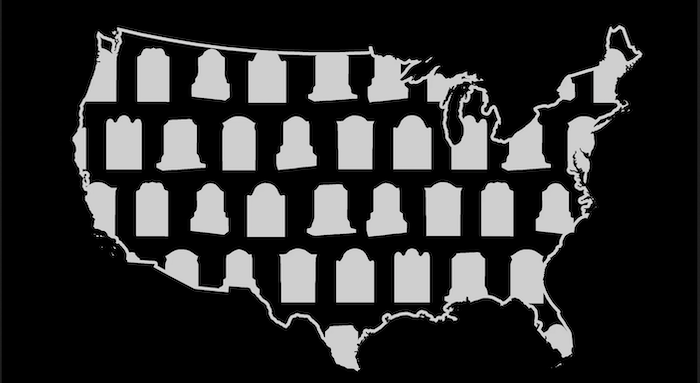

The pandemic has forced many to rethink and readjust their present with their future. Some have left jobs that provided steady paychecks and a predictable complacency for unknown, yet meaningful passion projects. Others are are taking more control of their destinies as they see fit. Unwilling to settle in life anymore. So why would you settle in death?

That’s the question Kathy Benjamin, author of “It’s Your Funeral! Plan the Celebration of a Lifetime — Before it’s Too Late,” asks. Amid the book’s 176 pages, Benjamin exposes readers to death in a light, humorous, and practical way, akin to a soothing bath, rather than a brisk cold shower.

The Austin-based writer’s niche is death (her last book centered on bizarre funeral traditions and practices). Having panic attacks as a teen, Benjamin said enduring them felt like she was dying. It was then that she started wrestling with the idea of death.

“I feel like I’m actually dying all the time, so maybe I should learn about the history of death and all that,” she said. “If I’m going to be so scared of it, I should learn about it because then I’d kind of have some control over it.”

It’s that control that Benjamin wants to give to readers of this book. She introduces readers to concepts and steps one should contemplate now, in order to make sure the last big gathering centered on you is as memorable as you and your loved ones wish. Poring over the book, one finds interesting final resting options such as body donation that goes beyond being a medical cadaver, “infinity burial suits” that lets one look like a ninja at burial, but also helps nourish plants as decomposition begins; and quirky clubs and businesses that allow one to make death unique (as in hiring mourners to fill out your grieving space and time, and designing your own coffin).

Now before you think this is all a bit macabre, Benjamin’s book also serves as a personal log so you can start planning your big event. Amid the pages, she offers prompts and pages where you can jot down thoughts and ideas on fashioning your own funeral. If you want to have a theme? Put it down in the book. You want to start working on your eulogy/obituary/epitaph, will, or your “final” playlist? Benjamin gives you space in her book to do so. It’s like a demise workbook where you can place your best photos to be used for the funeral and your passwords to your digital life, for your loved ones to have access to that space once you’re gone. If all the details are in the book, a loved one just has to pick it up and use it as a reference to make sure your day of mourning is one you envisioned.

As Benjamin writes: “Think about death in a manner that will motivate you to live the best, most fulfilling life possible. By preparing for death in a spiritual and physical way, you are ensuring that you will succeed right to the end.”

“Everyone’s going to die, if you’re willing to be OK with thinking about that, and in a fun way, then the book is for you,” she said.

We talked with Benjamin to learn more about the details of death and thinking “outside the coffin” for posterity’s sake. The following interview has been condensed and edited.

Q: How much time did it take you to find all this data about death? You share what was in the late Tony Curtis’ casket.

Kathy Benjamin: I have shelves of books that range from textbooks to pop culture books about death, and it’s something that a lot more people than you think are interested in so when you start doing online research you might just find a list of, here’s what people have in their coffin and then from there, you’re like: ‘OK, let’s check if this is true.’ Let’s go back and check newspaper articles and more legitimate websites and things and those details are out there. People want to know. I think of it as when you see someone post on Facebook — somebody in my family died. I know for me, and based on what people reply, the first thing is: What did they die of? We want these details around death. It’s just something people are really interested in. The information is out there and if you go looking for it, you can find it.

