Searching for death-positive books in a death-phobic culture

By John MacNeill Miller

Not long after they die, even the best novelists start to stink.

Maybe that explains why we have so few great stories about what happens after we die. The novelistic tradition is rich with deathbed scenes and moving explorations of grief, but serious fiction about mortality inevitably stops at death’s door. Remarking this pattern in 1927, E. M. Forster blamed novelists’ hesitation to write about the dead on the dead themselves. “[D]eath is coming,” he admits in his influential treatise Aspects of the Novel, but we cannot write about it in any convincing way because — as the saying goes — dead men tell no tales. “Our final experience, like our first, is conjectural,” he concludes. “We move between two darknesses.”

Forster’s reasoning seems sound enough. If we want to move from a pathologically death-phobic culture to a more well-adjusted one, however, we need to rethink our cultural tradition of giving death the silent treatment. That is the sentiment underlying the death-positive movement, a loose collective of artists, writers, academics, and funeral industry professionals agitating for more open conversations about dying. As the mortician and author Caitlin Doughty explains in her bestselling memoir Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, “A culture that denies death is a barrier to achieving a good death.”

At the very minimum, our culture of death denial creates a population unprepared for the inevitability of death, one in which every dying individual burdens family and friends with painful healthcare decisions, legal battles, and property disputes that could have been avoided with a little forethought. At its worst, death denial promotes a youth- and health-obsessed society whose inability to address death fuels overwhelming feelings of anxiety, depression, and powerlessness in the face of illness and age.

As Doughty — perhaps the most prominent figure of the death-positive movement — admits at the end of her memoir, “Overcoming our fears and wild misconceptions about death will be no small task.” She looks to the medieval spiritual guidebooks known as Ars Moriendi (Latin for “The Art of Dying”) for inspiration. We need to re-teach ourselves how to die, she argues — a process that begins with an open admission of our thoughts, fears, and beliefs about death. Treating death as a hushed affair will only make matters worse. “Let us instead reclaim our mortality,” she concludes, “writing our own Ars Moriendi for the modern world with bold, fearless strokes.”

We need to re-teach ourselves how to die—a process that begins with an open admission of our thoughts, fears, and beliefs about death.

The spate of books on death and dying published in the past two years suggests that many writers have taken Doughty’s words to heart. These works run the gamut from a grisly history of Victorian surgery to a study of American hauntings, and they include the lavishly illustrated essay collection Death: A Graveside Companion and Doughty’s own From Here to Eternity, a comparative analysis of death practices from around the world. For a group interested in the art of dying, however, the death-positive movement is strikingly uninterested in art of the literary variety: in its concentration on turning a spotlight on the facts of death, the death-positive movement has not yet explored the relationship between death and fiction.

If we want to reclaim the good death as part of the good life, we need to consider how we incorporate death in the stories we tell about ourselves. When we tacitly treat death as The End of every individual’s story, we only increase a collective sense of death’s unspeakability. What lies beyond the grave seems unthinkable in part because it remains unimaginable. Yet if Forster is right, it seems we are at an impasse: given the silence of the tomb, how can storytellers represent death as something other than a final stop?

If we want to reclaim the good death as part of the good life, we need to consider how we incorporate death in the stories we tell about ourselves.

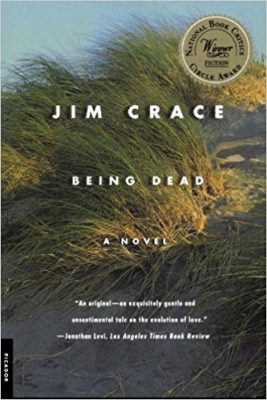

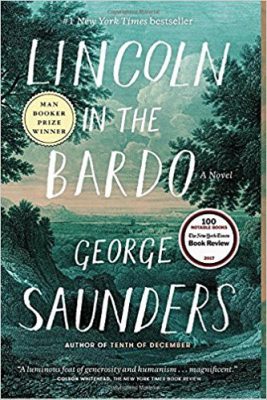

Two award-winning attempts at writing the afterlife — one from 1999 and one from 2017 — offer two different approaches to answering the question. Taken together, Being Dead and Lincoln in the Bardo show that it is possible to tell smart, powerful stories that represent death as something other than a stunningly final silence. They also show that the precise forms such stories take have profound implications for the ways we value life, and the ways we understand the place of death within it.

