By Joe Smydo

“No.”

That’s what Kelli Jo Lovich said when she was asked to donate the organs of her 4-year-old son, Colbee, who died after suffering severe brain injuries last year in an ATV accident in Butler County.

But Mrs. Lovich recalled that Shannon Pribik, a procurement coordinator with the O’Hara-based Center for Organ Recovery and Education, persisted. Ms. Pribik answered questions, promised there would be minimal trauma to Colbee during organ recovery and agreed to stay by his side until the funeral director arrived for his body.

Mrs. Lovich relented. “He was only 4,” she said of Colbee, “but he loved to help.”

■ ■ ■

Procurement coordinators are on the front lines of the nation’s overwhelmed transplant system.

They approach families like the Loviches in the midst of a tragic loss and ask them — when their grief is raw and their spouse, child or sibling is tethered to machines in the intensive care unit — to donate their loved one’s organs so that others can live.

“When you do it for the first time, you feel like you’re invading their space,” said Linda Miller, who operates a University of Toledo graduate training program for coordinators. The program was founded in 2003 with CORE’s support.

The stakes are high.

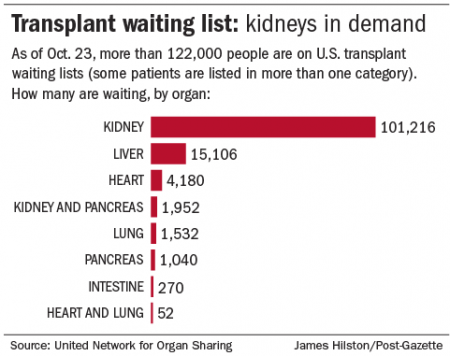

With more than 122,000 people waiting for transplants, and an average of 22 of them dying each day, coordinators face great pressure to recover organs from the roughly 2 percent of Americans who end their lives in a way — usually of brain injuries while on a hospital ventilator — that makes donation possible. People who die outside of a hospital cannot be donors because their organs deteriorate too quickly.

Sometimes, a family will say, “It’s just not for us. Let the next person be the donor,” said Jonathan Coleman, a coordinator at CORE.

Because donation can occur only in limited situations, he said, coordinators stress a family’s “unique opportunity” to turn its tragedy into somebody else’s second chance at life. Often, advocates say, the decision to donate a loved one’s organs — to let that person live on through others — sustains a family for years.

While demand for organs is growing, donation rates have been stagnant, with deceased donors numbering about 8,000 annually for the past decade.

Overall, procurement organizations — CORE is one of 58 nationwide — recover organs from eligible donors 73.6 percent of the time. CORE’s recovery rate is 82.7 percent, according to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

If a person had registered as a donor — the option is given at a driver’s license center, among other places — procurement organizations in Pennsylvania and most states have the authority to recover organs even if relatives object. If the person was not registered, coordinators try to persuade the family to donate the organs.

Some people balk at the prospect of organ donation because of fear that doctors will let the prospective donor die to save others waiting in the wings for transplants. While advocates insist that does not happen, procurement organizations have been sued at least twice by those who claim it did.

In 2009, Michael and Teresa Jacobs sued CORE, Hamot Medical Center in Erie, Pa., and several doctors, alleging that their 18-year-old-son, Gregory, who sustained brain injuries in a snowboarding accident, was “intentionally killed … so that his organs could be harvested.” The defendants settled for $1.2 million but contended that they provided proper care.

In 2012, Patrick McMahon, a former coordinator, sued the New York Organ Donor Network, now called LiveOnNY, alleging that the organization pressured him and a doctor to have patients declared brain dead — despite signs of brain activity — so that families could be persuaded to donate organs. In court papers, the donor network denied the allegations. The case is unresolved.

In 2012, Patrick McMahon, a former coordinator, sued the New York Organ Donor Network, now called LiveOnNY, alleging that the organization pressured him and a doctor to have patients declared brain dead — despite signs of brain activity — so that families could be persuaded to donate organs. In court papers, the donor network denied the allegations. The case is unresolved.

■ ■ ■

A former anesthesia tech, Mrs. Lovich once walked in on organ recovery surgery by mistake and blanched at the sight. Her reservations about organ donation were clear; Ms. Pribik recalled Mrs. Lovich’s silence and negative body language.

But Mrs. Lovich said Ms. Pribik’s promise that the cuts to Colbee’s body would be minimal — no greater than that required for regular surgery — softened her resistance to organ donation. Ms. Pribik’s promise to stay with Colbee until the funeral director arrived for his body — Mrs. Lovich didn’t want him “to just sit in a basement somewhere”— also helped. The thought of Colbee helping others moved her aching heart.

Coordinators are trained to address concerns and answer questions while guiding the family toward donation. Families often make special requests, and Ms. Pribik, who has held donor children in her arms, played their favorite songs in the operating room and kept treasured belongings near them, obliges when she can.

The job — with a starting base salary often in the low $60,000 range, Ms. Miller said — can be physically and emotionally grueling. Shifts of 24 hours or longer are common. Many coordinators, including Ms. Pribik, come from the nursing ranks and have experience with end-of-life care.