Q: Was the timing for the release of the book on point or a little off, given the pandemic?

KB: That was unbelievable timing, either good or bad, how you want to look at it. I ended up researching and writing during that whole early wave in the summer (2020) and into the second wave, and it was very weird. It was very weird to wake up, and the first thing I would do every morning for months was check how many people were dead and where the hot spots were, and then write … just a lot of compartmentalization. My idea was because people who were confronting death so much, maybe it would open up a lot of people’s minds who wouldn’t normally be open to reading this kind of book, they’d be like: ‘OK, I’ve faced my mortality in the past year. So actually, maybe, I should think about it.’

Q: Is there anything considered too “out there” or taboo for a funeral?

KB: I always think that funerals really are for the people who are still alive to deal with their grief, so I wouldn’t do anything that’s going to offend loved ones. I can’t think of what it might be, but if there’s a real disagreement on what is OK, then maybe take the people who are going to be crying and keep them in mind. But really, it’s your party. Plan what you want. There are so many options out there. Some people, they still think cremation isn’t acceptable. Because death is so personal, there’s always going to be people who think something is too far, even things that seem normal for your culture or for your generation.

Q: You mention some interesting mourning/funeral businesses, but many seem to be in other countries. Do we have anything cool in the U.S. as far as death goes that maybe other places don’t have?

KB: One thing we have more than anywhere in the world is body farms. We have a couple and just one or two in the entire rest of the world. The biggest in the world is at the University of Tennessee. For people who don’t know, body farms are where you can donate your body as if you would to science, but instead of doing organ transplants or whatever with it, they put you in the trunk of a car or they put you in a pond or they just lay you out and then they see what happens to you as you decompose. Law enforcement recruits come in and study you to learn how to solve crimes based on what happens to bodies that are left in different situations. I think they get about 100 bodies a year. I always tell people about body farms because if you’re into “true crime” and don’t care what happens to you and you’re not grossed out by it, then do it because it’s really cool and it’s helpful.

Q: You mention mummification and traditional Viking send offs, what about the burning of a shrouded body on a pyre? Have you heard about that? It was the way hunters were sent into the afterlife on the TV series “Supernatural.”

KB: I haven’t heard of anyone doing it in America but obviously that’s a big pop culture thing. For Hindus, that’s the way it happens in India … you go to the Ganges, and they have places specifically where you pay for the wood and they make a pyre and that’s how people go out. I doubt there’s a cemetery or a park that would allow you to do it in the U.S., but on private land, you’re pretty much allowed to do whatever. I would definitely check on regulations. You would have to get the pyre quite hot to burn the body to ash, like hotter than you think to make sure you don’t get a barbecued grandpa.

Q: In your research, have you come across anything that completely surprised you because it’s so unheard of?

KB: There’s been things like funerary cannibalism, which is where you eat loved ones after they’ve died. But once you’ve read the reasons why different tribes around the world have done it, you’re like ‘OK, I can see why that meant something, why it was meant to be emotional and beautiful.’ Things like sky burial in Tibet, they have a Buddhist monk chop up the body and lay it out for the vultures to come get. Part of it ties back to Buddhist tradition but also it’s Tibet, you can’t dig holes there in the mountains. So, there’s a logical reason for it. When you look at these things that originally seem gross or weird, once you learn the reasons behind them it all comes back in the end to trying to do something respectful for the dead, and trying to give the living that closure.

Q: What are your plans for your funeral?

KB: I definitely want to be cremated. I don’t know if I want people to necessarily come together for a funeral for me but like I have a playlist, and even before the book I had a whole document on the computer of what I wanted. I want all the people to know about the playlist and then they can kind of sit and think about how awesome I am while the sad songs play, and then there’s different places that I would want my ashes scattered.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!