The very title of Jim Crace’s Being Dead promises tantalizing access to that posthumous experience that Forster believed to be off limits. Yet there is a bit of a bait-and-switch here: Crace’s novel leaves little room for speculative adventures into otherworldly existence. Being Dead is a postmortem story in an almost clinical sense. It tells the love story of Joseph and Celice, two young scientists who get married, raise a daughter, and settle into late life together. But if this is love, it is love under the knife: Crace’s scalpel-sharp realism cuts to the heart of desire with a kind of ruthless detachment unmatched since Flaubert.

The very title of Jim Crace’s Being Dead promises tantalizing access to that posthumous experience that Forster believed to be off limits. Yet there is a bit of a bait-and-switch here: Crace’s novel leaves little room for speculative adventures into otherworldly existence. Being Dead is a postmortem story in an almost clinical sense. It tells the love story of Joseph and Celice, two young scientists who get married, raise a daughter, and settle into late life together. But if this is love, it is love under the knife: Crace’s scalpel-sharp realism cuts to the heart of desire with a kind of ruthless detachment unmatched since Flaubert.

The result is less the touching portrait of a couple than an autopsy of their relationship — and that is only appropriate, because the novel opens with their murder. Joseph and Celice die of a kind of misplaced nostalgia. They have unnecessarily returned, in late middle age, to the sand dunes where they first conducted research together and gave in to youthful passion. The explicit purpose of their trip is to visit the dunes one last time before the place is destroyed by encroaching development. But the couple’s desire, here and elsewhere, is divided: Celice wants to make peace with the death of a friend that occurred exactly as she and Joseph first fell for each other, while Joseph only wants to reenact their tryst on the dunes.

Joseph’s “plan” is utterly transparent to Celice, who indulges him out of pity rather than affection. Their actual encounter ends in embarrassment; Joseph finishes before it starts. They resolve to try again after lunch but never get that chance. A furious stranger stumbles across the defenseless, naked pair as they sit together, and he bashes their skulls in with a rock.

Because the couple has already died as the story begins, the novel proceeds by alternating backward glances with real-time narration, interspersing Joseph and Cecile’s love story with the lurid details of their bodily decomposition. The result is touching and gruesome by turns, but not necessarily in the ways you would expect: the descriptions of decay offer welcome relief from the cringeworthy details of the awkward, lopsided desires that brought the couple together. The novel seems, in fact, to struggle with its own inevitable slide toward the romanticization of decay. “Do not be fooled,” Crace admonishes his reader early on:

There was no beauty for them in the dunes, no painterly tranquility in death framed by the sky, the ocean and the land, that pious trinity in which their two bodies, supine, prone, were posed as lifeless waxworks of themselves, sweetly unperturbed and ruffled only by the wind. This was an ugly scene. They had been shamed. They were undignified.

Yet Crace lingers almost lovingly over Joseph and Celice’s bodily transformations as they lie exposed among the seagrass. While their love life is painfully prosaic, the passages that describe their undiscovered bodies flirt with a far more idealistic vision of human attachment:

But the rain, the wind, the shooting stars, the maggots and the shame had not succeeded yet in blowing them away or bringing to an end their days of grace. There’d been no thunderclap so far. His hand was touching her. The flesh on flesh. The fingertip across the tendon strings. He still held on. She still was held.

Being Dead manages to recast our bodily afterlives as something not only speakable, but significant. It does so, however, by valorizing the unconscious peace of our material remains, casting that as preferable to the despicable fumblings of actual life. The intimacy of Joseph and Celice is only unproblematic when they have become unfeeling matter, generously supplying the landscape with the nutrients sloughing off their unprotected flesh. If Being Dead achieves an unusually death-positive outlook, it achieves it by becoming decidedly life-negative.

George Saunders’s more recent exploration of experience after death takes a radically different approach. Whereas Being Dead aligns itself with a kind of scientific detachment, Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo proves exuberantly grotesque from the outset. The story opens with the middle-aged Hans Vollman describing his gradual, tender seduction of his young wife. Alas, on the very day she promises to give herself to him, a loose beam falls and crushes his skull. Unable to accept the fact of his permanently unconsummated marriage, Vollman haunts the cemetery where he is buried, joining a number of other lingering spirits who convince themselves they are merely sick and will soon recover.

