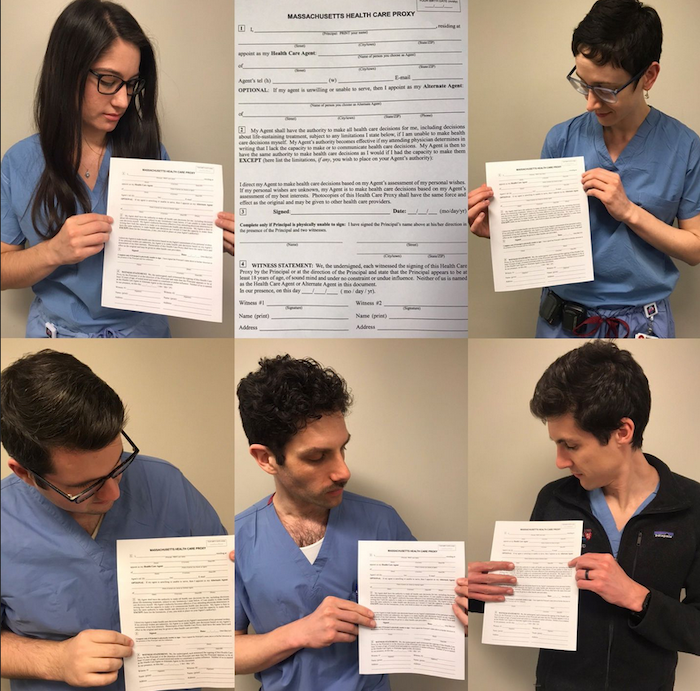

Robbed of obsequies for those we love adds an unconscionable burden

By

The famous spiritual writer Henri Nouwen, as a young man back-packing through Ireland, watched a burial in Donegal, fascinated by a group of men filling in a grave as the grieving family watched in silence.

What struck him was the way, when the task was almost complete, the men used the backs of their shovels to tap down the clay. The ritual, he felt, was saying to the bereaved: “This person is dead, really dead. There is no doubting now this obvious truth.”

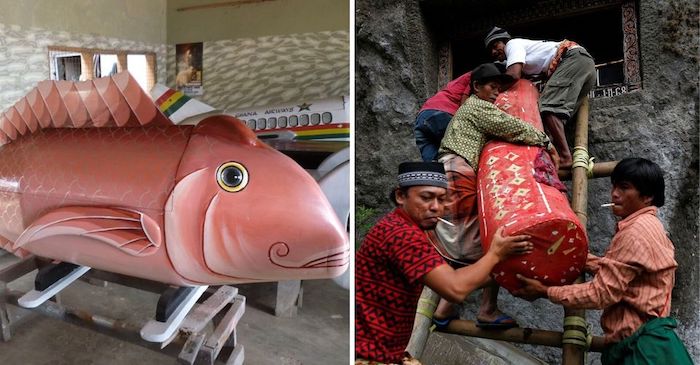

In recent years the ritual of filling in the grave is not as common as heretofore but, as with other rituals, we often don’t aver to the purpose behind them, or why they developed. They are part of a pattern, a background against which we measure our way of dealing with death.

When death occurs in Ireland, we move effortlessly into funeral mode. There’s a familiar template for family, community and necessary services

Strangely, for some like Nouwen from other cultures, they are signposts of a comfort zone that in faith and in family we have successfully created around the difficult experience of grieving those we love.

We are a funeral people. Funerals, unlike in some other cultures, are huge events in Ireland. A friend told me once about working in an office in Scandinavia when a colleague broke down at work. It emerged that he had buried his mother that morning and was back at work that evening.

It would be unthinkable, unimaginable, even shocking in Ireland.

When death occurs in Ireland, we move effortlessly into funeral mode. There’s a familiar template for family, community and necessary services. It’s a kaleidoscope of respect, mood, attitude, support systems and rituals that resonate with the need to create a platform for dealing with such an earth-shattering experience.

Community support

A key element is support offered by the community. People gather and individually offer their condolences. It may be no more than a brisk shake of the hand and a cliched formula of words but it’s fundamentally about respectful presence in solidarity with the grieving.

The coronavirus has robbed us of many things but the experience of dealing with the death and funeral obsequies of those we love adds an unconscionable burden at the present time.

Grieving brings with it a variety of responses, some reasonable to the outside observer, others part of the blame game we play to lessen the pain of loss

Stories emerge of family members watching from the distance as a loved one faces into what must be the loneliest experience of all and not be able to hold a hand or give a hug or a kiss seems almost beyond human endurance.

A wife, now a widow, told a newspaper about how she had expected her husband to die at home and how she might have lain beside him to comfort him in his dying but their last moments together were supervised by health authorities as she watched him through a window.

Rites and rituals

The other, added weight to bear for the grieving is to be deprived of the comfort and consolation of the rites and rituals of a funeral. At present only 10 people can attend a funeral Mass or a graveside and are expected to follow the rules about social distancing.

And the community response is limited to neighbours and friends sitting in their cars outside the church or in towns, lining the streets as a mark of respect. Interestingly the Government, knowing the limits to human endurance and the place burying the dead has in our culture, didn’t seek to ban funeral Masses.

Grieving brings with it a variety of responses, some reasonable to the outside observer, others part of the blame game we play to lessen the pain of loss. If a priest, undertaker or doctor gets it wrong at the time of our funeral it becomes an enduring family memory that festers for years.

With death and dying, the ground we stand in is a sacred space.

That said, our obligation to the living has to take precedence. In boring but necessary repetition, the warnings keep coming from the authorities – social distancing, hygiene etiquette, stay at home – and they need to.

The sun may be shining but the journey towards the promised land of something approaching normality is far from over. And if grieving families have to accept the present difficult arrangements around death and funerals, the rest of us should be prepared to accept our more marginal sacrifices.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!