In life, we strive to reduce and reuse. The human composting center Recompose aims to offer a more sustainable death.

by Lilly Smith

What happens to us when we die? It’s one of life’s most enigmatic and profound questions. And—let me clear this up now—I don’t have any insights to offer on the afterlife. But the first renderings of new after-death center Recompose (don’t call it a “funeral home”) reveal another option for the afterlife of our bodies here on earth: composting.

The flagship facility, expected to open in Seattle in spring 2021, is designed to reconnect human death rituals with nature and to offer a more sustainable alternative to conventional burial options. Today, burial often involves chemical-laden embalming, while cremation uses eight times more energy, according to the architects at Olson Kundig who designed the new facility. Recompose will offer a first-of-its-kind “natural organic reduction” service on-site, which will “convert human remains into soil in about 30 days, helping nourish new life after death.”

Recompose emerged as an idea in 2016—the result of a Creative Exchange Residency at the Seattle-based global design practice that brought Recompose founder and CEO Katrina Spade and her team into collaboration with the architects to create a prototype facility.

But the passage of a new bill “concerning human remains” in Washington State has quickly ushered their prototype into the realm of the possible. After Governor Jay Inslee signed SB-5001 this past May, Washington became the first state to recognize “natural organic reduction” as an alternative to cremation or burial. The law will go into effect May 1, 2020, according to the Seattle Times.

With the design of Recompose, the architects at Olson Kundig have brought a whole new meaning to the term “deathbed.” Their design for the facility is focused on a few key aspects of the experience, starting with the individual “vessels” where the organic reduction takes place. In typical funerary practice, they might be referred to as coffins; a person’s remains are placed in the vessel and covered with woodchips. There, the remains are aerated to create a suitable environment for thermophilic bacteria, according to Dezeen. That bacteria will then break the remains down into usable soil.

What’s the benefit of this process taking place in a controlled facility like Recompose, as opposed to a cemetery? “By converting human remains into soil, we minimize waste, avoid polluting groundwater with embalming fluid, and prevent the emissions of CO2 from cremation and from the manufacturing of caskets, headstones, and grave liners,” the company explains on its website. What’s more, it explains, “By allowing organic processes to transform our bodies and those of our loved ones into a useful soil amendment, we help to strengthen our relationship to the natural cycles while enriching the earth.”

Seventy-five of these individual spaces will be built as part of the first Recompose project. They’re arranged to surround a large, airy gathering space at the center of the 18,500-square-foot facility. This space will be used for services, and reads more New-Age health center than macabre funeral parlor: It’s bright and light-filled, punctuated by trees, and canopied by tall natural wood ceilings.

“This facility hosts the Recompose vessels, but it is also an important space for ritual and public gathering,” says Alan Maskin, principal and owner of Olson Kunig. “The project will ultimately foster a more direct, participatory experience and dialogue around death and the celebration of life.”

Although Recompose claims to be the first facility to offer organic reduction services, Recompose is not alone in trying to end the practice of keeping death and its associated after-care rituals at arm’s length—a movement that’s come to be known as “death positivity.”

Caitlin Doughty is one such person working in this space. She is the co-owner with Jeff Jorgensen of Clarity Funerals, which offers environmentally-friendly services like carbon neutral cremation, tree planting memorials, all natural products, and locally produced urns and caskets. Doughty is also the founder of the Order of the Good Death, “a group of funeral industry professionals, academics, and artists exploring ways to prepare a death-phobic culture for their inevitable mortality.” She had previously founded Undertaking LA, which Tara Chavez-Perez, a publicist for the Order of Good Death, said shut down earlier this year.

According the website, the business was an “alternative funeral service” that brought people closer to the experience of death by “placing the dying person and their family back in control of the dying process, the death itself, and the subsequent care of the dead body,” for instance by helping people take care of a loved one’s corpse at home. Undertaking LA offered more sustainable alternatives to typical practice as well, including biodegradable willow caskets, according to the New Yorker.

She also sits on Recompose’s board—and, as Chavez-Perez told me, “Caitlin’s an enthusiastic and avid supporter.”

