Ever since Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s book “On Death and Dying” hit the shelves in 1969, it’s been a key source of information about the grief process. Dr. Kübler-Ross outlines five stages of grief that many people go through: denial and isolation, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. But her theory was geared towards people who were in an end-of-life situation and facing imminent death. Also, she never intended the stages to be a linear timeline. Though her model is helpful for understanding grief, it has created myths about the stages of grief that don’t ring true for everyone.

Myth 1: There’s a clear timeline for grieving.

“On Death and Dying” lists five stages of grieving, but there’s no real timeline for the process. Grief is a very personal experience and most people go through it in whatever way helps them the most. You may stay in one phase longer than others, bounce back and forth between phases, skip a phase, or have phases that are uniquely your own.

The grief experience is complex and, while the five phases are a guideline, it is perfectly normal to grieve in a completely different pattern. That’s why many researchers and clinicians quit using the term “stages” when talking about grief.

Myth 2: Mourning and grief are the same thing.

This might surprise you, but they’re actually different. The definition of grief refers to the emotional state you experience when you’ve lost someone or something. Those emotions include a wide range of feelings from numbness to pain. Mourning is defined as the way you express your grief and the actions you take as you go through the grieving process. A good example of mourning is wearing black, bringing flowers to a gravesite, or following specific traditions of bereavement. Most people experience both grieving and mourning.

Myth 3: The grief process is the same for everyone.

When it comes to grieving, and even mourning, there are a lot of societal and cultural expectations about how to do it correctly. But every person is as unique as their grief process and will think, feel and act differently. Know that there is no correct way to cope with a loss. If you can find a way to grieve while feeling supported, rested, healthy, and authentic, then you are doing a great job. It won’t always be easy, but it’ll be the way you need it to be.

Myth 4: Ignoring your grief helps it go away faster.

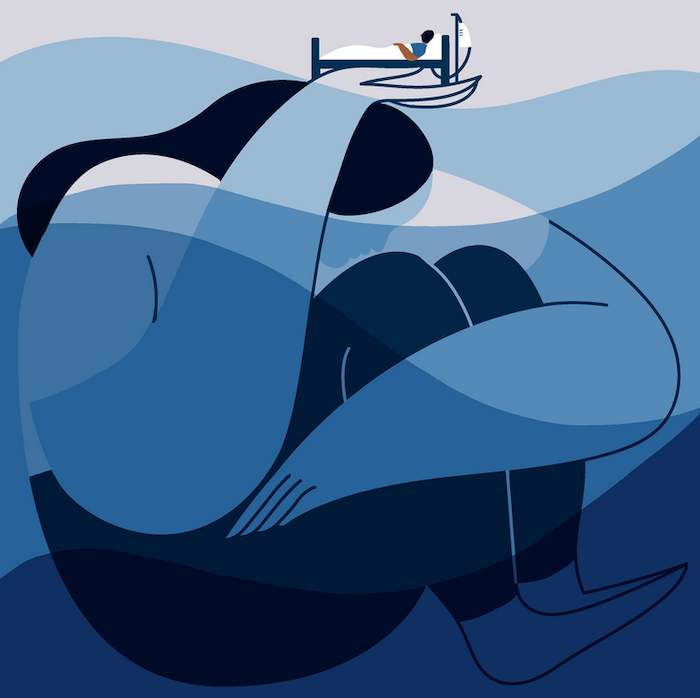

When you’re experiencing a loss, it can be tempting to stay busy and distracted. This can lead to a pattern of avoidance that keeps you from feeling your emotions and healing. Grief is emotional trauma and, like physical trauma, it’s important to acknowledge the pain and treat it.

In some cases, ignoring grief may lead people to numb their pain with substance abuse, which can cause more pain. Of course, there will be times you’ll want to take your mind off your experience. Try to find support that lets you balance some breaks with fully experiencing your grief.

Myth 5: Crying is necessary for grieving.

We grow up learning that crying is a normal response to sadness, but it’s not the only way to show you’re sad. People who don’t cry over a loss can be experiencing just as much grief as those who do. Keep in mind that feeling numb or being in a state of shock is also a common grief response. This may prevent people from expressing their emotions with tears. Crying can help you process the pain of grief, but you can still work through it without shedding a tear.

Myth 6: The first year is the toughest.

This myth is common, because it is somewhat true. The most intense emotions related to the grief process often happen in the first year. However, every year and anniversary after that may still be difficult. Remember, there is no timeline for grieving. If you are grieving or know someone who is, be open to unexpected emotions at unexpected times and don’t expect the grief process to suddenly be over. Also, remember that support groups are always available and you can get counseling services at any time, even years after your loss.

Myth 7: Grief will eventually go away.

Time does not heal all wounds, especially the wounds of grief and loss. The intensity of your grief may decrease with time, but you may never forget it or feel truly healed. Grief ebbs and flows and can continue for a lifetime. When you prepare for it to last, you may be more at ease expressing your feelings in your own way as they come and go, rather than trying to suppress or stop them. It’s also helpful to know what makes you feel better when grief shows up, so you can get the support you need.

Myth 8: The goal of grieving is closure.

Our society is built around achievement. Common milestones include graduating from school, getting married, and retiring from a career. We like to check things off the list, but closure isn’t the goal of grief. Finishing grieving is not the endgame and there is no finish line. Some say the main objective of the grieving process is to experience your feelings of loss, sadness, anger, and guilt, while taking care of yourself and continuing to live and move ahead. Keeping an open mind about grief will serve you better than looking for closure.

Myth 9: Grief affects females more intensely.

The process of grieving has taken on a lot of expectations from society, including stereotypical views of how females and males grieve. Society expects females to be more emotional, to openly grieve through crying and expressing their feelings. “Boys don’t cry” is a stereotype that keeps males from showing their sadness through tears and emotions. The truth is that every person is unique and should freely cry or not cry or show grief in their own way. No one grieves more than anyone else. We are all individual beings with individual grieving styles.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!