Ms. Miller said her training program was founded partly because high turnover signaled a need for better job preparation. Of the 84 who graduated from 2004 to 2014, about 78 percent are still in the field, she said, calling that a “very good” rate.

“I tell them every tough thing about this job,” she said.

Some coordinators are embedded in hospitals, but others travel as needed to hospitals in a procurement organization’s service area. CORE’s territory — encompassing five transplant centers, dozens of other hospitals and 46,177 square miles in Western Pennsylvania and parts of West Virginia and New York — is the 22nd largest in the nation.

Research and experience shape the strategies coordinators use. Ms. Miller said she speaks with her students about the “top 20 objections/concerns families might have” and urges them to ask “probing questions” to get to the root of unspoken fears.

“Then I have a bazillion scenarios, and we role-play, and we role-play, and we role-play,” she said.

A study of Texas cases published last year in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery suggested that female coordinators were more effective than males; that a family was more likely to consent to donation if approached by a coordinator of the same race; and that consent rates started to decline after midnight as families became fatigued.

Faced with the loss of a loved one, some families are dazed. Others are angry. “We are prepared for that,” Ms. Miller said.

■ ■ ■

The coordinator may start by reviewing patient data and huddling with the medical team to gain insight into family dynamics. Who are the decision makers? Is there conflict within the family? How are family members coping with the death?

“So far, I’ve never approached two families the same way,” CORE coordinator Wes Washington said.

One coordinator, interviewed for a 2011 article in the Journal of Health Communication, said gathering information about family members from a distance helps to provide important insights “long before they even know who I am.”

The article quoted another coordinator as saying he considers a lab coat a barrier to communication and takes his off before meeting with a family. If he senses that a necktie would create a “class barrier” with a family, he said, he removes that, too.

Families sometimes hesitate about donation because they don’t want further trauma to a loved one’s body. In those cases, coordinators explain that cuts will be as limited as possible and dignified and will not prevent an open-casket viewing. If the loved one died a tragic or unexpected death, the coordinator may point out that an autopsy is likely anyway.

Coordinators often suggest that donation would be a heroic act in keeping with the patient’s good character.

“We don’t ask the family. We offer them the opportunity. I really feel I’m giving them something good,” CORE coordinator Amy Weisgerber said.

Jenna LaSota, a Beaver County native who graduated from the Toledo program in July and works for Kentucky Organ Donor Affiliates, said she has found that families are receptive to the message and “want that good to happen.”

Ms. Pribik said donation also gives a measure of control to families who feel powerless after a tragic, unexpected death.

Some coordinators had used a “presumptive” approach and met a family with the expectation that it will donate after understanding the benefits. Ms. Miller said some in the field consider that approach “too strong” or “somewhat manipulative.” She said she teaches a “sensitive, effective family approach” that allows coordinators to better tailor their strategies to each family.

Some scholars and doctors have criticized coordinators for being too pushy. “Even seemingly caring and compassionate statements — like, ‘Would you like me to give you some time before you make your decision?’ — are discouraged in favor of language that rushes families along the preferred decisional pathway,” Robert Truog, a Harvard Medical School ethicist, wrote in 2012 in the American Journal of Bioethics.

Michael Grodin, a physician and ethicist at Boston University School of Public Health, agreed that coordinators sometimes are overzealous in their quest to keep organs from slipping through their grasp. Better for some organs to go unused than to undermine the public confidence that anchors the transplant system, Dr. Grodin added, calling for more transparent and verifiable standards for diagnosing death-by-brain criteria.

Coordinators say they are committed to ethical treatment of families. “I say, ‘That’s me in there. … What kind of person do I want talking to me and how do I want them talking to me?” CORE’s Mr. Coleman said.

Ms. LaSota said the coordinators she observed during her internships treated families with respect. “They didn’t try to push them or make it a big deal … .”

Some public education campaigns encourage family members to discuss donation so that, in the event of a tragedy, a loved one’s preferences are known and survivors have one fewer decision to make. A sudden death “is not the time to be thinking about organ donation for the first time,” said transplant advocate Kim Harbur of Kansas.

■ ■ ■

After consenting to donation and completing paperwork, family members are encouraged to go home.

But for the coordinator or coordinators — some work in teams — hours of work still are ahead. Organ systems must be evaluated, the data entered into a national database, prospective recipients identified and offers made to transplant centers.

The coordinator also must maintain the condition of a body that, without brain function, becomes unstable. Electrolytes go out of balance and body temperature and blood pressure drop — all changes that can damage the organs.

As soon as possible, procurement organizations give donor families welcome news. Mrs. Lovich learned that Colbee’s kidneys had gone to a man and a woman, both in their late 50s, and his heart valve to an 11-month-old baby.

She has continued to stay in touch with Ms. Pribik and has registered as a donor so that she has a chance to follow Colbee’s example.

“If my son can do it,” she said, “I can do it.”

Complete Article HERE!