The way doctors give patients bad news can teach us all something about how to have hard conversations

[I]t’s not uncommon for Andrew Epstein to spend sleepless nights replaying scenes from his day and wondering what more he could have done for his patients. Often, the answer is nothing—but that still doesn’t help his insomnia.

Epstein is an oncologist at the Sloan Kettering Memorial Cancer Center in New York. His job requires conversations with patients who are extremely sick. Sometimes, he’s breaking the news of the severity of their illness to them; other times, he’s telling them the treatment they thought may work has failed, and it’s time to begin preparing for end-of-life care.

Each encounter is so emotionally draining, he can only do it for about half of the week; he spends the rest of his time preparing for future conversations with new patients, or recovering.

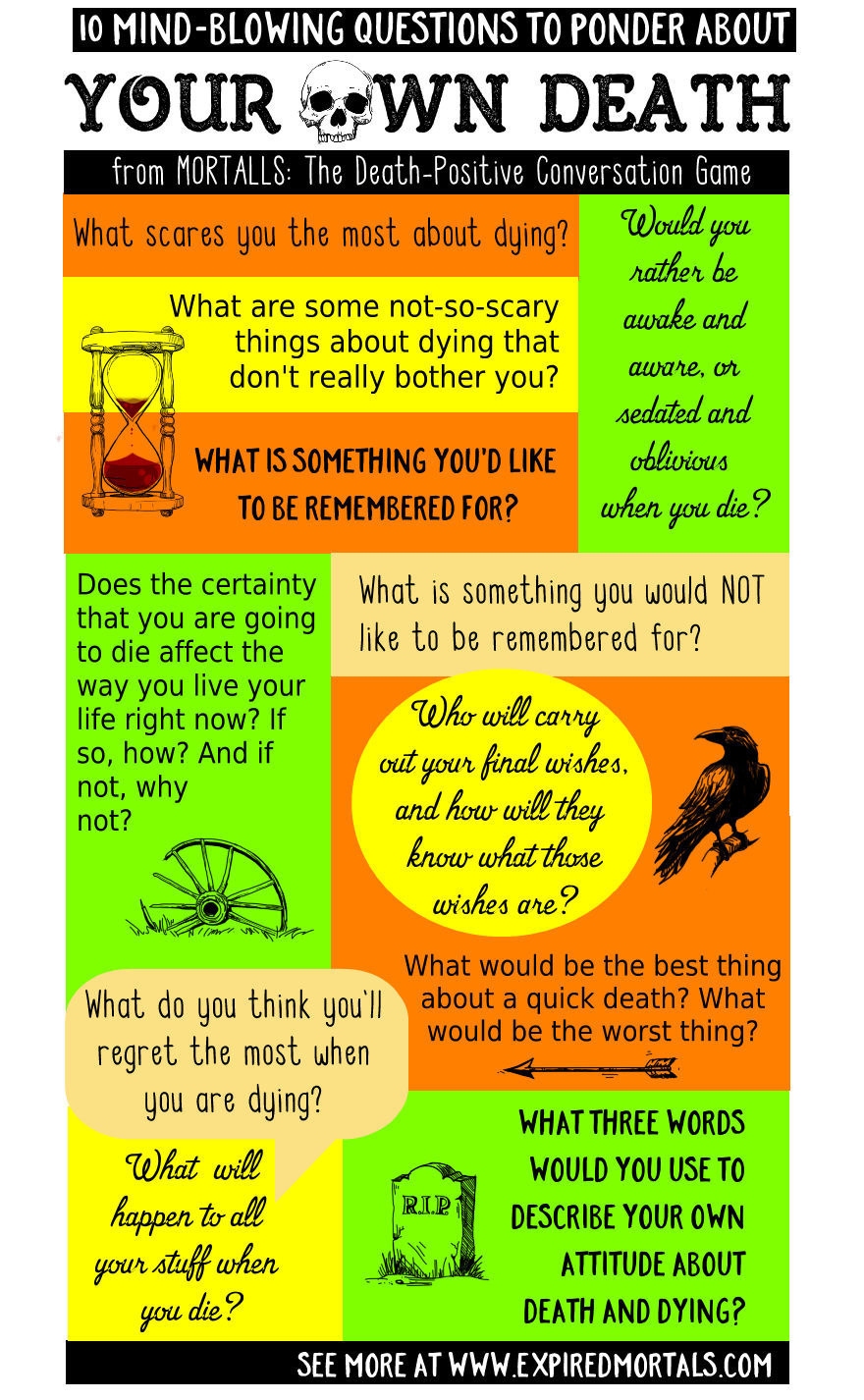

Telling patients and their families that they must face their own mortality is one of the most difficult things that has to get done in the medical profession. Most patients want to have conversations about care at the end of their lives, but often don’t end up having them—probably because many doctors are not prepared to do so, despite training as part of medical school.

Not all of us will have to have these kinds of grim conversations, but we will all have to disappoint people at some point. Maybe you won’t ever have to tell someone they are going to die, but you might have to deliver a bad performance review, let someone go, or break up with a partner. It will never be seamless, but there are ways to be a better bearer of bad news, and lessen the emotional pain for others.

“It’s all about self-awareness, preparation, respect for others and inquiry into [their] perspective,” Epstein says.

