By Katy Reckdahl and Christiana Botic

Three years ago, Robert Turner, a retired computer analyst in New Orleans, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. So far, Turner, 63, only feels slightly stiff and a bit slower in his motion. “I tell my doctor I’m on the 20-year plan of surviving this,” he said.

Still, because Parkinson’s is progressive, his sister, a geriatric nurse, imagines the worst.

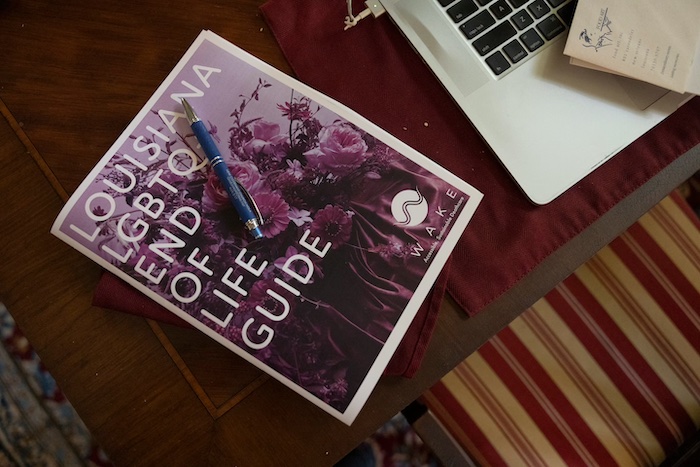

So Turner spent part of last week leafing through the 35-page Louisiana LGBTQ+ End of Life Guide, created in New Orleans about a year ago. It’s thought to be the first of its kind in the United States.

He’s been focused mainly on the guide’s first of four sections, called “When You’re Well,” which deals with Louisiana law and death planning, advance directives and wills. “I’m not ruling out a future husband, but there’s not one currently,” he said, as he outlined where his possessions will go and who can make funeral arrangements for him.

Turner understands the stress of not having the proper legal framework in place when a loved one passes. “It’s just one of those things that we all put off and we all need to do,” Turner said. “My first husband died of AIDS in the early ’90s. We had scheduled a lawyer to come visit him in the hospital the next day, and he died that night.”

“Louis was really my first boyfriend, my first partner, my first husband, even though gay marriage was, of course, not legal in Louisiana then,” Turner said. “I didn’t have anything legal to show for his estate that he was my partner.”

The guide is the brainchild of Ezra Salter, 31, a funeral director in suburban New Orleans.

The onus to create this comprehensive guide came after Salter started dating their partner, Keira, a transgender woman. Salter, who identifies as nonbinary, was shocked at the disapproval that came from family. Salter feared what might happen if one of them died but couldn’t find a centralized, readily accessible resource to help them navigate the issue.

Neither of the pair have changed their names legally, and though relationships with family are improving, the tensions have remained. Salter’s parents haven’t met Keira during the 10 years they have been together. Some members of Keira’s family still refer to her by the name she was given at birth, known as a “deadname.”

In collaboration with several experts, Salter published the Louisiana LGBTQ+ End of Life Guide in 2022.

Salter said they frequently hear from guide users that “‘I never thought of this, I thought that power of attorney was enough,’ and not fully understanding the depth of what they need to protect themselves.”

“Getting documents in line prevents some heartaches,” Salter said of planning for death for unmarried couples in the LGBTQ+ community. “It’s difficult to see someone struggle with the idea that the husband who they used to sleep next to every night is sitting dead in a cooler because you can’t cremate them earlier unless you have this magic piece of paper.”

The family tension Salter speaks of is a common experience among members of the queer community. It makes the guide a necessity.

Nicholas Hite, of the Hite Law Group in New Orleans, founded his own law group in 2013 and focuses on LGBTQ+ representation. “Part of preparing, legally, for death is understanding that it’s most often not a lightning-bolt moment, where you’re alive one minute and dead the next, because of medical care and the nature of modern life.”

“For queer folks, your biological family — the people who are legally the next in line to make decisions — are oftentimes the last people that you want making your decisions,” he said. “So you need legal paperwork allowing your most closely held individuals — who aren’t necessarily married to you or related by blood — to be in the hospital and at the funeral home with you and on your behalf.”

Three years ago, because Ellen Stultz lacked such paperwork, she spent three months trying to claim the body of her close friend Oscar White, 62, who died without a partner or known family. “The situation was hard for me, still is really hard for me,” said Stultz, who has fond memories of French Quarter strolls and whiled-away afternoons at White’s apartment with his little family of adopted stray dogs.

After two months, she started to worry that White would be buried in an unmarked grave. She called the morgue every day, then connected with Salter through mutual friends. Within a week, she’d received a box in the mail containing White’s ashes.

“His death was so traumatic,” Stultz said. “Yes, this is something that happened, but it seems like it doesn’t have to.”

Stultz did all she could within the system to claim White’s remains. Though no one else was requesting them, the state would not release the remains because she was not a blood relative. “When I first called the morgue, they were like, ‘Wait and see if any next of kin comes to claim his body.’ And at this point, he’d already been there a month. They didn’t really have much advice except just, ‘Keep calling,’” Stultz said. “Once I got Ezra involved, having someone to advocate for me, that’s all it took.”

For gender-diverse people, death arrangements have added complications, said Salter, who often hears the same questions again and again. “Who’s going to handle my body when I die, and how can I make sure that they use the right name and the right pronoun?”

“As I became trained in funeral service, I asked specific questions a lot, to every professional I met,” Salter said. “I’d raise a lot of hypothetical questions —“I’m asking for a friend.” I made it my business to get these answers because it was not clear anywhere online. I kept what I call a ‘chaotic Google Doc’ of everything I knew about funeral services.”

“I put my own life and, sort of, my own transition on hold to gain knowledge and work in a system, so that I can then go help people outside of the system who still need to interact with this institution and, you know, bridge the gap,” Salter said of working in the corporate funeral industry.

Hospital policies rarely deal with what gender (or nongender) should be assigned on death certificates, said Dietz, a contributor to the Louisiana guide who works as an advocate for transgender health care. (Dietz uses a mononym, without a surname.)

Most often, gender determination is made by the doctor signing the death certificate. But gender markers from medical records can be unreliable, since transgender people who still need prostate exams or Pap smears — considered “gender-specific care,” may retain their birth gender, even if they change gender on driver’s licenses, Dietz said.

“Oftentimes, life feels so overwhelming to LGBTQ+ people, depending on your layers of intersecting identities that are oppressed. So it can be really hard to prepare for death when we’re trying so hard to live,” Dietz said.

Because laws and institutional policies vary greatly between states, the creators of the Louisiana guide hope to create similar guides for every state, through a partnership with the national death-care advocacy group the Order of the Good Death.

In Louisiana, all powers of attorney expire at the time of death, said Liz Dunnebacke, who helped publish the guide through her New Orleans nonprofit, Wake, which provides death-care information and resources.

So even if someone has prearranged their own funeral, their next of kin can legally override those plans. “Your estranged mother can blow in 30 years later, order a full Catholic service with rites and exclude your chosen family from the ceremony,” Dunnebacke said.

That nightmare can be averted through the Funeral and Disposition of Remains Directive, a newly minted, two-page form. “The legal code existed, but no document. So we created one, which we now make available,” Dunnebacke said.

The directive, once notarized, identifies who will make decisions about physical remains and funeral ceremonies. It is an essential step, both legally and emotionally, Hite said.

“You know, many of us spend our entire lives fighting to get control and autonomy over our bodies,” he said. “The guide empowers folks to continue to maintain control over themselves, even after they’re dead.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!