New alternative burial companies (like the startup Better Place Forests, which sells the right to scatter your ashes beneath a redwood) are trying to bring nature back into the commercial funeral industry. Recompose, meanwhile, is trying to use nature as the framework for a better death. “We asked ourselves how we could use nature—which has perfected the life/death cycle—as a model for human death care,” Spade says in a statement. “We saw an opportunity for this profound moment to both give back to the earth and reconnect us with these natural cycles.”

With Recompose, Olson Kunig has designed a seemingly more sustainable alternative to burial or cremation—and perhaps a small way for you to leave the world better than you found it.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

On the art of dying

By Gary Moore

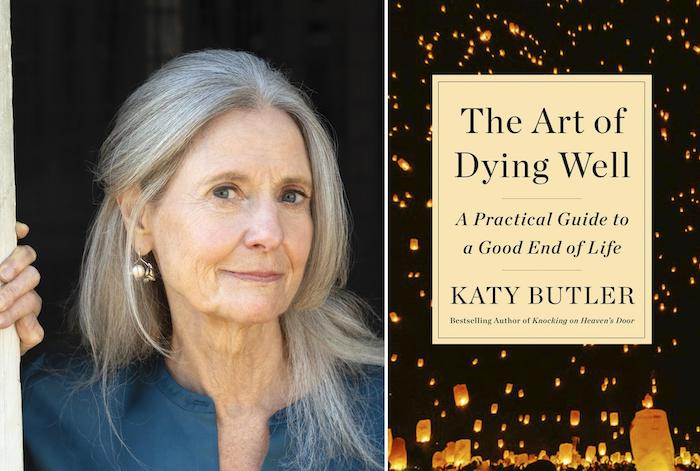

I’m reading this excellent book by the author Katy Butler entitled “The Art Of Dying Well.”

Put down those phones, no emergency call needed! I’m not going anywhere for awhile. I just want to be prepared.

George Harrison, one of my musical idols also spoke a lot about preparing for death, so when you finally die, you can do so peacefully and transition seamlessly into the next stage of your life. In fact, he wrote a song entitled “The Art of Dying,” which appeared on his first solo album “All Things Must Pass.” In that song, he wrote:

“There’ll come a time when all your hopes are fading

When things that seemed so very plain become an awful pain

Searching for the truth among the lying

And answered when you’ve learned the art of dying”

George’s wife, Olivia, said that when he passed, you didn’t need a candle to light the room. By that, I assume she meant his lighted spirit left his body. Selfishly, I wish George hadn’t left so soon, and I doubt I will encounter him if he returns (because he may not, having died peacefully). But, one never knows.

George’s wife, Olivia, said that when he passed, you didn’t need a candle to light the room. By that, I assume she meant his lighted spirit left his body. Selfishly, I wish George hadn’t left so soon, and I doubt I will encounter him if he returns (because he may not, having died peacefully). But, one never knows.

In the book, Ms. Butler outlines chapter by chapter what elders can do as they reach the end of their life cycle and how to prepare for each stage. She thoughtfully begins each chapter by stating “If you are experiencing…” and lists several conditions, going from mildly annoying to life-threatening, that people our age will experience as they reach the end. It’s done matter of factly, clinically, but with great warmth and compassion, because she then expounds in each chapter on what you should be doing at each particular stage.

One of her suggestions that I found very helpful was transitioning from a general practitioner to a doctor that specializes in elder medicine. In this kind of practice, the doctor asks “What is it that you want to do?” rather then tells you how she or he is going to save you from dying.

Let’s face it: death is a phase we all must go through. There may be a way to delay it, preventative practices you can use to slow it down, but, in the end, it’s the end.

A reader recently responded to one of my articles that discussed death with a quote from the film director and gay rights activist Derek Jarman, who is quoted to have said “I am not afraid of death, but, I am afraid of dying.”

This is because, we know death is coming, but we don’t know how or when it will come. We are unsure of the process by which we transition from life to death and what waits on “the other side.” We have books on faith and religion and spirituality to suggest, in some way, what we might expect, but we don’t know for sure and that uncertainty breeds fear.

On the other hand, another of my heroes, Mark Twain, is quoted as saying “The fear of death follows from the fear of life. A man who lives fully is prepared to die at anytime.”

A story told about St. Francis of Assisi has a man asking everybody in town what they would do if they knew they were going to die tomorrow. Various people offer various versions of tying up loose ends. When the man reaches Francis, Francis is hoeing the garden of the monastery. The man asks Francis what he would do. Francis looks up and around, smiles and replies “I would keep hoeing.”

