By GARRY OVERBEY

A 94-year-old Venice man allegedly shot and killed his wife, who suffered from dementia. He then tried to turn the gun on himself, authorities said, but the weapon jammed. He told the 911 dispatcher, “I’ve had a death in the family.”

Cheryl Green, 73, lost her husband of 54 years in July after a long struggle with Lewy body dementia.

When Green read about the arrest of Wayne S. Juhlin — currently the oldest inmate at the Sarasota County Jail, charged with first-degree murder — she felt sympathy for him — and guilt, for her husband.

“Unless you’ve walked in his shoes, you don’t know what’s going on,” she said. “He (Juhlin) probably saw something in her condition, that killing her was a mercy.”

The would-be murder/suicide made her think of her husband, and the horror of his final days in a Lake Placid nursing home.

“If I had the means and the courage, I would have ended his misery,” Green said.

She contacted the Sun following Juhlin’s arrest, objecting to the narrative put forth by authorities that help for caregivers is readily available but ignored.

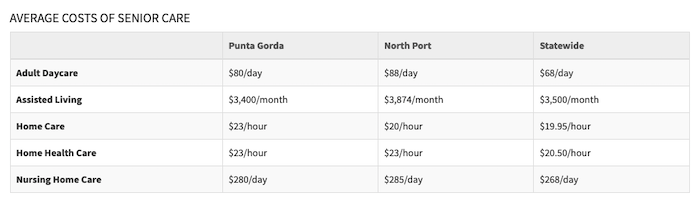

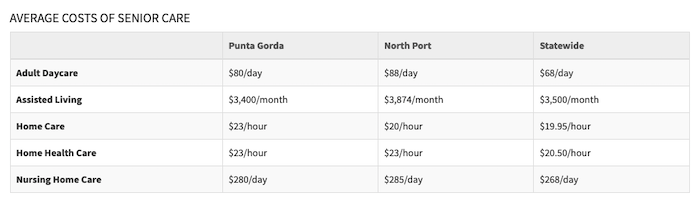

“It sounded as if there were many options open to the man and he just didn’t know they were there. The options are few for individuals who don’t have a lot of money,” she said.

Had her husband been accepted into a long-term care facility, she said, she would have depleted their savings in two months.

A former Washington state employee with a degree in social work, Green said she’s not naive about Medicare and Medicaid and how easily people can slip through the cracks of a bureaucracy. But she was stunned to find herself marginalized in Florida’s elder care system.

“If you’re indigent and you need long-term care, you can get Medicaid,” she said. “But if you’re in the middle — if you’re not wealthy enough to afford $3,000 to $5,000 a month (for nursing care) — you’re stuck.”

Through the looking glass

Cheryl and Drew Green both grew up in upstate New York. High school sweethearts, they met while working in the same grocery store and married while still in their teens.

They moved to Seattle, where she got her master’s degree in special vocational education, he opened his own business as an electrician, and they raised their two children. She worked for the state, running and developing programs for people with developmental disabilities and mental health issues.

Drew was extremely handy and could do almost anything that needed doing around the house.

“He was an excellent craftsman,” Green said. “People liked him because he was so good at what he did.”

Around his mid-50s, things changed.

“He started making mistakes at work,” Green said. “He would say, ‘I don’t know why, but I can’t figure things out anymore.’”

The man who had once built her a backyard gazebo was now forgetting things and had trouble with basic tasks.

Doctors told them he had dementia, but it would be years before one finally diagnosed him with a specific type: Lewy body dementia. LBD is a progressive form of the disease, with visual hallucinations, that affects thinking, behavior, mood and movement. Life expectancy is usually five to seven years.

Drew couldn’t work and his business folded. Green quit her job to care for him. Seattle was too expensive under those circumstances, so she looked for a cheaper place to live. In 2010, they moved to Burnt Store Lakes in Punta Gorda.

They lived off their savings and took early Social Security benefits. As his health declined, they were relieved when he qualified for Medicare.

“He was living in an alternate reality,” she said. “He had delusions and thought he had to act on them.”

For instance, Drew once thought he could go upstairs by walking through a mirror.

His condition steadily worsened over the years.

“He still had a sense of humor. He stayed kind,” she said. “But he became really delusional and started lashing out at people.”

Drew would sometimes stay up and wander the house for three or four days at a time. He would walk into sliding glass doors.

“I was under the delusion that I could take care of him,” she said.

Green, who had been diagnosed with lupus in the last year after struggling with fatigue her whole life, was exhausted and finally reached out for help. Earlier this year, she contacted Charlotte County’s Senior Services. They agreed to send someone to help for four hours twice a week to provide respite care — giving the caregiver a break for a few hours and helping with household chores. But when the worker arrived, Green was shocked to learn she didn’t speak English. Green was handed a cell phone and told to talk to a supervisor, who would translate Green’s instructions. A second worker spoke some English, but she mainly sat and did puzzles while Drew watched.

The county’s Senior Services cannot discuss details of a specific case because of privacy, but there are limitations on help that can be provided.

“Vendors do have difficulties providing services in more remote areas of the county, weekends and evening service, and we have no vendor willing to handle heavier chore tasks,” said Deedra Dowling, manager of Charlotte County Human Services/Senior Division. “We depend on the subcontracted vendors to provide the staff for service provision and we do monitor for contract compliance. … We have had clients who have tried every worker, every agency, and finally left with no service provision as they could not be satisfied. While this scenario is extremely rare, it has happened a few times over the years. Overnight services have always been extremely difficult to staff for a variety of reasons.”

