A lot of Baby Boomers have died recently. Garry Shandling. David Bowie. Glenn Frey. And now, Patty Duke.

I was connected to her in a very personal way. When we were preteens, my best friend (also my cousin), and I used to sit in front of the TV in our sponge curlers and Lanz nightgowns, fantasizing about what it would be like to be Patty, always getting into trouble (but having fun) in high school. We loved, too, Cathy, her identical perfectly behaved but boring cousin from Scotland (with that adorable accent). I was always Cathy.

This is what high school would be like, falling in love with our French teachers, switching places to fool teachers, Cathy getting a flu shot when they thought she was Patty. And that flip haircut! Kind of like us.

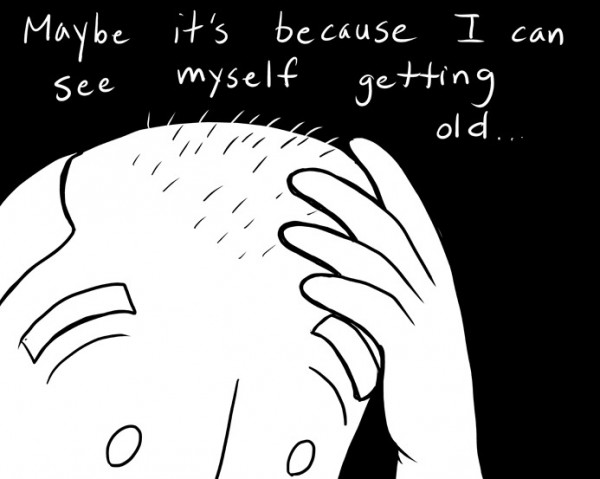

Then came the drugs and divorces, and bipolar disorder, and no more sweet Patty Lane. The fairy tale ended. For a long time, her life was in decline. Just like a lot of us.

Something broke inside when I heard of her death. I’ve had friends die — one, at 37 — but it’s getting closer and closer.

My husband has started collecting Social Security and now, Medicare.

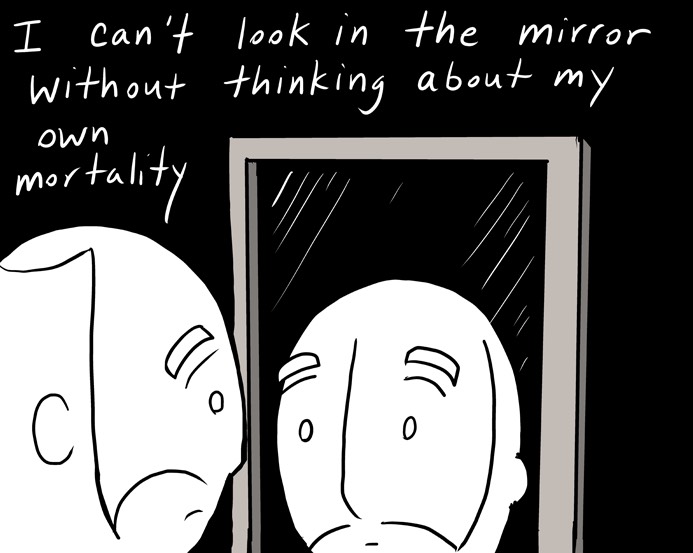

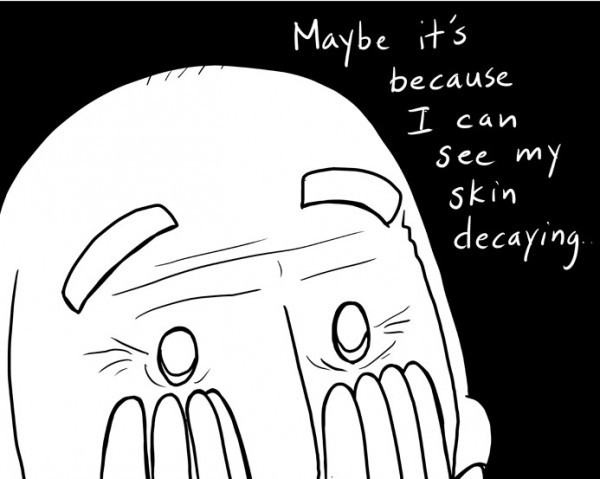

You know somewhere, in the back of your head, that you will die someday. I, more than most, was exposed to it early, diagnosed twice with cancer.

I suppose it’s all coming home to me because my husband is facing surgery. Yes, it’s minor. But it suddenly got him talking about wills and annuities and trusts and who to call (we’ve always kept our finances separate but he’s afraid he’s going to die and wants to make sure my son and I are taken care of). I guess be grateful for small things!

And then I realized, he’s going to die. Maybe not before me, but he will. We just celebrated our 22nd anniversary (actually been together 33 years and I want credit for it all!), and we’ve had our problems through the years. But I suddenly realized I loved him. What will life be like without him? We’ve been together more than half my lifetime. I don’t know what I will do if he is no longer there.

OK, so I’ll get the TV back (no more Bill O’Reilly) and I won’t have to pick up his ski coat off the floor, where he throws it when he comes home. And I won’t have to listen to any more diatribes about how Bernie Sanders will drive us to taxation hell.

You know this day will eventually come. But it just all seems so soon now.

Research has shown that 52 percent of Americans over 65 will not have enough money to maintain their style of living when they retire — because we haven’t wanted to think about dying. We haven’t made plans, so afraid of our impending mortality. Didn’t we all think we’d live forever? We were the Baby Boomers, after all!

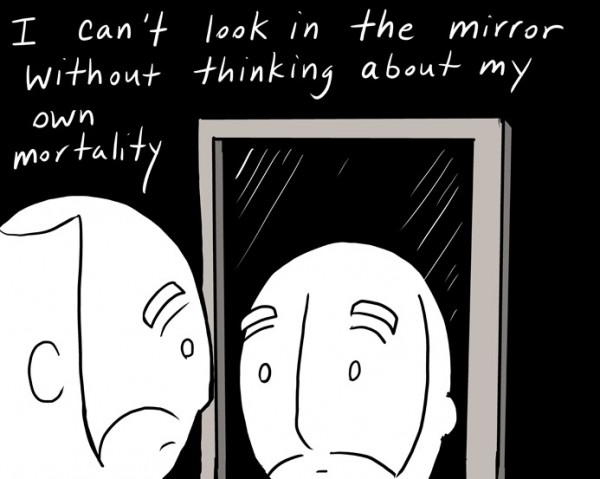

As I said, I had an early preview so maybe it’s easier for me. But I still see my husband as the tall, skinny tennis star walking off the court with his trophy (and if I’m honest, me, too, in my short shorts and halter top).

He’s still athletic but his hernia has turned him into an old man overnight. Because of the pain, he’s had a hard time walking (and forget about getting in and out of the car!). It hasn’t stopped him from working at the two dental clinics he helps out at in New York, or even from using the elliptical and stationary bike at home.

But he still walks very, very slowly and it’s like getting a taste of the future.

Hopefully, the surgery will reverse that. But there’s no getting around it. We’re getting old.

I’m hoping next week he’ll be back to complaining that the paper towels are running out and returning to his endless “Camp Larry” Sundays, where he exercises for four hours at a stretch.

But I’m starting to think it’s the beginning of the end. Or maybe, it’s just the end of the beginning.

Complete Article HERE!