I doubt that I possess Francis’ courage, strength of faith or ease with mortality. In fact, I might add, this column seems to verify that. Dylan Thomas urges us to “rage / rage / against the dying of the light.”

Katy Butler urges us to accept it and prepare for it as best we can.

I find myself somewhere in the middle. As my younger friend expressed it “I have so much more I have to do.” I think many people in my generation feel that way. Places to go. People to visit. Grandchildren to watch grow. Alas and alack.

But, in conclusion, this quote from Lord Beaverbrook, who was a newspaper tycoon and member of Churchill’s cabinet, struck me:

“This is my final word. It is time for me to become an apprentice once more. I have not settled in which direction. But, somewhere, sometime, soon.”

The idea of becoming an apprentice, of starting over, of beginning a new, different phase of “life” appeals to me. And, maybe, that’s exactly what happens.

Or, to quote Oscar Wilde’s dying words: “Either that wallpaper goes, or I do.”

He did.

Hold those grey heads up!

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

South Koreans Take Part in ‘Living Funerals’ to Improve Lives

by Bryan Lynn

Thousands of South Koreans have taken part in “living funeral” services in an effort to help improve their lives.

The experience is designed to simulate death for individuals seeking to increase their knowledge about their current lives.

More than 25,000 people have completed mass “living funerals” at the Hyowon Healing Center in Seoul since it opened in 2012.

“Once you become conscious of death, and experience it, you undertake a new approach to life,” said 75-year-old Cho Jae-hee. Cho took part in a living funeral that was part of a “dying well” program offered by her local community center.

The event was attended by many people from the area, both young and old. During the program, people are asked to lie down in a closed coffin for about 10 minutes. They can also write a will and take funeral pictures.

University student Choi Jin-kyu also took part in a “dying well” event. He told Reuters news agency the experience helped him realize that, too often, he considers others as competitors.

“When I was in the coffin, I wondered what use that is,” the 28-year-old said. Choi added that he now plans to start his own business after finishing school instead of trying to enter the highly-competitive job market.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, has rated South Korea 33 out of 40 countries on its Better Life Index. The index considers many measures of personal well-being, including housing, income, employment and health.

Many younger South Koreans have high hopes for education and employment. But such hopes can be ruined because of economic conditions.

Professor Yu Eun-sil is a doctor at Seoul’s Asan Medical Center who has written a book about death. “It is important to learn and prepare for death even at a young age,” she told Reuters.

In 2016, the World Health Organization reported South Korea’s suicide rate was 20.2 per 100,000 people. That is nearly double the worldwide average of 10.53.

Hyowon Healing Center began offering living funerals to help people see the value in their current lives. The experience can also help people seeking forgiveness and better relationships with family and friends, said Jeong Yong-mun, the head of the center.

Jeong said he is pleased when people are able to reconcile at a family member’s funeral. But he is saddened that the connection could not happen sooner.

“We don’t have forever,” he said. “That’s why I think this experience is so important – we can apologize and reconcile sooner and live the rest of our lives happily.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

More people want a green burial, but cemetery law hasn’t caught up

by Alex Brown

Visitors to the White Eagle Memorial Preserve in southern Washington won’t find rows of headstones, manicured lawns or pathways to a loved one’s final resting place. Instead, they stroll through an oak and ponderosa forest set within more than a thousand acres of wilderness.

Twenty acres of the wilderness is set aside as a cemetery. Bodies are placed in shallow graves among the trees, often wrapped in biodegradable shrouds, surrounded with leaves and pine needle mulch, and allowed to decompose naturally, returning nutrients to the soil. Grave markers are natural stones, said Jodie Buller, the cemetery’s manager—”rocks that look like rocks.”

“People drive their loved one out themselves, in the back of a Subaru,” Buller said, summing up White Eagle’s granola ethos.

Conservation cemeteries like White Eagle, which was founded in 2008, are still few and far between—only seven have been officially recognized by the Green Burial Council, the industry’s certification body—but they’re part of a growing movement to handle the dead in eco-friendly ways.

Green burial, the catchall term for these efforts, takes many forms, from no-frills burials in conventional cemeteries to sprawling wilderness conservation operations. Cemetery operators say they’re seeing increasing interest in these less conventional end-of-life options.

