By Jack Cameron Stanton

FICTION

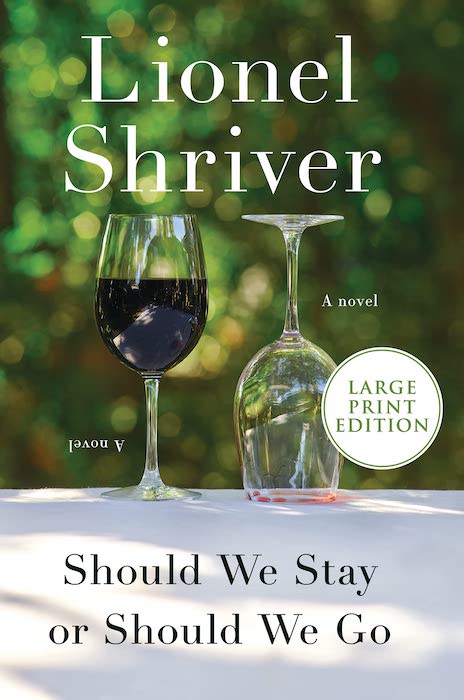

Should We Stay or Should We Go

Lionel Shriver

Borough Books, $29.99

Is life, no matter its quality, sacrosanct? In 2018, Aurelia Brouwers, a 29-year-old girl, caused controversy by ending her life legally in the Netherlands. Her case was anomalous: she did not suffer from a terminal illness, rather struggled with a history of mental illnesses, suicide attempts, self-harm and psychosis.

Assisted-dying remains a fiercely contested area in global euthanasia laws, belonging to the interdisciplinary branch of ethical discourse known as bioethics, which debates the value of human life. With the advances in modern medical knowledge, the global average life expectancy has increased to 72.6 years, up from 65.3 in 1990, as estimated by the United Nations.

And the transhuman movement, which advocates the research and development of human-enhancement technologies, theorises that near-future breakthroughs will extend human lifespans indefinitely.

In Should We Stay or Should We Go, Lionel Shriver, best known for We Need to Talk about Kevin, confronts the issue of assisted-dying and euthanasia when her protagonists Kay and Cyril Wilkinson propose “that we get to 80 and then commit suicide”. They are not suffering unbearably when they make the decision; in fact, they’re in their mid-50s, and in excellent health. Their reasoning is simple: humans were never meant to live beyond 80, and they ought to die on their own terms, before they succumb to the entropy of their biological clocks on borrowed time.

The novel’s departure point is March 29, 2020 – the day of Kay’s 80th birthday. After the “giddy, mind-racing rush to capitalise on time remaining”, the world has unexpectedly changed. Brexit reignited Cyril’s fierce anti-leave sentiment, and coronavirus turned Britain into a ghost land. As a result, Kay and Cyril appraise the lethal pills before them and begin to soliloquise about death in a corollary of Hamlet’s “to be, or not to be”. Problem is that as octogenarians, they remain in good health, not the mindless or stupefied walking corpses they feared they would become.

From here, Shriver disrupts the narrative with multiple scenarios that imagine what Kay and Cyril do next. Using this non-linear structure, Shriver creates a novelistic thought experiment, a network of possibilities, with each chapter reverting in time to choose a different path.

Kay goes ahead, Cyril backs out, and soon has a stroke that imprisons him inside his own body. Advances in medicine produce a magic pill that reverses ageing and allows people to live at optimal youth indefinitely. Their children, aghast that their parents planned suicide, and had squandered their inheritance, subject them to a cruel assisted-living home. Kay succumbs to dementia, and her family grieves as if she’s already dead.

For a while, banal subplots and dialogue about the burden the old place on Britain’s health system ride the coattails of a clever structural design. Cyril finally gets around to penning his memoirs, in which he writes at length about Brexit, the NHS, and why any responsible person should end their own life before becoming “fiscally ruinous”.

Kay and Cyril die many times, but never die. Each chapter resurrects them at a particular point in the preceding narrative and allows them to choose a different path. The result is that we feel trapped in a time-warp, reliving moments ranging from the banal to the dramatic. There’s something cavalier, even irresponsible, about the idleness with which Kay and Cyril discuss their exit plan, as beholden to a kind of botched utilitarianism, in which their deaths will alleviate the strain on a healthcare system clogged by senescent bed-hogs.

For me, euthanasia or assisted-dying becomes a complex moral dilemma when the person who wants to die is experiencing unceasing, terminal, and/or unbearable pain in life, and wishes a dignified death that involves a physician’s help. Stripped of this urgency, Kay and Cyril seek to end their lives merely to escape middle-class malaise, and this lack of high stakes, combined with a structure that relies on iteration, undermines the perspicuity its protagonists aim to convey.

What’s more, the structure, at first nifty and whimsical, soon wearies, and the result is an uroboric cycle during which every death is hypothetical, every decision temporary.

Should We Stay or Should We Go promises to explore mortality at a time when growing technological capacity to keep people alive has stretched the “sanctity of life” ethic to the verge of collapse. Although the premise compels, Shriver’s novel is weighed down by the snobbish longueurs of two well-off oldies who, despite their fears of death and dying, find their immortality by coming back to life chapter after chapter.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!