— Grief in the age of AI

People are turning to chatbot impersonations of lost loved ones to help them grieve. Will AI help us live after we’re dead?

By Aimee Pearcy

When Sunshine Henle’s mother, Linda, died unexpectedly at the age of 72, Henle, a 42-year-old Floridian, was left with what she describes as a “gaping hole of silence” in her life.

Even though Linda had lived in New York, where she worked as a Sunday school teacher, the pair had kept in constant contact through phone calls and texting. “I always knew she was there, no matter what – if I was upset, or if I just needed to talk. She would always respond,” says Henle.

In November, Linda collapsed in her home and was unable to move. Henle’s brother Sam and her sister-in-law Julie took her to urgent care. The doctors found blood clots in her lungs and gave her anticoagulation medication. At first, “nobody seemed to be very concerned about anything,” says Henle. But over the next couple of days, there was a steep decline in her mother’s condition.

A couple of days later, Linda died.

At the peak of the early buzz surrounding ChatGPT in March, Henle, who works in the artificial intelligence industry, made a spur-of-the-moment decision to feed some of the last phone text messages and Facebook chat messages she had exchanged with her mother into the platform. She asked it to reply in Linda’s voice. It had been a few months since her mother had died, and while Henle had previously connected with a local therapist to help her cope with her grief, she found it disappointing. “It felt very cold and there was no empathy,” she says.

She told the chatbot she was upset because she felt like she had made mistakes and that the hospital had also made mistakes, and that she should have been there to advocate for her mother more. The program responded: “Remember the good times we shared. Remember my love for you and let that be your guide. Grieve, yes. Grief is the price that we pay for love. But don’t let it consume you. Remember to live, to love, to enjoy the beauty of this world for you, for me, for everyone who loves you. And sweetheart, remember to take care of yourself. You are so precious and I want nothing more for you to be happy. I’m very proud of you. I love with all my heart and soul.”

Henle was surprised by how much she felt seen by this technology. She also tried using Bard and Bing AI for the same purpose, but both fell short. ChatGPT was much more convincing. “I felt like it was taking the best parts of my mom and the best parts of psychology and fusing those things together,” she says.

While Henle had initially hoped ChatGPT would give her the chance to converse with what she describes as “a reincarnated version of her mother”, she says has since used it with a different intent. “I think I’m going to use it when I’m doubting myself or some part of our relationship,” she says. “But I will probably not try to converse with it as if I really believe it’s her talking back to me. What I’m getting more out of it is more just wisdom. It’s like a friend bringing me comfort.”

For all the advances in medicine and technology in recent centuries, the finality of death has never been in dispute. But over the past few months, there has been a surge in the number of people sharing their stories of using ChatGPT to help say goodbye to loved ones. They raise serious questions about the rights of the deceased, and what it means to die. Is Henle’s AI mother a version of the real person? Do we have the right to prevent AI from approximating our personalities after we’re gone? If the living feel comforted by the words of an AI bot impersonation – is that person in some way still alive?

Chris Cruz was shocked when his father, Sammy, died. He hadn’t thought it was serious when his father was admitted to hospital: he had been in and out of hospital several times before, having struggled with alcohol addiction for years since leaving their Los Angeles home when Cruz was only two years old. “Throughout my whole life there was this aura of danger about him,” says Cruz. “I thought: he’s been through much worse. This isn’t going to get him.” But after two weeks, Cruz received a call from his stepmother. Sammy’s condition had deteriorated. The hospice was asking her for permission to remove Sammy’s life support. Cruz immediately knew what his father would want: “I said yeah, go ahead and do it.”

It took a few weeks for him to fully process that his father was gone. “I was kind of numb from everything leading up to it. He had always had a turbulent relationship with his father, who would frequently make promises that would never materialize. “He tried to see me maybe once every couple of years. We would make plans and then at the last moment he would say that he has some work that he has to attend to,” says Cruz.

Cruz was inspired by an episode of Black Mirror to try to experiment with ChatGPT, but didn’t have high expectations. “I expected it just to not perform, or to give me some kind of response that was obviously created by a program,” he says. He fed ChatGPT old Facebook conversations with his dad and then typed out his feelings. “Just so you know, I’m really sad that you’re not here with me right now,” he wrote. “I’ve done so much since you’ve passed away and I have this great new job. I wish that you could see what I’m doing right now. I think you’d be proud.”

Cruz’s chatbot responded with a positive message of support and encouragement: “I know you’re going to do great things at your new job and your new position. Just remember to keep working hard and go to work every day.” This generic phrasing may not have sounded like his father, precisely, but still, Cruz felt a mix of relief and grief.