“It’s been a slow, slow growth, but we are seeing the groundswell happening now,” said Brian Flowers, burial coordinator with Moles Farewell Tributes, which conducts green burials along with more conventional options on sites in Washington state.

While no state laws explicitly prevent green burial—generally defined as burials that happen in eco-friendly containers and without embalming—cemetery operators all over the country say outdated state and local laws have made it difficult for green burial to gain a foothold.

Many followers of Islam and Judaism use similar practices, burying the dead in a shroud or coffin of untreated wood without cremating or embalming. Such techniques are allowed in every jurisdiction, but new cemeteries with an explicit focus on green burial have run into obstacles.

Cemeteries were little-regulated until the late 1800s, experts say, when officials began adding rules primarily for consumer protection. The goal was to prevent scam artists or ill-prepared operators from opening cemeteries that might later be abandoned. But the regulations establishing best practices for conventional cemeteries often inhibit green-burial practices.

“The bottom-line issue in pretty much every state is the statutes don’t contemplate this kind of burial ground,” said Tanya Marsh, a professor at the Wake Forest University School of Law who has written books about laws pertaining to the dead. “It’s probably not that the legislators wanted to make things difficult; it just didn’t occur to them that everybody wasn’t going to set up a cemetery in what they conceived of as a regular cemetery.”

While no organization keeps a comprehensive database of all state and local cemetery laws, operators have no shortage of stories about the obstacles they’ve faced. Some laws, for instance, require paved roads to burial plots. Others mandate fencing around cemeteries—both antithetical to the natural settings required for conservation cemeteries.

Many states mandate that new cemeteries set up a large endowment fund for future maintenance, which green-burial advocates say is a burdensome requirement for places that are intended to be left in their natural state.

Some states require a licensed funeral director to handle transportation, and some laws mandate refrigeration or embalming once a person has been dead more than 24 hours. Green-burial advocates say families should be allowed to take care of arrangements themselves, and these laws are based on misguided fears that the dead carry diseases.

In many places, local officials may not give green cemeteries the zoning permits they need or may pass other regulations to block them. In 2008, for instance, commissioners in Georgia’s Mason-Bibb County adopted an ordinance requiring leak-proof containers for burials after neighbors complained about a proposed green-burial cemetery.

Advocates say their movement is long overdue. According to the California-based Green Burial Council, cemeteries in the United States put more than 4 million gallons of embalming fluid and 64,000 tons of steel into the ground each year, along with 1.6 million tons of concrete.

Consumers are shifting their behavior as well. More than half of the dead in the United States are cremated today, according to a report from the National Funeral Directors Association, up from an industry-estimated rate of just 4% in the 1960s.

That’s at least partially because cremation is less expensive, but some Americans also have expressed a desire to leave a smaller environmental footprint. However, the council estimates that cremation—which involves heating a furnace to close to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit for up to two hours—produces about the same emissions as driving 500 miles in a car.

Burial also is a land-use issue, as cemeteries must claim ever-increasing acres to accommodate new arrivals. Conservation cemeteries, on the other hand, are designed to preserve and expand existing wilderness areas while using the burials as a funding mechanism for the environmental work.

White Eagle, which has buried about 85 people so far and has reserved another 130 sites, charges a little more than $3,000 for a burial, which helps with continued land acquisition, invasive-species monitoring and forest management to reduce wildfire danger.

A 2019 survey from the funeral directors’ association found that nearly 52% of Americans expressed interest in green-burial options. Most cited environmental reasons, but others mentioned cost.

“Most people know what green burial is,” said Lee Webster, who heads education for the Green Burial Council. “They just don’t know how to make it happen.”

The council currently recognizes 72 cemeteries in the country that conduct green burials, ranging from “hybrid” cemeteries that allow green burials alongside conventional plots to conservation cemeteries that can span vast wilderness areas. While an increasing number of cemeteries are adding green options, operators say they face many hurdles in trying to set up new cemeteries dedicated to the practice.

Heidi Hannapel and Jeff Masten run Landmatters, a consulting firm based in North Carolina that helps those seeking to establish conservation cemeteries. The partners are attempting to set up their own such cemetery in North Carolina, but obstacles have stalled the project.

