the horrors that confront you, but you don’t choose whether you grieve. We’re not that smart or powerful. When hell visits us, we don’t get to escape grieving.

This is why all the platitudes and focus on “fixes” are so dangerous: by unleashing them on those we claim to love, we deny them the right to grieve.

In so doing, we deny them the right to be human. We steal a bit of their freedom precisely when they’re standing at the intersection of their greatest fragility and despair.

The irony is that the only thing that even can be “responsible” amid loss is grieving.

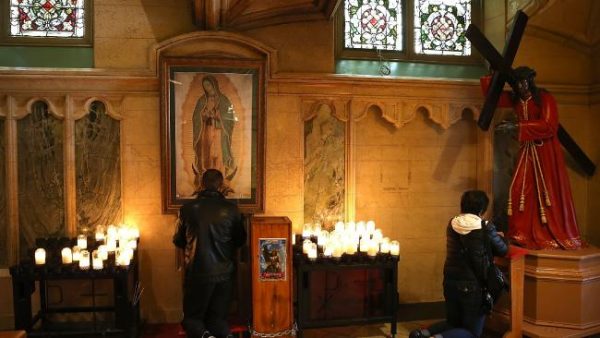

I’ve grieved many times in my life. I’ve been overwhelmed with shame so strong it nearly killed me. The ones who helped — the only ones who helped — were those who were simply there.

I am here — I have lived — because they chose to love me. They loved me in their silence, in their willingness to suffer with me and alongside me. They loved me in their desire to be as uncomfortable, as destroyed, as I was, if only for a week, an hour, even just a few minutes. Most people have no idea how utterly powerful this is.

Healing and transformation can occur. But not if you’re not allowed to grieve. Because grief itself is not an obstacle.

The obstacles come later. The choices as to how to live, how to carry what we have lost, how to weave a new mosaic for ourselves? Those come in the wake of grief.

Yet our culture treats grief like a problem to be solved or an illness to be healed. We’ve done everything we can to avoid, ignore, or transform grief. So that now, when you’re faced with tragedy, you usually find that you’re no longer surrounded by people — you’re surrounded by platitudes.

So what do we offer instead of “everything happens for a reason”?

The last thing a person devastated by grief needs is advice. Their world has been shattered. Inviting someone — anyone — into their world is an act of great risk. To try to fix, rationalize, or wash away their pain only deepens their terror.

Instead, the most powerful thing you can do is acknowledge. To literally say the words:

I acknowledge your pain. I’m here with you.

Note that I said with you, not for you. For implies that you’re going to do something. That’s not for you to enact. But to stand with your loved one, to suffer with them, to do everything but something is incredibly powerful.

There is no greater act for others than acknowledgment.

And that requires no training, no special skills — just the willingness to be present and to stay present, as long as is necessary.

Be there. Only be there. Don’t leave when you feel uncomfortable or when you feel like you’re not doing anything. In fact, it’s when you feel uncomfortable and like you’re not doing anything that you must stay.

Because it’s in those places — in the shadows of horror we rarely allow ourselves to enter — where the beginnings of healing are found. This healing is found when we have others who are willing to enter that space alongside us. Every grieving person on earth needs these people.

I beg you, be one of these people.

You are more needed than you will ever know. And when you find yourself in need of those people, find them. I guarantee they are there.

Everyone else can go.

Complete Article HERE!