By Jules Murtha

Key Takeaways

- Some healthcare providers struggle to initiate and maintain end-of-life (EOL) conversations with patients due to lack of proper training.

- Aspects to consider include determining who to include in the conversation, what your goal is, when and where to have it, and how you’ll structure the interaction.

- General practitioners with experience in EOL conversations cite four important elements: preparation, finding a conversational entry point, modifying your communication to suit the individual, and inviting the family to participate if possible.

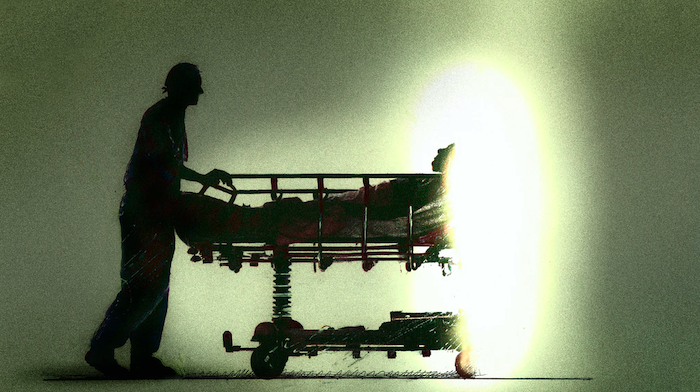

Engaging in end-of-life (EOL) conversations with patients requires careful, strategic communication on the part of the physician. For physicians and residents who lack experience covering the complex subject of death with their patients, EOL conversations can be difficult, according to a study published by the Annals of Palliative Medicine.[1]

Good physician communication, however, is central to patient satisfaction during palliative care. Residents can better prepare for EOL conversations by determining the logistics of the interaction beforehand, and tailoring their presentation to the patient’s preferred communication style.

First, focus on logistics

If you’ve yet to have your first EOL conversation in residency—or your first few—you might feel ill-equipped to start one. Even physicians who have established practices struggle to engage in such weighty interactions. Fortunately, there’s a list of questions you can answer prior to the discussion that may pave the way to meaningful results.

An AMA Journal of Ethics article explains the significance of addressing the logistical elements of an EOL conversation before starting one. [2]

These include the following:

Who? Clarify with your patient who exactly they’d like to have present for the conversation. Family members, while supportive, may disagree on treatment options or get swept up in intense emotions. It’s your responsibility as a physician to call everyone’s focus back to the patient. Patience will serve you well in EOL discussions, especially those that include family.

What? Determine what you’d like to accomplish with the conversation. Perhaps your goal is to provide updates on your patient’s prognosis, or deliver important news. On the other hand, maybe now’s the time to ask your patient what their goals of care are, or to relay that information to the family and other caregivers. You decide how much to share about the illness and its prognosis based on what your patient is ready to receive.

Where? Most often, EOL conversations take place at a patient’s bedside. This is largely due to their condition and lack of other space.

Having a quiet room free of interruptions is important for this kind of discussion. Sit near the patient rather than standing above them; this shows that you care and have time for them, and are not in a rush to leave.

When? Schedule EOL discussions when you have time to actively listen and be present for your patient. Be sure to clarify any misunderstandings, offer suggestions, and propose next steps. Try to steer clear of integrating EOL conversations into your routine rounds and office visits, as you might be too busy racing the clock to give your full attention.

How? Having a loose conversational structure may be helpful. Start by naming any goals you may have for the interaction while maintaining the flexibility your patient may require. Ask an open-ended question. Remember that your patient’s needs and ability to accept information are foremost. Listen first. This is likely to be a heavy moment for your patient, fraught with emotional upheaval that prevents them from taking in what you have to say.

“Silence can be golden in these conversations.”

— AMA Journal of Ethics

Taking cues from general practitioners

General practitioners who have had a lot of experience in palliative care conversations have developed a feel for them that can help guide residents in finding their own approach. These strategies, described in a study published by Family Practice, emphasize preparation, alongside three additional tactics to aid physicians in EOL interactions.[3]

Gauge readiness and choose an entry point

According to GPs participating in the study, successful EOL conversations are rooted in a strong patient-doctor relationship. Having already established good rapport and trust with a patient eases the EOL conversation, over and above preparing for it.

It’s important to gauge a patient’s readiness to enter into the EOL conversation. To do so accurately, you should consider the patient’s personality and psychological state.

Observe their demeanor, and pay close attention to any verbal and nonverbal cues they give you regarding their prognosis.

Once you feel you’ve got a good handle on your patient’s current state, focus on finding an appropriate conversational entry point.

There are different ways to do this, as the doctors told Family Practice. You can respond to patients’ inquiries about their goals of care, or implement EOL conversations routinely with patients who could benefit from them. For some patients, the physician might directly address their prognosis, whereas for others, it might be best to test the waters by asking indirect or hypothetical questions about plans for their future care.

Read your audience and involve the family

Two other tactics that GPs use to engage in fruitful EOL conversations are tailoring communication to the patient’s communication style and getting the family involved when it’s appropriate, as noted in Family Practice.

To better reach your patients, you may have to modify your communication style and approach the EOL discussion in increments, rather than all at once. Using a gentle approach for the patients for whom this is appropriate could mean saying something like “The chances of someone living with this for more than two years are very low.” For others, depending on the personalities of both physician and patient, and their relationship, a direct, honest approach may be the most fruitful.

Finally, the patient may choose to have family members in the room during EOL conversations. Some doctors find the presence of family to be valuable for information-sharing purposes and determining the right course of treatment for patients nearing their final days.

What this means for you

Residents who struggle with EOL conversations and discussions about goals of care may sharpen their skills in a palliative care rotation. In the meantime, prepare for EOL conversations by answering the following: Who will be present? What is the goal? Where is the best place to initiate it, and how soon?

Think about how you can structure the conversation to best meet your patient’s needs. Once you enter into the conversation, adjust your communication to a style that’s most sensitive to your patient, whether this means taking a gentler, or more direct, approach. Finally, involve the patient’s family when you feel it’s appropriate.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!