“We’d have to pave an entire road throughout the property,” Hannapel said. “That completely defeats the purpose of what we’re trying to create. We’d have to establish a large endowment that would have to be held back. There’s no room within existing North Carolina law that allows for what we’re talking about.”

Freddie Johnson, executive director of the Prairie Creek Conservation Cemetery in Florida, said the cemetery does not sell sites in advance, which exempts it from state statutes that would have required more than $250,000 upfront. However, that requirement makes it difficult for customers who can’t pre-plan their burials.

“The whole industry is set up to accommodate modern burial,” Johnson said. “You’re trying to do something simple and better for the environment, and some rules and statutes become hurdles. There needs to be another model available for cemeteries to choose based on natural and conservation burial.”

Few states are looking at changes to their burial policies. Wisconsin legislators are considering a bill to allow alkaline hydrolysis, an eco-friendly form of liquid cremation that uses a pressurized solution to rapidly decompose a body. But green-burial operators say they’ve seen little action on policy related to their cemeteries.

Aside from regulatory hurdles, operators say there’s also much work to be done in educating consumers.

“Everybody assumes you need to be embalmed or you can’t transport unembalmed bodies,” said Kimberley Campbell, who operates Ramsey Creek Preserve, a conservation cemetery in South Carolina. “The idea that you’re going to be spreading disease if you don’t embalm the body is complete codswallop.”

Buller, who manages the preserve in southern Washington, said she would like to see hospital chaplains and hospice workers present green burial as an option when they talk with families about their end-of-life choices.

Meanwhile, the so-called death care industry has begun to offer options with various “shades of green”—such as wicker caskets, urns designed to grow into trees and an organic mixture that reduces the toxicity of cremated remains, allowing for safe mixing into the soil.

In Washington, lawmakers passed a bill earlier this year allowing for human composting. The measure was based on a technology that rapidly converts human bodies into soil. State Sen. Jamie Pedersen, the Democrat who sponsored the bill, said it enjoyed broad support.

The bill passed on an 80-16 vote in the House and a 38-11 vote in the Senate. Among those opposed was the Washington State Catholic Conference, which argued that human composting disrespects the body in a manner against church teaching.

“The Catholic Church strongly recommends that the bodies of the deceased be buried in cemeteries and other sacred places,” the conference said in a news release when Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee signed the bill. “The practice of burying bodies of the deceased shows a greater esteem towards the deceased.”

Pedersen said that he would be open to looking at more changes to state law to accommodate green burial.

“If there are obstacles to responsible practices for the disposal of human remains,” he said, “it makes sense for us to clear those away and leave space for the practice to develop.”

Any movement to change cemetery law would make Washington a rare case, said Marsh, the legal expert.

Some in the green-burial movement blame that on the existing funeral industry, which they believe has outsize political influence, as well as control over many local cemetery commissions. But Jimmy Olson, spokesman for the National Funeral Directors Association, noted that many conventional cemeteries are adopting their own green options.

“With cremation rates now over 50%, I would think they would welcome this with open arms, because they would see this as an option to continue to use their cemeteries,” he said. “This is only going to help them as more and more people choose not to use a cemetery.”

Joshua Slocum, executive director of the Funeral Consumers Alliance, said it’s important for customers to know they can opt for a green burial—and save money—at many conventional cemeteries, simply by declining options that aren’t eco-friendly.

Some green-burial plots are less expensive than conventional ones, but they still cost more than cremation. However, because of the costs for embalming, caskets and vaults, green burials are often more affordable than the full cost of a conventional burial.

The typical U.S. funeral costs more than $8,000, according to the funeral directors’ association, even before the purchase of a cemetery plot. An average burial plot costs from $1,000 to $4,000, according to the life insurance company Lincoln Heritage. Green-cemetery operators interviewed for this story charge from $2,000 to $4,500 for plots.

“Everything about death is so commercialized that we have a hard time thinking about anything other than a product that can be purchased,” Slocum said. “No state requires embalming as a condition of being buried. No state law requires a coffin or casket. No state requires a concrete vault.”

Still, he acknowledged that many who choose green burial may prefer not to be put in the ground between plots with vaults, caskets and embalmed bodies. Regulations may need to change to accommodate new cemeteries that don’t fit the traditional mold.

