By

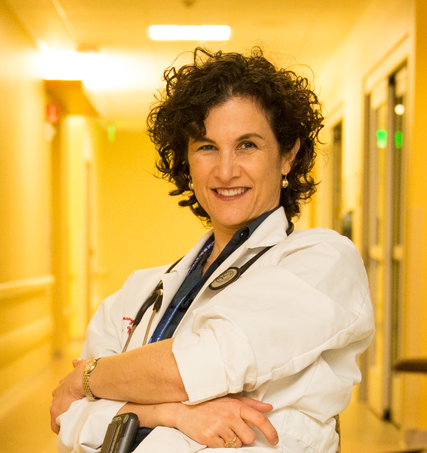

[W]hile confronting the prospect of death, people like me — grappling with a diagnosis of advanced cancer — often consider what sort of care they want and how to say goodbye. Given the delicate negotiations in which the dying need to engage, do intensive care physicians with their draconian interventions act like proverbial bulls in a china shop? My fear of pointless end-of-life treatments, performed while I was in no condition to reject them, escalated when I read Dr. Jessica Nutik Zitter’s book, “Extreme Measures: Finding a Better Path to the End of Life.”

Dr. Zitter confronts the sort of scenario that haunts me because she works in specialties that are sometimes seen as contradictory: pulmonary/critical care and palliative care.

In her new book, she refers to the usual intensive care unit approach as the “end-of-life conveyor belt.” She argues that palliative care methods should be used to slow down and derail the typical destructive I.C.U. approach that often torments people it cannot heal.

Over the past few years, quite a few studies have indicated that physicians are less likely than the general population to receive intensive care before death. Many doctors choose a do-not-resuscitate status. Dr. Zitter highlights the insight upon which her colleagues base their end-of-life decisions.

According to Dr. Zitter, even what are intended to be temporary intensive care measures can put a patient on that conveyor belt to anguish and isolation. She writes of breathing machines, feeding tubes, cardiac resuscitation, catheters, dialysis and a miserable existence prolonged within long-term acute care facilities. In an account of the evolution of her own ideas about doctoring, she also explains why it remains so difficult to change intensive care units so they can better serve the terminally ill.

“Extreme Measures” analyzes a complex cluster of suspect but ingrained attitudes that bolster hyperaggressive methods. Medical training fosters a heroic model of saving lives at any cost. American can-do optimism assumes all problems can and should be solved. Both doctors and patients tend to subscribe to a “more is better” philosophy. If technology exists, surely it should be used. Physicians’ fears of litigation plays a part, as do patients’ fantasies of perpetual life. For too many, death remains unthinkable and unspeakable.

One of Dr. Zitter’s compelling patient narratives teaches a clear-cut lesson. It involves an 800-pound man “too large to fit into the CT scanner,” but “too unstable to be transported to the nearby zoo’s CT scanner.” Surgery would therefore be impossible. The patient, a 39-year-old she calls Charles, is bleeding from his intestinal tract, his heart is exhibiting erratic behavior, his kidneys have failed and his liver is foundering. Yet he and his relatives want the doctors “to do everything.”

Although Dr. Zitter tries to explain to Charles and his family that chest compressions would break his ribs and electric shocks would burn his skin, they insist on “a full-court-press resuscitation attempt when he died.” To Dr. Zitter, “Running a code on this dying man felt… akin to punching him in the face and would probably have had the same utility.” Honoring his wishes would require breaking the oath: “First, do no harm.”

Other case histories in “Extreme Measures” are more troubling because their moral implications are less obvious. After a dramatic brain bleed from a major clot, a 45-year-old she calls George faces an operation that cannot return him to who he had been. His wife wants to know what Dr. Zitter would do if he were her husband. She explains that her husband would accept paralysis if he could remain communicative with her and their children at home.

Although Dr. Zitter fears that the surgeons who operated on George never broached the topic of his quality of life after surgery, she is heartened upon his return to the I.C.U.: He gives a thumbs-up. “What if, as a result of our talk, his wife had not consented to the surgery? Would I have been his unwitting killer?” This moment of self-doubt is followed by another turn of the screw. When Dr. Zitter later phones George’s wife, she says: “I am a single mother, but with another angry child.”

“Extreme Measures” includes a number of stories that explore the difficulties of talking about the subject of death with dysfunctional families, wracked by depression or feuds, and across racial, religious and ethnic divides. Often and to her credit, Dr. Zitter finds herself baffled, unsure of how to balance cultural priorities, human needs and medical possibilities. Throughout, she struggles personally and professionally to redefine common responses to terminal conditions.

In place of hope for recovery, Dr. Zitter emphasizes “the miracle of time at home, of pain management, of improved quality of life. These are all concepts I have seen families embrace in place of survival — the only concept of hope previously imagined.” And to people refusing “to play God” by withdrawing a breathing tube, she asks whether “they were playing God by keeping [a relative] alive when her body was actively dying.”

For readers who wish to avoid the end-of-life conveyor belt, Dr. Zitter concludes “Extreme Measures” with some practical advice on, for example, procuring a Physician Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST), a legal directive that emergency responders, paramedics and emergency room doctors are supposed to follow (but sometimes don’t, as Paula Span reported in The Times earlier this week).

Without this sort of documentation of end-of-life wishes, Dr. Zitter writes, a 90-year-old with metastasized prostate cancer ended up paralyzed and tethered to machines after cardiac arrests. “Our well-intentioned resuscitative efforts had crushed his cancer-weakened neck bones, rendering him quadriplegic.”

Passionately and poignantly, Dr. Zitter reminds us that “conveyor belts, regardless of their destination, are not meant for human beings.” Sometimes less is more.

Complete Article HERE!