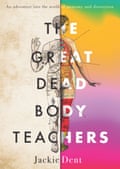

— Jackie Dent’s grandparents’ body donation was hardly discussed until a chance conversation set her on a quest to find out more about the secretive world of dissection

By Jackie Dent

Dissection might not be a normal topic to contemplate but when both your paternal grandparents donate their bodies to science it does intermittently cross your mind. My grandmother Ruby’s body went to the University of Queensland in 1969 and my grandfather Julie’s in 1981. Yes, that was his name.

The fact that both my grandparents’ bodies were dissected for science has always lurked within the family. For years, I’ve seen it as a slightly intriguing thing, quietly spectacular. A radical but slightly weird postscript to their ordinary lives. I mean, why would anyone do that?

Over the years, their donation had been very vaguely discussed in the family but not overanalysed. Or analysed at all really. Nobody seemed to wonder much about what had actually happened to Julie and Ruby.

But one hot Sydney summer, everything changed. I was at my parents’ place and their neighbour asked us over for a Christmas drink. As we chatted over sparkling wine, one of the daughters updated us on her new job. She was working at a university and hospital teaching facility and mentioned that some medical students are no longer using full bodies for dissection. She also said that human arms and body parts were being shipped in from the US.

I was stunned. Why aren’t they dissecting full bodies? And why do they have to fly in arms?

She wasn’t sure.

We finished our drinks, said “Happy Christmas” and I went home perplexed.

Over the ensuing weeks, the conversation at Christmas niggled. Had Australians really stopped donating? But also, come to think of it, what happened to Ruby and Julie all those years ago? Did I really want to know? As a Harvard professor told the 1896 meeting of the Association of American Anatomists: “We know only too well that dissection is an abomination to the popular mind.”

What was I hoping to find out? I maybe wanted to know the gory details of dissection, the slicing and chopping but was nervous as I’m quite squeamish. I wondered what the anatomy lab looked like, who was in the room. I wanted to know if what had happened to their bodies mattered, what it meant to the students. Were they respectful?

But their bodies went to the university so, so long ago, 50 years. How would I even find the people who were in the room back then? And would they talk? The whole business felt so secretive.

So I began tracking down old surgeons, doctors and technicians who were in the dissecting rooms in the period when my grandparents were there. At first, I thought I would just be dealing with dissection.

No way. That was just the start of it.

There was the possibility that one of my grandparents’ body parts ended up in an anatomical museum. I wasn’t sure if I could handle that. I read an old academic paper penned by an anatomist and surgeon studying the palmaris longus and balked at a photo – was that my grandfather’s hand?

I entered a world of embalming fluid recipes, mould on bodies and bandsaws. Whereas for centuries, embalming methods were kept secret, they are now shared more freely, and sometimes adopted into a dissecting room culture when a new anatomist or technician arrives with a good mix. There are today a plethora of recipes and techniques used to embalm the dead so much so that some say the field is more craft than science. Even in death our bodies are unique – our fat or time of death means we can each react differently to the same chemical formula. I learned from the British anatomist Prof Claire Smith that mould can sometimes form on a donor through a small spore that was already there or through a student or staff member sneezing. When using a bandsaw, human heads are frozen first to get a clean line through the middle of the nose.

By going into the past, I learned about contemporary anatomy. Some students find hands freakier to dissect than faces. While in parts of the world anatomists still use bodies left unclaimed in morgues, there is also a growing “humane” anatomy movement where students meet the families of donors or hold moving ceremonies for the dead when they have finished their dissection course. I delved into the history of body donors, a curious lot who donate for all sorts of reasons, which range from being helpful to avoiding a funeral as they disliked a particular relative. Body donation tends to run in families.

Anatomists once relied on the bodies of people who did not consent to dissection – executed criminals or the vulnerable whose bodies lay unclaimed in asylums, hospitals or poor houses. Thankfully, Australia has long been considered “gold standard”: donors in the labs filled out paperwork and consented to being there. While there are no national figures on numbers of donors, the University of Melbourne, for example, gets about 200 bodies a year, some of which are shared with other institutions. Australians are still donating.

The reason body parts are flown in is fairly straightforward. Sometimes 15 knees are needed for a surgical workshop and it is logistically easier to get them from a US body broker.

After spending time with dead donors at a surgical workshop, watching dissection influencers at work on Instagram, reading evocative dissection notes from 1540 and basically becoming an amateur dissection wonk, I now have a much better sense of “what happened” to my grandparents’ bodies.

But I also know the enormous contribution that the dissected have made to medicine for the past 2,000 years or so. We are alive because of them. They should be better known in the history of science as a cohort who created a body of knowledge.

I also view my body differently. We are palaces filled with so many beautiful shapes and curves, all mirrored in nature: the leaf-like lobules in my breast, the atria centralis retinae in the eye is like a crack of lightning in the sky. I now get why some anatomists told me they enjoy dissecting. As the University of New South Wales’ Dr Nalini Pather said: “Some people do needlework, and some people do art. I like to dissect.”

And yet, will I donate my own body? Hmmmm. I’m still young. I’ve got a few years left to decide. For now, my main issue about donating my body? I imagine myself being cold in the dissecting room. I picture myself yearning for a jumper on my torso or a doona over my tattered corpse. Yes, it’s a silly line of thinking as being dead I wouldn’t feel the cold, but there you have it.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!