“We need to get over this idea that everything needs to look like an MGM backlot and manicured within an inch of its life,” he said. “I’m hoping that the artificial prissiness that has dominated the American approach can go away.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

‘Pre-grieving is important – we talked, cried and laughed with Mum before she died’

Most of us think of experiencing grief after a death, not before, which means anticipatory grief is less talked about

Most of us think of grief occurring after a death. But anticipatory grief, or pre-bereavement, the painful emotions we feel before death, is experienced by many people facing the impending loss of a loved one or their own death. But as this experience is spoken about less often, some find it difficult to express the deep pain they are feeling and fail to receive the support they need.

Claudia Tanner spoke to Max Cassily, a 28-year-old area manager at Aldi, from Canterbury, Kent, about how he and his family dealt with his mother Nanda’s terminal illness at 54.

My dear mum was diagnosed with sarcoma, a cancer of the bone and soft tissue, in 2017. She’d shrugged her symptoms off as back pain.

She’d had cancer – of the breast – two years earlier and we thought we’d been through it all and it was over, she’d beaten it.

But this time around, the doctors told us straight: it was incurable. Our lovely, kind mother was going to die. They said she had three months left.

I remember just after we were told the bad news, all four of us – myself, mum, my dad Steve and my sister Ruby who is two years younger than me – all hugging and crying as we sat on a hospital bed.

They say there’s five stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Perhaps because we had dealt with my mum having cancer before and we had already felt all the anger and sadness, we were able to move more quickly to the acceptance stage. It was dad who said to us something along the lines of “We have got to do this, and accept this is happening.”

We knew we had to embrace this, talk about it, plan for it, cry about it.

I remember leaving the hospital, and the daughter of a woman with Alzheimer’s who was in the bed next to my mum hugged us and said she had loved sitting and listening to our conversations.

Open attitude about death

Last time it was all about staying positive and helping mum pull through. We knew this time, that approach wouldn’t help at all. It was a difficult decision to stop “fighting” her illness, but this was part of the process of accepting what was happening.

You may feel angry, mum was too young to go. It wasn’t fair. But you are so sharply aware of the fact there is little time to waste. Mum was going to die and we didn’t have long. We wanted to cherish the precious time we had left with her and make the most of it. Mum lived 180 miles away from me in Eastbourne, so I arranged with my employers to allow me my two days off a week to be taken together so I could spend quality time with her.

We took a really open attitude to talking about death and making practical arrangements. We announced on Facebook and other methods to everyone who knew Nand, as she was know , that she didn’t have long left and invited people to come visit our house week in, week out.

Mum had been a drama teacher who had spent half her time in Cyprus. People from all over, some she hadn’t seen for years, were grateful for the chance to say goodbye. They would apologise for breaking down, and we’d assure them it was okay. It’s only human to get upset.

We talked with mum about what funeral arrangements she wanted. She wanted to be cremated. She loved pink and was known as “The Pink Lady” due to her hair colour. She wanted a pink casket and a pink hearse. We were able to find the first but not the latter – there mustn’t be the demand for them!

She didn’t wan’t the flowers to go to waste and be cremated with her. She requested that everyone take a single stem home with them to enjoy.

Video camera to cherish memories

We had set up a video camera to record our chats with Mum. This helped with the practical side of remembering her wishes. It also allowed us to cherish the memories she shared.

There were plenty of tears, sad ones and happy ones. It was difficult watching her break down and grieve her own death.

But there were positives. It was a time to learn more about my mum’s past. I knew dad didn’t have a great memory so I wanted to take the chance to ask her all about her childhood and upbringing.

Mum was 26 when she met dad and he was just 18. It was unusual in those days, and she was the one who dealt with the more adult things – she was the breadwinner who got them their first house.