First, you have to actually call a meeting—don’t wait for a chance encounter to deliver of bad news, and don’t put it off. “You want to have a comfortable, private setting, arrange for the meeting, and don’t meet any later than necessary,” says Jayson Dibble, a communication specialist at Hope College in Holland, Michigan. Delaying bad news means the recipient has less time to react and move on.

Setting the appointment shows that you are giving your full attention, and allows whoever you need to talk to the time to prepare themselves emotionally for the news, even if they don’t know exactly what that news is. It shows that both you are willing to commit your time to them, and that you respect the time they are giving up for you.

Once you’ve set the meeting, you need to get fully prepared. Epstein pours over his patients’ charts and imagines himself in their shoes, trying to figure out the questions they are most likely to ask. He also makes sure that he’s ready to translate medical jargon into practical facts the patient can use to make a decision about their care.

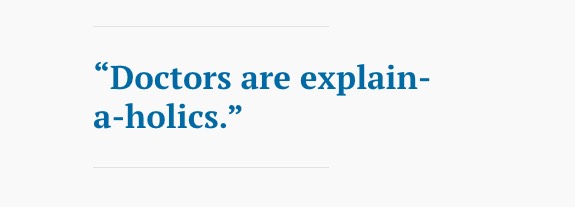

“Doctors are explain-a-holics,” he says. Understandably, medical professionals don’t want patients to lose hope, so they’ll start going through all the additional tests they could run and explaining all the experimental treatments available the patient could try. This, though, is a form of stalling, and doesn’t give the patients the information they actually need to hear.

“Doctors are explain-a-holics,” he says. Understandably, medical professionals don’t want patients to lose hope, so they’ll start going through all the additional tests they could run and explaining all the experimental treatments available the patient could try. This, though, is a form of stalling, and doesn’t give the patients the information they actually need to hear.

To avoid being overly optimistic, take time to think about why you need to have this particular conversation, Dibble says. In most cases, the goal is to give the person you’re talking to what they need to take control of their situation.Compassion is important, but being too hopeful may give the impression that the situation is not as serious as it actually is—which may lead whoever you’re talking to react improperly, and end up worse off later on.

Keeping these end goals in mind can help frame the discussion. Consider breaking up with a partner: It’s never to hurt his or her feelings. The end goal of dating is to find someone you want to pursue a deeper relationship with. Both people deserve to feel respected and loved, and if one person can’t give that to the other for whatever reason, both are missing opportunities to find someone else who can. Or think about the workplace: if your job is to give a negative performance review to an employee, it’s not to make her feel incompetent; it’s to figure out how to make her (and the company) better.

Epstein has found that one of the keys to successfully communicating the most grim is getting to know the patient’s values in advance. As surgeon and writer Atul Gawande notes in the New Yorker, “People have concerns besides simply prolonging their lives.” Patients often prioritize the quality of their remaining time, making decisions based on how long they’ll be able to care for themselves, converse with loved ones, or keep up certain hobbies.

Once you have a plan of the information and its framing, there’s the actual delivery. When actually speaking, “be polite, but clear,” Dibble says. “If you don’t know the answers, it’s okay to say ‘I don’t know.’”

As much as you may want to speak to fill the silence after saying your piece, you shouldn’t. “After the bad news, we [tend to] fill the silence with a lot of words, and instead what we should do is shut up,” says Epstein. When doctors continue to spew out medical jargon, he says, it’s a way of making an uncomfortable situation more comfortable for them, rather than those they’re caring for. “In the end, we do the patient and family a disservice.”

In fact, you should take advantage of pausing, Dibble says, because it gives you and the receiver an extra moment to digest and prepare for the next bit of info. Often, we can’t fully comprehend new information when our brains are occupied with too much emotion. It’s one of the reasons that eye-witness reports for crimes are often unreliable: when stressed, we can’t store new facts thrown at us.

In fact, you should take advantage of pausing, Dibble says, because it gives you and the receiver an extra moment to digest and prepare for the next bit of info. Often, we can’t fully comprehend new information when our brains are occupied with too much emotion. It’s one of the reasons that eye-witness reports for crimes are often unreliable: when stressed, we can’t store new facts thrown at us.

In order to help the recipient process information, you should acknowledge and validate some of those initial emotions. When patients are faced with devastating news, they won’t be able to digest practical information right away, Epstein explains. “They need quiet, and then some phrase to address their emotion, to empathize,” he says.

There’s no one way to go about this part, though. Not everyone reacts to bad news the same way. Some people cry, others get angry, and others remain stoic as shock sets in. Others will demand a reason why they’re hearing this painful news. Depending on the person you’re speaking with, you may have to adapt your strategy as you go along to address their needs while keeping the end goal of the conversation in sight.

There are some mnemonic devices that health care professionals use to navigate these situations. For example, NURSE stands for Naming an emotion, Understanding and Respecting the patient’s reaction, offering Support, and asking him to Explain what they’re feeling further. There’s also SPIKES, which stands for Setting up an interview, assessing the patient’s Perception, obtaining the patient’s Invitation, giving Knowledge and information, addressing the patient’s Emotion, and Summarizing the conversation” But, these should be guidelines—not a strict framework. “If used badly, it would sound robotic,” Epstein says.

In order to be fully present, empathy is key—continually imagining yourself on the other side of the conversation will help you be as generous and respectful as possible. But it’s also important, Epstein says, those delivering bad news need to know their own emotional limits. “If you get too emotionally mired in it, the care of other patients will suffer and you’ll burn out,” he says.

Complete Article HERE!