By ANN NEUMANN

MY FATHER’S WAKE

How the Irish Teach Us How to Live, Love and Die

By Kevin Toolis

275 pp. Da Capo. $26.

[I]n his 2015 book “The Work of the Dead,” Thomas W. Laqueur takes up an ancient question: Why do we care for the bodies of the dead when we know that after our loved ones have left them they are empty shells? He begins his query with Diogenes, the eccentric fourth century B.C. philosopher who requested that his dead body be thrown over the city walls to be devoured by beasts. The corpse may be waste, “meat gone mad,” James Joyce wrote in “Ulysses,” but since our beginnings we have endowed corpses with cultural and symbolic significance. “Whatever our religious beliefs, or lack of belief, we share the very deep human desire to live with our ancestors and with their bodies. We mobilize their power,” Laqueur wrote.

The journalist Kevin Toolis does not doubt that corpses have particular superpowers. In his new book, “My Father’s Wake,” the bodies of our dead are life lessons, moral instructors of how to have satisfying lives and peaceful deaths. The tradition of the Irish wake, with rituals that predate Christianity, is our legend, “the best guide to life you could ever have,” he writes.

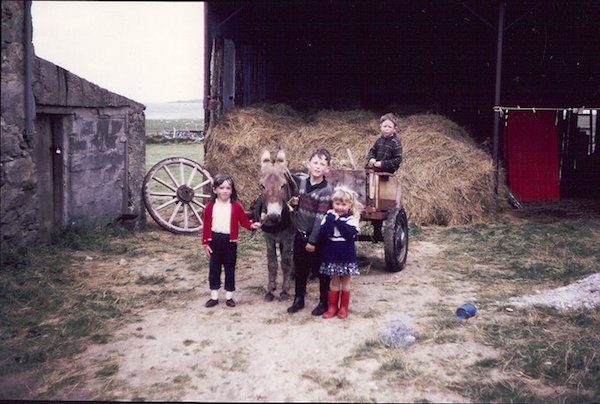

“My Father’s Wake” is at heart a memoir, chronicling a childhood spent between Edinburgh and remote Achill Island off the western coast of Ireland’s County Mayo, where his parents were born. When Toolis is 19, his brother Bernard dies of leukemia. He is his brother’s keeper, a bone marrow donor, but the transplant fails. The trauma sends Toolis as a young reporter out into the world, from Somalia to Afghanistan, in search of death, disease, famine and war. “I was grieving,” Toolis writes. “Not for my dead brother but for the young man who died with him and lost his mortal innocence. Me.”

The contrast between young Bernard’s death (in the city, in the care of what Toolis calls the “Western Death Machine”) and his father Sonny’s death (at home in old age on Achill) sets up Toolis’s castigation of modern medicine and death rites. But it is Toolis’s fine skill at showing the means and aftermath of death rather than his prescription for how to improve dying that most animates “My Father’s Wake.”

“Under the greenish light of a fluorescent tube, Eliza’s hands writhed involuntarily at her wrist as if seeking to escape their dying host,” he writes of a 20-year-old Malawian girl who dies in the middle of the night of AIDS. In the local dialect, Toolis tells us, the disease is known as matantanda athu omwewa, “this thing we all have in common.” Toolis’s writing is so visceral and profound when he is near dying bodies that the lessons of such experiences become evident — so evident, indeed, that the unfortunate framing of “My Father’s Wake” as a how-to for urban Westerners feels a bit clumsy and redundant.

“Under the greenish light of a fluorescent tube, Eliza’s hands writhed involuntarily at her wrist as if seeking to escape their dying host,” he writes of a 20-year-old Malawian girl who dies in the middle of the night of AIDS. In the local dialect, Toolis tells us, the disease is known as matantanda athu omwewa, “this thing we all have in common.” Toolis’s writing is so visceral and profound when he is near dying bodies that the lessons of such experiences become evident — so evident, indeed, that the unfortunate framing of “My Father’s Wake” as a how-to for urban Westerners feels a bit clumsy and redundant.

Early in the book, Toolis implores us to face our mortality by calculating the date of our death, “the end point for you.” In the book’s final chapter, “How to Love, Live and Die,” he offers this advice: “If you can find yourself a decent Irish wake to go to, just turn up and copy what everyone else is doing,” and “take your kids along too if you can.”

These bookends undermine Toolis’s manifest intellectual curiosity about contemporary medical and funerary practices. Studies indeed show that when dying patients plan for and accept their impending death, their family members more ably manage grief, but Toolis never sheds light on why that is. Nor does he identify where or how the funeral industry — “the dismal trade,” as Jessica Mitford called it in 1963 — has gone wrong. Grievers in funeral homes touch their corpses too.

I can’t help wishing that Toolis had kept the beautiful memoir of his life-and-death experiences and thrown the self-help curriculum over the city walls to be devoured by beasts. There really is no greater truth than a corpse.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!