An interview with Syd Balows

By Rebecca Yaffe and Maggie Watson

Our monthly column addresses the same set of questions regarding advance planning and end-of-life care to a variety of people in our community. Our intention is to generate discussion as well as collect information by exploring this one theme seen through multiple perspectives. Possibly we can develop a vision and next steps for our community!

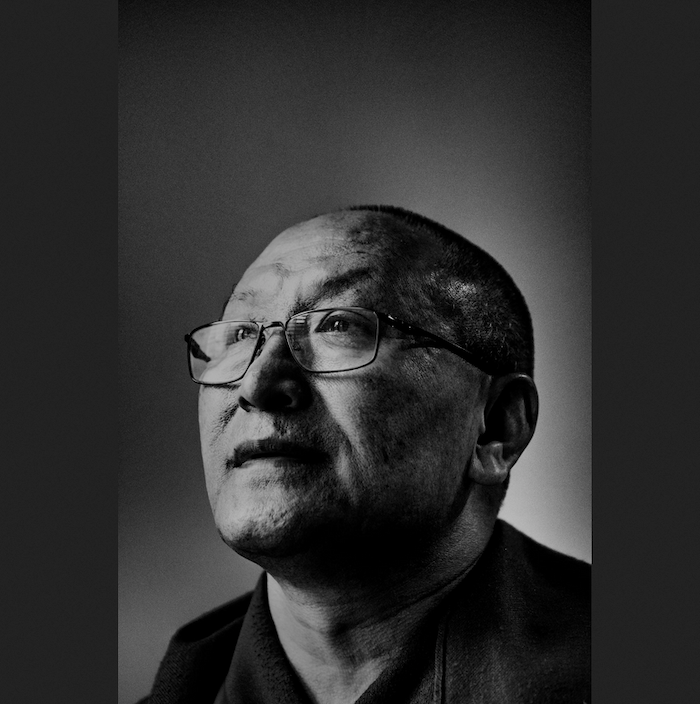

This month’s interview is with Syd Balows who has lived at The Woods Retirement Community in Little River since 1999. He is active as a real estate broker selling homes only in The Woods. He is a charter member of the Death and Dying Group, which started in 2012 with 15 active members. In the Death and Dying group, there have been eight graduates and they all have received Gold Stars. Our current group ranges in age from 67 to 99 years old.

• In your experience in this community and your profession: What has been successfully advanced planning for?

Taking care of business! The 6 Ps says it all: Prior Planning Prevents Piss Poor Performance.

Our friend Sunny was also a founding member of the Death and Dying Group. She planned her dying process. She used VSED (Voluntary Stopping of Eating and Drinking). I spent time with her every day as she was going through the process of dying. Sunny had a list of 18 people she wanted to call and say goodbye to. I would dial the number and then hand the phone to Sunny. She would say, “Hi, I just called to say goodbye because I’m leaving this planet. You have always been such a kind friend to me.” Often times we were holding hands as the tears flowed as she was saying goodbye to her many friends.

Sunny made previous arrangements with a home funeral facilitator. Sunny had chosen to have a Celebration of Life party in her living room. Her cardboard casket was on a table awaiting decorations and wishes for a safe journey. She had a green burial in Caspar Cemetery.

When you make your own decisions you take the burden away from someone else. Be as detailed as you can be to avoid resentment with family members. Many siblings never talk to each other again because of resentments. Think clearly about what you give your beneficiaries. I have seen the men in the family get the business and the women get the furniture.

• What gaps do you see in advanced planning?

Honesty – being truthful about inheritance. If the dying elder changes their mind about who the family executor will be and doesn’t share that change with the family, the results can be a family breakup.

For example, David was told by his parental unit he would be the executor of their estate. The parental unit changed their minds about which sibling was going to be executor. They chose the oldest daughter, RN Ann, to be executor and daughter, RN Laura, to be co-executor. The parents signed all the right forms to make the change of executors but didn’t tell David that he was relieved of his duties. The elders didn’t want a conflict. He was really pissed!

Laura took care of Mom every weekend for four years. After Laura reached burnout, she asked Ann to become the new caregiver. Ann quit her job at the VA, moved out of her home into a suitable rental on the river and became the POA – power of attorney – for health care until the end of Mom’s life, four years later.

David and his sisters disagreed about whether they were to be paid caregivers for their parents, or if they were supposed to donate their time to the estate as co-executors. Because there was nothing spelled out in the legal documents that addressed these issues, it caused a family conflict.

• What have you seen work about end-of-life care?

Acceptance. Accept the things I can’t change. Change the things I can.

Community works. Like-minded people sharing space as we age “right on schedule.”

“Neighbors helping neighbors.” My dying group has had many graduates. We all got to help each other through the process and that has been great for our group. Get the paperwork done to say what you want it to say. “Say what you mean and mean what you say.”

• What gaps do you see in end of life care?

Our local medical system is not very dependable. The fate of the hospital and its chance of survival is having a huge impact on people moving here and people wanting to move away. We have a rural hospital that, to survive, must have an affiliation with a larger hospital group with deeper pockets. We need to have a Medicare-approved hospice, rather than our previous volunteer hospice. A Medicare hospice will serve the community better.

Real estate sales in The Woods in Little River has decreased because elders do not want to live in a community without medical service and a viable hospital. Election years are always bad for real estate.

Recruiting staff for the hospital is difficult for the same reasons that people do not want to commit to coming here if they do not know if their jobs are permanent. But people who live on the coast accept the fact that they will have less in the way of medical care than someone living in a city and plan accordingly. We know that we have to travel for care.

Elder financial abuse is rampant. I have heard of family caregivers removing jewels, a granddaughter set up a meth lab in an elder’s home, changed bank accounts into her name and brought in friends to live freely. There is no return of funds lost.

Many surviving spouses do not know how to deal with household finances. They need help or to have someone in charge to go through this phase. If the spouse who does know does not share the information, it is almost tragic because you have left that person paralyzed.

• Is there anything else you would like to add?

The aging process takes place every day and is frequently life-altering. It is a loss that you can no longer do today what you could do yesterday and that could be frightening. The quality of life is way more important to me than the quantity of life. Healthy aging requires acceptance of the reality of the living and dying process. Birth and death are the natural evolution of coming and going.

Death isn’t that bad a thing, because afterward there has never ever been even one single complaint.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!