George Saunders’s more recent exploration of experience after death takes a radically different approach. Whereas Being Dead aligns itself with a kind of scientific detachment, Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo proves exuberantly grotesque from the outset. The story opens with the middle-aged Hans Vollman describing his gradual, tender seduction of his young wife. Alas, on the very day she promises to give herself to him, a loose beam falls and crushes his skull. Unable to accept the fact of his permanently unconsummated marriage, Vollman haunts the cemetery where he is buried, joining a number of other lingering spirits who convince themselves they are merely sick and will soon recover.

Saunders does not deal with decomposition in the straightforward way favored by Crace. His dead characters experience a progressive material instability instead, as they undergo bodily embarrassments that range from the familiar to the fantastic. Hans’s earthly fixations, for example, make him appear to other spirits with an oversized and irrepressible erection. He repeatedly bumbles into discussion of his physical shortcomings, from the baldness and lameness that plagued him in life to the mortifying fact that he pooped his pants after death. His fellow revenants suffer similar corporeal distortions: Roger Bevins III, a Whitmanian poet who killed himself in a fit of passion, fights to suppress the shapeshifting, hungry bundles of hands and eyes that sprout from his body in futile attempts to grasp after the experiences he denied himself by taking his own life.

If death positivity means staring unpleasant facts in the face, Being Dead would seem to be a more death-positive novel than Lincoln in the Bardo. Crace treats both the issue of decomposition and the unconsciousness of the dead in frank terms, whereas Saunders passes over putrefaction to depict a world where the dead might yet live — at least temporarily. But reading the texts together suggests that death positivity cannot emerge from objective attention to facts alone. In fact, Lincoln in the Bardo reveals that the fascination with prurient facts that underpins Being Dead emerges from a kind of puritanical fear of our fleshly existence, a fear inseparable from the novel’s reliance on an omniscient narrator.

We have become comfortable with the idea that a story can be told by the all-seeing eye of a disembodied voice. Strictly speaking, however, this supposedly objective “view from nowhere” is an absurd fiction — at least as impractical and unrealistic as any postmortem point of view. The impracticality of objective narration is especially apparent in Being Dead because the novel is so preoccupied with death, the very moment supposed to divide subjective from objective existence.

10 Death-Obsessed Books to Satisfy Your Inner Goth

By viewing the bodily histories of Joseph and Celice from the outside, the narrator of Being Dead does them — and us — a disservice. The novel only pretends to a fearlessly honest account of human bodies, when its perspective is essentially fearful. Rather than acknowledging the embodied experience the author shares with his subject matter, it retreats into the sham detachment of an etherealized narrator, an imaginary voice pretending to possess unearthly objectivity.

The result is an impossibly disembodied account of what bodies are, one that ends up portraying all embodied consciousness as disappointing, limited, and pitiful. Rather than treating death as an inevitable part of a continuous material experience we all share, Being Dead idealizes it in the way it idealizes all objectivity: in Being Dead, death offers a welcome break from the painful awkwardness of embodied consciousness. Saunders, by contrast, dives with rollicking good humor into the oddness of bodies, acknowledging such awkwardness — and embracing bodies all the more for it.

Lincoln in the Bardo has no imaginary narrator watching earthly existence from the outside. The story is told through a series of (mostly dead) characters whose interwoven monologues clumsily strive to explain their current state while avoiding any admission of their own deaths. The result is a world — the Bardo — that seems, at first, sui generis, a marvelous oddity sprung from the mind of one of our foremost storytellers. Soon, however, it acquires an uncanny familiarity.

For all its unworldliness, the community Saunders depicts is very like our own. His novel is a gently satirical portrait of a society founded on an elaborate charade of death denial; the plot turns on the shades’ need to realize the absurdity of the fiction that they can avoid their own deaths. It begins with the introduction of a newcomer — a freshly dead soul who is promptly welcomed with Vollman’s raunchy monologue. But Vollman is suddenly (and hilariously) taken aback to discover that he has just told his tale of penises and poop to a young, innocent, sad-faced boy who turns out to be the president’s son, Willie Lincoln, who has died of typhoid fever in the early days of the Civil War.