While Cruz said that ChatGPT helped provide him with a sense of closure, not everyone in his family understood. “I tried to tell my mom, but she just doesn’t understand what ChatGPT is and she refuses to learn, so it wouldn’t have done anything for her,” he says. When he told his friends, they gave him a half laugh. “They were like: ‘Is this an OK thing to do?’ Because I think it’s still an open question.”

Even before ChatGPT, the question of how to grieve, in a digital world, has become increasingly complex. “The dead used to reside in graveyards. Now they ‘live’ on our everyday devices – we keep them in our pockets – where they wait patiently to be conjured into life with the swipe of a finger,” says Debra Bassett, a digital afterlife consultant.

As far back as 2013, Facebook launched memorial profiles for the dead after receiving complaints from users who were receiving reminders of dead friends or relatives through the platform’s suggestions feature. But some platforms are still struggling to figure out how to memorialize the dead. In May, the CEO of Twitter, Elon Musk, was heavily criticized after tweeting that the platform would be “purging accounts that have had no activity at all for several years”. One user tweeted: “My sister died 10 years ago, and her Twitter hasn’t been touched since then. It’s now gone because of Elon Musk’s newest farce of a policy.”

But until recently, those digital memorials have mostly been places for catharsis. A friend or family member might post a comment on a page, expressing loss or grief, but no one responds. With artificial intelligence, the possibility has emerged for a two-way conversation. This burgeoning field, sometimes called “grief tech”, promises services that will make death feel less painful by helping us to stay digitally connected with our loved ones.

This technology is increasing in use across the world. In 2020, South Korea’s Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation released a VR documentary film titled Meeting You, which features a mother, Jang Ji-sung, meeting her deceased seven-year-old daughter, NaYeon, through VR technology. Jang is in floods of tears as she tells her daughter how much she missed her. Later, they share a birthday cake and sing a song together. It feels both moving and manipulative. Occasionally, it flickers back to reality: Jang is standing in a studio surrounded by green screens, wearing a VR headset.

In China, the digital funeral services company Shanghai Fushouyun is beaming life-like avatars of the deceased on large TV screens using technologies such as ChatGPT and Midjourney – a popular AI image generator – to mimic the person’s voice, appearance and memories. The company says this helps their loved ones to relive special memories with them and allows them to say a final goodbye.

In the US, the interactive memory app HereAfter AI promises to help people preserve their most important memories of loved ones by allowing them to record stories about their lives to share interactively after their deaths.

James Vlahos, the co-founder of HereAfter AI, created a precursor to the platform in 2016, soon after his father was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer.

“I had done a big oral history recording project with him, and I had gotten this idea that maybe there would be a way to keep his voice and stories and personality and memories around in a different and more interactive way,” says Vlahos. Together, Vlahos and his father recorded his father’s key memories, including his first job out of college, his experience of falling in love and the story of how he became a successful lawyer.

In 2017, Vlahos wrote about this experience in Wired. After it was published, he heard from other people who were facing loss, and who felt inspired by his creation. He decided to scale the app so that others could use it, leading to the creation of HereAfter AI.

The platform lets people turn photographs and recordings into a “life story avatar” that friends, family and future generations will be able to ask questions to. So a son could ask his mother’s avatar about her first job and hear memories that his real mother had recorded in her actual voice while she was still alive. AI is used to interpret the questions asked by users and find the corresponding content recorded by the avatar creator.

HereAfter ensures that the deceased have given permission for the voice to be used in this way before they die, but ethical questions still loom large over two-way interactive digital personas, particularly on platforms like ChatGPT which can impersonate anyone without their consent. Irina Raicu, the Internet Ethics Program director at Santa Clara University, says that it is “very troubling” that AI is being used in this way. “I think there are dignitary rights even after somebody passes away, so it applies to their voices and their images as well. I also feel like this kind of treats the loved ones as kind of a means to an end,” she says. “I think aside from the fact that a lot of people would just be uncomfortable with having their images and videos of themselves used in this way, there’s the potential for chatbots to completely misrepresent what people would’ve said for themselves.”

A number of technology ethicists have raised similar concerns but the psychotherapist and grief consultant Megan Devine questions whether there really is a line that technology should not cross when it comes to helping people to grieve. “Who gets to decide what ‘helping people grieve’ means?” she asks.

“I think we need to look at the outcome in the use of any tool,” she says. “Does that AI image soothe you, make you feel still connected to her, bring you comfort in some way? Then it’s a good use case. Does it make you feel too sad to leave the house, or make you lean too heavily on substances or addictive behaviors? Then it’s not a good use case.”

Raicu says that the benefits to the user shouldn’t come before the rights of the dead. Her concerns are based on real events. Last year, the Israeli AI company AI21 Labs created a model of the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a former associate justice of the supreme court. The Washington Post reported that her clerk, Paul Schiff Berman, said that the chatbot had misrepresented her views on a legal issue when he tried asking it a question and that it did a poor job of replicating her unique speaking and writing style.