Dowling added she wishes there were “many more resources.”

Green said she needed someone to come three nights a week, and someone on call at night.

She started sleeping on the couch so she could keep an eye on the doors to make sure he didn’t leave the house.

“I didn’t understand what I needed. I thought, I’ll keep him until I can’t keep him home anymore.”

Resources were few. Her children, who live out of state, helped when they could. Neighbors helped, but Drew’s aggression scared them.

“It’s difficult to ask anybody to help restrain someone in the middle of the night.”

Reality check

In May, Drew escaped through a window. Green searched the neighborhood and found him wandering the streets in his boxer shorts. The next night, he got out again. This time, she found him unconscious in the bushes near the alligator-infested lake behind their home.

She brought him to Fawcett Memorial Hospital May 19. He was placed under observation, but Medicare wouldn’t pay until he was actually admitted, which happened once he began having heart issues and his blood pressure shot up.

His decline accelerated. “He started punching people,” Green said. “He was scary aggressive.”

At Fawcett, she credits one doctor with giving her a reality check on what she knew were her husband’s last days: “He said, ‘This isn’t a fairy tale. Grandpa isn’t going to come home and be surrounded by loving grandchildren.’ He said he’ll be ranting and raving and lashing out at people.”

One night in the hospital, to keep him from jumping out of his bed, Green wrapped him in a bed sheet and held it tight.

He was beyond being helped at home. A doctor said he would need three people caring for him around the clock.

“Obviously, he was lots and lots of work wherever he went.”

She tried to get him into Tidewell Hospice, but was turned down. She said she wasn’t given a reason, only that he “didn’t meet the criteria.”

“I knew he was dying,” she said.

A hospital social worker started looking for a nursing home, but no one local would take him, Green said, “because he was aggressive and had Lewy body, and they didn’t have the experience or the staff to deal with him.”

Only two facilities in the state would take him. Online reviews for the one in Clearwater were so bad it was unthinkable, so she went with a facility in Lake Placid.

“I hoped maybe he could have some rehabilitation, maybe learn to feed himself again.”

Fawcett insisted he be transported to Lake Placid by ambulance, a $3,000 trip the hospital agreed to cover.

‘The old person’s friend’

The Lake Placid facility turned out to be worse than she could have imagined.

“The place was dirty, the staff overworked and the administration was less than helpful.”

Drew’s conditioned worsened.

“He could not feed himself or use the bathroom,” Green said. “He cried when he saw me. He was wet, dirty and being fed food he would never eat in his former life. He was frightened and tried to keep the staff away from him. He was usually put in an old wheelchair missing half its parts and was slumped to the side.”

After 20 days, the facility notified her he would be taken off Medicare because he wasn’t making progress. They would let him continue to stay there for $260 a day. Had Green agreed, “I would go through any money I had left very quickly,” to keep him in a place where “I would not keep my dog.”

“I wanted someplace stable where I could visit him, but that was not available to me at all,” she said. “I looked every day for a new place. He was terrified and I was miserable.”

Suffering from infections, pneumonia and near-continuous seizures, Drew was taken to the emergency room. From there, he was finally accepted to a hospice in Clermont, near Orlando. Green noted someone telling her pneumonia was called “the old person’s friend” — “because it takes them away when they have other diseases.”

“It was a wonderful place to be,” she said of hospice.

She was able to be with him that night. The next morning, July 16, a nurse’s aide told her he had died.

A better ending

Three months later, Drew’s last days haunt her.

“What an awful way to die — thinking you’re not safe, that you’re being attacked all the time, no help from anybody, and the nursing home didn’t want him anymore.

“To have him in that place, to see him crying and scared,” she said, shaking her head. “I’ll never get over the guilt.”

She adds: “I shouldn’t have lived in a delusional state that I could take care of him.”

If he could have gotten into a hospice earlier, she said, “his life would have had a better ending.”

Her thoughts roll back to Juhlin and others like him who took action to end a loved one’s suffering.

“I don’t think I could kill anybody, especially someone I loved. But I wish I could have ended his misery.

“It’s horrible when the person you love most, you think they’d be better off dying. My last three dogs got so sick I had to put them down. I loved those dogs. I didn’t murder them.

“I wouldn’t shoot anybody, but I might have given him too many sleeping pills.”

Green said she visits online forums for people with loved ones suffering from Lewy body dementia. But she is reluctant to participate.

“I don’t want to tell my story because I don’t want them to know how bad it’s going to be.”

She wants to be an advocate for raising awareness about the condition, and offers advice for those in similar situations.

“Don’t think that anyone is going to automatically be there to help you.”

She recommends getting an elder care attorney once it becomes clear a loved one is going to require long-term care.

“Sit down and talk about Medicare and Medicaid options, and whether you can keep your house after your loved one passes away.”

Green still owes a little money on their house, and she’s confident she can keep up with home repairs without having to take out a loan.

Nine years of Medicare “doughnut hole” expenses for Drew’s medications, as well as retiring early, ate up their savings.

Still, she’s able to get by on Social Security and her pension from Washington. Plus, she says with a little chuckle, Social Security gives her a widow’s pension — $37.91 a month.

She’s adjusting to life without her husband.

“I had a man who could do everything,” she said. “Now I’m figuring out how to do everything.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!