The timing of this weirdest of historical fictions cannot be coincidental. As Doughty and others have observed, the American Civil War marks the starting point of the modern death industry. Embalming, once considered a ghastly and unnatural process, became mainstream in the United States when families faced with the logistical problem of transporting bodies intact over long distances — the bodies of soldiers who were dying in unprecedented numbers far from their birthplaces. Embalming solved the problem, but it required a new kind of expertise. Suddenly the preparation of bodies — once an intimate affair, largely the work of women who cleaned and dressed their dead at home — became an invasive professional process. The Civil War thus launched the profession of the funeral director into the mainstream, driving a wedge between Americans and their dead.

Saunders’s novel offers us a glimpse of a more intimate antebellum relation with the dead to remind us of what we lost. It offers a profoundly moving account of an entire community of people awakening to an awareness of their own mortality. The story is simple enough: the denizens of the cemetery welcome young Willie, then watch in confusion as Abraham Lincoln repeatedly returns to his son’s tomb after dark to open it and embrace the body. As they look on, the roving spirits begin to recognize the loathing of their own bodies that lies at the heart of their death denial. The spirits speak in a series of rapid epiphanies about their own self-hatred, triggered by the loving touch Lincoln bestows on his son:

To be touched so lovingly, so fondly, as if one were still —

—roger bevins iii

Healthy.

—hans vollman

As if one were still worthy of affection and respect?

It was cheering. It gave us hope.

—the reverend everly thomas

We were perhaps not so unlovable as we had come to believe.

—roger bevins iii

The intimate attachment of the dead with the living fills them — and us — with something other than horror. It provokes surprise that gives way to admiration and awe as the dead realize that their shared fate does not deserve the hatred they have wasted on it.

It is an impressive portrait of a world to come. Of course Lincoln in the Bardo is, finally, a fiction — and a deeply unrealistic one at that. Nevertheless, the novel’s fantastical qualities do not make it less useful to the death-positive movement. If anything, its very lack of realism clarifies the important role fiction must play in our collective struggle to reimagine our relationship with death.

Lincoln in the Bardo shows accepting death to be inextricable from accepting the oddness of bodies. In Lincoln’s repeated visits to the cemetery, the spirits discover an individual not only unafraid of bodies but positively in love with one. Lincoln’s conflictedness shows him loving his son as a physical being — even in his diminished, postmortem form — and indulging that love precisely because he knows the body cannot last, that he must finally let it go.

What Vollman, Bevins, and the others come to understand through Lincoln’s example is how to reattach their senses of identity to their bodies. They learn to be generous to themselves as messy material beings, to include both their bodily joys and their bodily fallibility into their essential understanding of what it means to be. When they accept this epiphany they vanish, receding into something beyond our reach. But that disappearance no longer feels like an abrupt rupture of subjective experience, or something at odds with life. Death becomes, instead, a kind of higher accomplishment — a letting-go that most of us are not yet ready to aspire to.

That kind of awed acceptance is finally unavailable to Being Dead. Crace’s novel revels in a species of passionless scientific accuracy whose view is finally less able to understand death, and less able to represent it, precisely because death is such a deeply subjective experience. Death, in other words, only happens to subjects, to embodied beings immersed in material experience. That is precisely the experience that Being Dead, like works of strict nonfiction, refuses to include.

Lincoln in the Bardo reminds us that it makes no sense to aspire to unflinching objective accuracy when we are all flinching, subjective, and messy bodily beings. The attempt to adopt a dispassionate perspective on death is itself an example of our absurd aspiration to inhabit an undying, unearthly worldview. It is at once unhealthy and impossible. Clinical detachment from our shared embodiedness is the most pernicious of fictions.

The attempt to adopt a dispassionate perspective on death is itself an example of our absurd aspiration to inhabit an undying, unearthly worldview. It is at once unhealthy and impossible.

The death-positive movement has already made enormous strides toward making death a subject of public discussion. What we need now, however, is an examination of death as more than just a matter of fact. We need new fictions that understand death as an imaginative challenge — a challenge that cannot be overcome by stricter adherence to objective detachment, the interminable piling of fact on fact. We need innovative modes of storytelling that can disabuse us of this unhelpful obsession with objectivity, stories that help us see physical matter not as an assuredly lifeless, senseless object we all eventually become, but as the very thing that defines and enables our existence — the thing from which life and mind continuously, mysteriously emerges. Only then will we be able to forge a way forward that leaves us unafraid of our shared inhabitation of our fragile, corruptible, beautiful bodies.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!