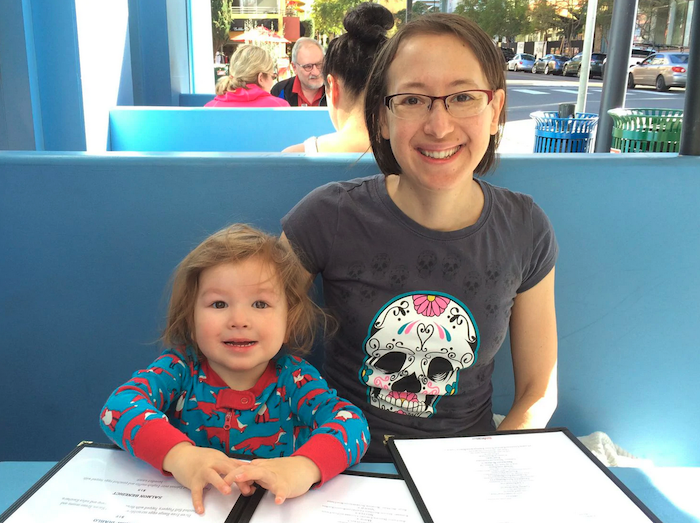

At one point, she looked deep in thought and she turned to me and my sister and she said, “You are all okay, you’re all happy aren’t you?” She knew Ruby had her boyfriend and child. She told me I was going to marry my girlfriend Nina. To be honest, I hadn’t even thought of marriage at that point. But mum, you were right, Nina and I tied the knot earlier this year.

Saying goodbye

‘Talk about everything. It won’t change the fact that someone you love is about to die; but I promise you, it will certainly help’

We had lots of trips out, coffees and lunches, until mum got too tired and wanted to stay indoors. The last month was hard watching her struggle for breath.

On 27 February 2018, mum was rushed to A&E. She passed away while I was travelling in a desperate rush to get there on time. I remember balling my eyes out while driving, and not wanting to stop as I wanted to get to the rest of my family as quickly as possible.

I’d never seen a dead body before. I found it really helped to see Mum’s. She looked so peaceful and not in any pain, in stark contrast to the last few months.

Over 250 people attended her funeral. We live streamed in on Facebook and thousands watched it from 21 different countries.

I found it so comforting to watch back the videos of Mum in the months after her death. I got to see her laughing at jokes, crying at the situation, chatting about her first house that she bought 30 odd years ago. Just seeing how she was in her normal, every day life was lovely.

I started a blog about grieving to help other people deal with loss, which can be found here. It can be so easy to go into denial and not face difficult emotions when someone you love is dying. If I can help one person going through the same, that would be great.

Talk about everything. It won’t change the fact that someone you love is about to die, but I promise you, it will certainly help. I had felt I had to be “the strong one” to help everyone else out. So when someone asked how I was, I’d say “Yep, I’m fine”, when really I wasn’t. So I called a men’s mental health line. It helped to speak to someone I didn’t know.

Pre-grieving is an absolute emotional rollercoaster. At times you’re going to be frustrated, sad, angry and even happy, and that’s fine.

Max’s tips when facing a loved one’s death

Max’s blog outlines several pieces of advice:

- Talk – if you don’t feel comfortable sharing with someone close speak to a professional. It’s okay not to be okay.

- Capture you loved one on video – not only does it encourage you to talk through things, it also means you have memories on record and it can be a comfort to watch your loved one when they are gone.

- Look after yourself – you cannot expect to look after and support your loved one if you don’t look after yourself.

- Encourage people to say their goodbyes – it’s a chance to reminisce about old times and just generally have a laugh and forget about death.

- Plan the funeral with your loved one – you’ll find comfort in knowing you’re following their wishes.

- Embrace normality- try and do normal things as much as possible. Go for coffees, shopping, a meal, have friends over, watch TV, get a takeaway, and so on. A loved one with cancer is still a loved one, so, when possible, treat them the same and do the stuff you always used to do together.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Start the conversation:

What parents should know about teen suicide

If you see signs of distress in your teen, here is what you need to know before starting a conversation with your teen.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people ages 10-24 in the United States, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Talking about suicide can be just as difficult as detecting the warning signs.

The Tennessee Suicide Prevention Network has a resource guide detailing what you should watch out for and how to talk about it with your child.

Warning signs:

- Talking about suicide, death, and/or no reason to live

- Preoccupation with death and dying

- Withdrawal from friends and/or social activities

- Experience of a recent severe loss (especially a relationship) or the threat of a significant loss

- Experience or fear of a situation of humiliation or failure

- Drastic changes in behavior

- Loss of interest in hobbies, work, school, etc.