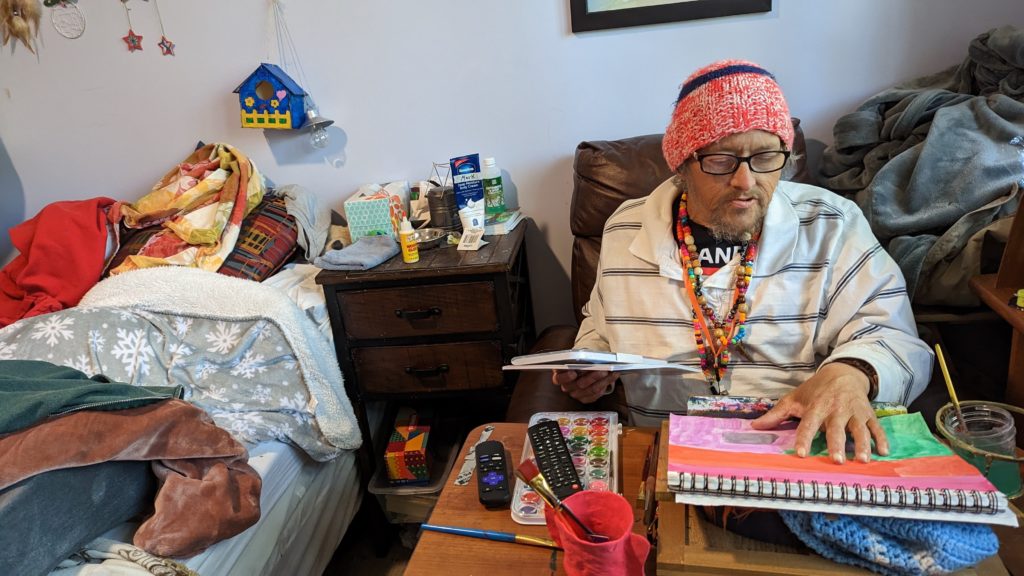

The experience can also be unpleasant for these seeking solace. Chris Zuger, 40, from Ottawa, Canada, was also curious to find out whether ChatGPT would be able to imitate his late father, Davor, based solely on the speech patterns of a set of provided prompts.

His father had been hospitalised months previously after a fall. Zuger raced to the hospital when he heard the news, but never got the chance to say goodbye.

“Being brought to the room, I knew very well what the news was going to be. My mother, not so much. Seeing her reaction was devastating,” says Zuger.

Davor, who Zuger describes as a “larger than life character”, was the youngest of 14 children. He was born in a small village in Croatia soon after the second world war. “He was the type of guy who wanted to make sure that his kids had the opportunities that he didn’t. He worked two jobs – just to be able to make sure that we had a roof over our heads and a fridge full of food.”

After going to therapy to help process his grief, Zuger decided to feed in some of his father’s text messages and provided ChatGPT with a description of his father’s speech patterns. Then, he sent a message: “Hey, how’s it going?” He did not keep a record of and can’t remember it word for word, but he remembers that it scared him.

“It was as close as I could figure as if my father were actually texting me,” he says. But it was also a painful reminder that his father was really gone. “It’s not a text from him on my phone. He’s not across the city at his phone typing to me. It’s just prompt, regurgitating back output from its own language model. It was difficult to see the messages while knowing they were not real.”

If his father had known his son had used ChatGPT to recreate his conversations, says Zuger: “He would have thought it was wild and then asked me how to use it. He would have had fun with it. It probably would have got him off Facebook.”

Bassett, who advises technology companies on their treatment of the deceased, refers to the dead whose digital likenesses are manipulated to perform in ways they may not have while alive as digital zombies. Famous examples include Tupac Shakur and Michael Jackson, who have both been digitally recreated to perform live on stage at concerts years after their deaths.

To prevent people from being recreated with technology against their wishes, Bassett presents the idea of a digital do-not-reanimate (DDNR) order – inspired by the physical do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order, which could be part of a person’s will. Vlahos also emphasizes that enthusiastic consent from the deceased should be a requirement for using this technology. He says that one of the biggest challenges that he faces is that many people don’t realize that they want to use this technology until it’s too late for content to be obtained and the required information provided. “It’s something that people kind of think can be put off for another day,” he says. “And then that day doesn’t come. We get a lot of inquiries from people saying that a relative has already died, and asking if we can do something for them. And the answer is no.”

In the future, however, some element of digital afterlife may prove impossible to avoid, whatever our wishes, in part because the development of many AI products has outpaced the ethical questions that surround them. “For most of us who live in the digital societies of the west, technology is ensuring we will all have a digital afterlife,” says Bassett. Even if our conversations are not being fed into a chatbot, our online activity is likely to remain online for others to see for years to come after we die – whether we like it or not.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!