There are a number of documents that unwed partners can put in place if they want to make sure each is protected if the other person dies.

Maggie Kirchhoff and her partner of 13 years, Matt, have no intention of ever getting married.

They also know it means they won’t get the automatic rights and protections that legally wed spouses get — particularly when it comes to death.

“A lot of spousal rights are inherent with a marriage certificate,” said Kirchhoff, a certified financial planner with Business & Personal Finance in Denver. “For unmarried couples, though, you have to make a concerted effort to cover all your bases.”

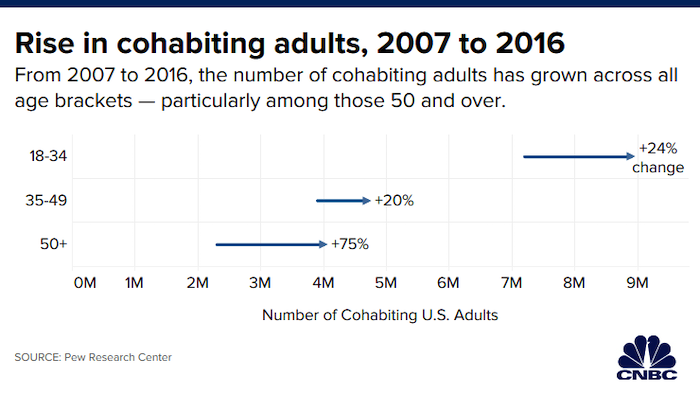

The number of unmarried couples who live together reached 18 million in 2016, a 29% jump from 14 million in 2007, according to the Pew Research Center. Among adults age 50 and older, however, the increase was 75%: About 4 million were cohabiting in 2016, up from 2.3 million in 2007.

Although the arrangement has gained broad societal acceptance, according to a separate Pew Research report, such couples still face some key differences from their married counterparts.

For example, filing a federal tax return as a couple is off the table. If your employer happens to extend health insurance to your partner, the amount your company contributes is taxable to you (vs. being tax-free for a spouse).

And, as mentioned, end-of-life considerations need some attention.

About five years into their relationship, Kirchhoff and her partner — who also is a CFP — signed a variety of documents that will dictate what happens if one of them either becomes incapacitated or dies.

In other words, they created an estate plan.

The basics

Remember, “estate” simply refers to everything you own — i.e., financial accounts, real estate and your belongings.

Experts say that creating a plan for what happens to your estate — regardless of how meager or massive your assets — is key for unmarried couples who want their commitment to each other protected in the event of death.

“If I’m married and die without an estate plan, it would be a mess, but the general default would be that everything ends up with my spouse,” said Nick Rosenbauer, an estate planning attorney and founder of the Rosenbauer Law Office in West Chester, Ohio.

“But if I’m not married, the default wouldn’t be my partner,” Rosenbauer said. “It might be my kids or my parents or siblings, but my partner who isn’t legally my spouse would be out of the picture.”

If you die without a will — called dying intestate — the courts in your state will decide who gets what. That process is public and often messy if would-be heirs have competing priorities and conflicting notions of what is rightfully theirs.

That said, a will alone won’t necessarily cover all your bases.

Retirement accounts

If you want to make sure your tax-advantaged retirement accounts — i.e., Roth and traditional individual retirement accounts, 401(k) plans and the like — end up with your partner, make sure that person is the named beneficiary on those accounts.

Even if you have a will that states otherwise, whoever is listed as the beneficiaries on those accounts will get the money. Same goes for insurance policies and annuities.

If no beneficiary is listed, where the money goes depends partly on the retirement plan agreement and on state law. Typically, though, those retirement assets would end up being included in your assets that are subject to probate.

That’s the process of the court validating your will (if there is one) after your death. If there is no will, the court will pass everything on according to state law — which typically means assets will go to the closest living family member who, again, is not going to be your unmarried partner.

Probate is also when creditors can come after your estate for amounts owed and other would-be heirs can contest your will.

Bank and brokerage accounts

If both of your names are on checking, savings or investment accounts, there’s no worry about either of you being able to access them if one of you were to die. The same can’t be said for those with only one person’s name on it.

For any account with only your name on it, contact your bank to find out what form needs to be filled out so the money is left directly to your partner.

“You’d either want to add what’s called a transfer-on-death or payable-on-death designation,” Kirchhoff said.

Again, without those designations, the assets would end up in probate and distributed either in accordance with the will or state laws.

The family house

Regardless of whether you split the mortgage — or whose name is on that loan — the person named on the deed is the owner.

“If the house in one person’s name, it won’t automatically pass to the partner,” Kirchhoff said. “It would become part of the probate estate.”

One option is to make sure both of you are named as joint owners on the deed, “with rights of survivorship.” In that case, generally speaking, you each equally own the house and are entitled to assume full ownership upon the death of the other.

However, there could be other factors to consider before adding a partner’s name to an existing deed, including the cost, tax implications or protection from potential creditors. In other words, you might want to consult with a professional before making the move.

Another option is to leave the house to your partner in your will. Remember, though, any asset passing through the bounds of your will is subject to probate and the potential snags that can come with that.

Consider a trust

Depending on the complexity of your financial situation and the type of assets you own, a trust could be one way to ensure that your partner ends up with what you want them to without any of it being subject to probate.

However, there are other considerations that should factor into whether you create one or not, including whether it would make sense tax-wise, and if the cost (which can be several thousand dollars) is worth it.

Communication

It also is probably worth letting any pertinent family members — i.e., adult children, parents or siblings — know the general intentions included in your estate plan.

While you don’t necessarily need to go into dollar amounts, managing expectations can help avoid discord between your partner and any other family members.

“I always recommend that clients discuss these plans with family to avoid hurt feelings or missed expectations,” said Eric Walters, a CFP and managing partner and founder of SilverCrest Wealth Planning in Greenwood Village, Colorado.

Other considerations

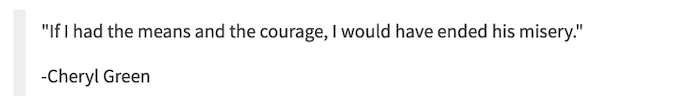

Generally speaking, your partner has no legal say in your medical treatment if you end up in a situation when you cannot make decisions yourself.

If you want to give the person that right, you can give them a durable power of attorney over health care. That will let your partner — or whomever you name — make important health-care decisions if you’re unable to.

This is separate from a living will, which states your wishes if you are on life support or suffer from a terminal condition. This helps guide your proxy’s decision-making. And if you have no one named, medical personnel must follow your wishes in that document.

Additionally, you might want to give your partner durable power of attorney for your finances. This would allow them to handle your money, including accessing your accounts as necessary, if you cannot.

And, Kirchhoff said, don’t forget to put contingent decision-makers on those documents.

“If there’s a likelihood that you and your partner are going to be traveling together, and something were to happen to both of you, then who’s in charge?” she said.

Similarly, if you and your partner have dependents, make sure you designate a guardian for them in your will. Otherwise, that decision will be left to the courts.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!