Would things have been better if I had known the truth?

By Lenika Cruz

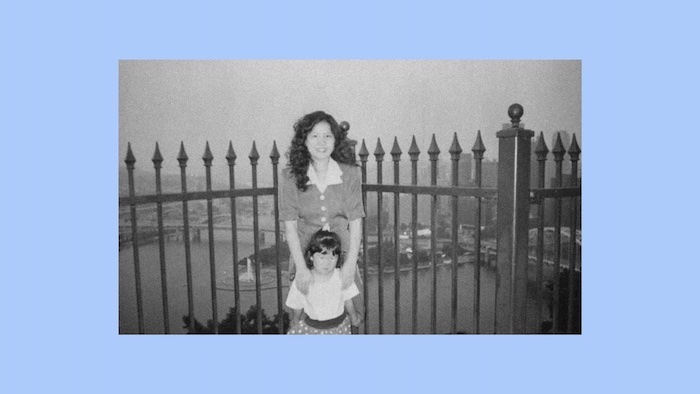

The pink notebook my mother kept when she was sick contains 18 entries, most of them shorter than a haiku. The pages list medications and surgeries, the names of family members who sent money, and which body parts hurt and how badly. One entry, from October 1995, reads: “Neck (severe pain) Coming out of the mall to cold air.” I was 5 that day; my sister was 3. We were leaving the mall after taking a family portrait when my parents started panicking—about exactly what, I didn’t know. I just remember my dad rushing my mom home because of what I later learned was an excruciating neck spasm. Hours later, an ambulance took her to the hospital for the last time. Four months later, she was gone.

One strange thing about losing a parent so young is that you might forget which details you learned about their death and when; you might also question whether what you remember is the truth or a distortion. At some point during the first decade of my life—I’m not sure when or how—I became aware that my mom had died of breast cancer. Last month, I asked my father how much my sister and I knew about our mother’s illness at the time, if we understood that we might soon lose her. “I don’t know if we ever told you,” he admitted. “Your mom wanted to shield you both from that stuff. She always wanted to protect you.” I figured, then, that we had learned the truth from overhearing conversations between the grown-ups around us—and I wondered whether it would have been better if we had known before she passed.

What should you say to a child when a parent is dying? The answers to this impossible question generally fall into two buckets: Tell them the truth or protect them from the truth. The most persuasive arguments in either direction prioritize what would be best for the child. My colleague Caitlin Flanagan wroteabout why she and her husband told their then-5-year-old sons that she had breast cancer: “I thought I had the power to protect them from hardship. No one has that … But endurance is built into the human condition, and it’s as powerful in children as it is in adults.” In a 2019Atlantic essay, Jon Mehlman explained why he and his wife chose not to tell their three young daughters about her cancer for seven years—until a month before her death: “Our kids would not be robbed of stability; protecting their sense of the ordinary was everything.” Later, his daughters told him they were grateful not to have known for so long.

Reading these accounts, I felt conflicted about my own experience. I hadn’t known my mom’s diagnosis, and no one explained to me what a mastectomy or chemotherapy was, but I witnessed plenty of signs that she was declining. I saw her without her wig after all her hair fell out. I knew that she sometimes didn’t feel well, and I would visit her in the hospital, where I’d push her wheelchair and play with the automatic-recline button on her bed. I understood during those dark months that things weren’t normal, but I still remember myself as a happy child. I know now that memories can be faulty, and I wonder if it’s truly possible for a child surrounded by so much evidence of suffering—and denied the full truth about that suffering—to emerge from that experience unscathed.

Was I simply too young to understand mortality? Linda Goldman, a grief counselor and the author of several books on children and loss, told me that, contrary to what many adults believe, small children are not too young to feel sad about death. “Kids can love when they’re toddlers, and they can grieve. They’ll cry when a goldfish dies!” she said. And when it comes to a parent’s illness, Goldman explained, children are more perceptive than many adults give them credit for: “Kids are pretty savvy, and they take in what’s going on in their environment even if they’re not told the truth.”

While she acknowledged that the question of preparing children for loss has “no black-and-white answer,” she does recommend being honest about a loved one’s illness or death in an age-appropriate way. That’s because when children sense that they’re being lied to, Goldman said, they can start to fear for their safety and become distrustful. I told her that I had been wondering whether my parents were wrong not to have prepared me and my sister for my mom’s death, and whether I wasn’t really as happy as I remembered.

But the more we talked, the more I realized that fixating on a binary question—to tell children or not tell them?—obscures the many other factors that shape how a child will process loss. For instance, Goldman explained how having a memory of helping a dying family member—giving them flowers, bringing them medicine, making them laugh—can make children feel useful, and be an enormous psychological comfort. I thought of how one of my strongest memories of my mom’s illness is helping her reverse the car when she was driving. By that point, the cancer had spread to her lymph nodes and turning her neck hurt, so I would look back for her and let her know whether the coast was clear.

So much, too, depends on the ability of adults to cope with the situation. “I’ve found that kids can handle what adults can handle,” Goldman said, noting that children look to grown-ups for emotional cues. When we spoke recently, my dad told me something I had never known before: that back then, even hehadn’t truly believed that his wife might die. He had always thought that she would pull through somehow. Perhaps that naïveté or stubborn faith—whatever you want to call it—had the unintended consequence of shielding me and my sister. Goldman also said that when parents are struggling, children need to have adults around them whom they know they can depend on. While my dad was balancing a full-time job with helping to care for my mother, my mom’s parents came to stay with us and looked after me and my sister. At no point did we have to feel abandoned or alone.

Being able to say goodbye—whether before or after a parent dies—is crucial as well, Goldman said. Even though I didn’t know that my mom was nearing the end, I was at the hospital all the time during her final weeks. And hours after she passed, according to my father, I took him by the hand and led him toward her hospital room. Then I crawled into the bed next to her and started touching her face and talking to her, even though she could no longer respond. A week later, at her funeral, my sister and I stood next to her coffin the entire time. Sometimes, Goldman said, adults want to keep children away from funerals and other rituals of loss: “We’re so death-phobic that it’s hard to admit that death is a part of life.” But these moments can offer valuable opportunities for closure, even if the search for answers and feelings of loss never quite go away.

When I called Goldman, I was half-expecting her to tell me all the ways I must have remembered something incorrectly, to point out the holes in my story. Instead, she gave me a deeper appreciation not only for what my parents had to go through, but also for the ways in which my 5-year-old brain had allowed me to come away from that painful time carrying warmly lit scenes of my mother: Even with IVs coming out of her, with a terry-cloth cap keeping her bare head warm, she looked so pretty laughing.

Somehow, when my parents made what some therapists might call mistakes, the results still had a certain beauty to them. Goldman said adults should be careful with clichés about death, such as telling young children that someone who is dying is simply “going to sleep” or that they will be “watching over you all the time.” Kids might take these words literally and become afraid of sleeping or worry about being surveilled. Like many other children, I was told that my mother would be “watching me from up in heaven,” a place I understood only as being somewhere in the sky. Two weeks after she died, we flew back to Guam, the island where my parents first met, where we would bury her. I had the window seat. Staring out over the left wing of the plane, I searched for her among the clouds

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!