Changing the way we think and talk about death could improve end-of-life health care. Recent research suggests encouraging people to view death differently, as a positive and natural part of life, it could help them make better decisions as they prepare for what is inevitably to come.

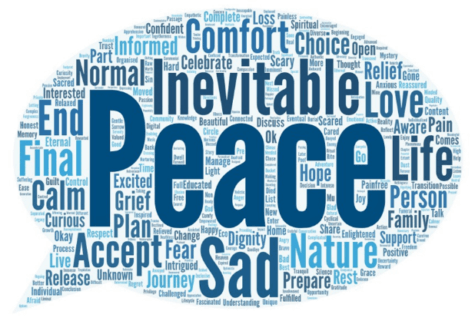

For many people, especially if someone has recently experienced loss, giving up the ghost is one of the most taboo topics. This is indicated in the words people choose to use when describing their feelings and insights into death or dying, researchers say. People who are not comfortable with the topic are more likely to choose emotional words such as “fear or scary,” whereas those who are more ready to meet their maker will use terms like “inevitable or natural.”

“In an aging population, when our elders and terminally ill are often cared for by health professionals in residential care rather than in the home, we can go through life without really discussing or witnessing the end of life. Tackling and changing these perspectives will help the community to plan for and manage future needs and expectations of care at end-of-life, and improve patient and family care, including greater preparedness for death. This can also help develop future health services,” says Dr. Lauren Miller-Lewis, study lead author of Flinders University in Australia, in a statement.

In a recent study, researchers surveyed 1,491 people to determine what language they used to describe their feelings when it came to dying. Participants were then enrolled in a six-week open online course dubbed Dying2Learn. The course, which ran from 2016 to 2018 and in 2020, encouraged people to have open conversations about death and dying.

The language participants used when discussing death before and after the course was analyzed using automated sentiment analysis. By the end of the course, participants were able to use more pleasant, calmer and in-control words to express themselves on the topic, researchers say.

“Words aren’t neutral, so understanding the emotional connotations tied to words we use could help guide palliative care conversations,” says Dr. Miller-Lewis. Younger participants showed the greatest increase in positive vocabulary, including pleasantness and dominance over the topic.

“It shows how the general public can gain an acceptance of death as a natural part of life by learning how to openly discuss and address these feelings and attitudes,” adds co-author Dr. Trent Lewis.

Differences in how participants talked about death with others rather than just explaining their own feelings were also observed by the researchers. When talking about someone else’s loss, participants were more likely to use words such as “sad,” “fear,” scary and loss. However, when it was about themselves they employed less emotionally negative words like “inevitable,” “peace,” and “natural.”

“The assumption was that others feel more negatively about death than they do themselves. This could impact on our willingness to start conversations about death with others,” says Dr. Lewis. “Do we avoid it because we think others will get upset if we bring it up, and does this then leave important things unsaid?“

The findings are published in the journal PLOS One.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!