- Preparation for death by making out a will (unexpectedly) and final arrangements

- Giving away prized possessions

- Previous history of suicide attempts, as well as violence and/or hostility

- Unnecessary risks; reckless and/or impulsive behavior

- Loss of interest in personal appearance

- Increased use of alcohol and/or drugs

- General hopelessness

- Recent experience of humiliation or failure

- Unwillingness to connect with potential helpers

Three Farragut mothers who lost children to suicide over the course of three years pointed to sleep deprivation, school pressure and social media as major contributors.

What you should do:

- Be aware. Learn the warning signs.

- Get involved. Become available. Show interest and support.

- Ask if they are thinking about suicide.

- Be direct. Talk openly and freely about suicide.

- Be willing to listen. Allow for expressions of feelings and accept those feelings.

- Be non-judgmental. Don’t debate whether suicide is right or wrong, or feelings are good or bad. Don’t lecture the value of life.

- Don’t dare him/her to do it.

- Don’t give advice by making decisions for someone else to tell them to behave differently.

- Don’t ask “why.” This encourages defensiveness.

- Offer empathy, not sympathy.

- Don’t act shocked. This creates distance.

- Don’t be sworn to secrecy. Seek support.

- Offer hope that alternatives are available. Do not offer shallow reassurance; it only proves you don’t understand.

- Take action. Remove means. Get help from individuals or agencies specializing in crisis intervention and suicide prevention.

“If you have concerns, it’s OK to just ask someone, ‘Are you considering suicide?’ They’re not suddenly going to say, ‘Hey, that’s a great idea.’ If they’re not considering it, they’re just going to say no, but if they are considering it, you might open that doorway [to talk about it],” said Candace Bannister, one of the mothers who lost her son to suicide. “Maybe Will would’ve responded had I known to ask that question. It didn’t know what was on his mind.”

Suicide Prevention Resources

If you or someone you know needs help, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Crisis Text Line: Text TN to 741741 if you’re struggling with thoughts of suicide.

Additionally, the peer recovery call center available in East Tennessee, where those who answer the hotline have first-hand experience in the area.

The center can be reached at 1-865-584-9125 between 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.

Lifeline Crisis Chat: Chat online with a specialist who can provide emotional support, crisis intervention, and suicide prevention services.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Hereafter

What does it mean to create new life when one parent is dying?

Ben Boyer can still picture the expression on his wife’s face that night six years ago, as they talked over dinner at their favorite Italian restaurant in London. It had been four years since Xenia Trejo had been diagnosed, at the age of 33, with a malignant brain tumor that doctors said would eventually end her life. But as she sat across the table from Ben that evening, Xenia radiated joy. She felt strong, and after numerous rounds of treatment, her doctors had just told them that Xenia’s tumor was stable enough to do something she had long dreamed of: pursue a pregnancy. Now Xenia was asking Ben, What do you think? Should we try?

They had always planned to be parents, and the possibility had hovered even since Xenia’s diagnosis, but now it finally felt within reach. “Let’s do it,” Ben told her. By the time they left the restaurant and walked home together, they knew they would try to start a family. In that hopeful moment, the reality of their circumstances felt far away.

There are countless parents who don’t live to see their children grow up, but most of those tales involve unforeseen tragedy. The story of Ben and Xenia was different. When they learned of her illness, the future Xenia and Ben had long envisioned for themselves came undone, and an urgent reckoning followed. What would they fight to keep of the life they once imagined? In the face of a certain ending, they chose to create a beginning.

The number of people who confront this exact extraordinary convergence of birth and death is small enough that no one knows precisely how many are out there. “It is probably a very small number, though not an insignificant number,” says David Ryley, a fertility specialist at Boston IVF and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School. “I think you won’t find that data, because it hasn’t been collected.”

Yet there are outliers facing terminal illness who have forged ahead with plans to have children. Among them are a few who have risen to cultural prominence after sharing their stories: Paul Kalanithi, the neurosurgeon and author of the best-selling, posthumously published memoir “When Breath Becomes Air,” dedicated his book to his infant daughter, who was conceived after Kalanithi was diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer. Nora McInerny, host of the popular grief-focused podcast “Terrible, Thanks for Asking,” has widely shared her experience of having her son, Ralph, with her late husband, Aaron Purmort, who learned he had brain cancer before they were married. Ady Barkan — a prominent liberal activist who was diagnosed three years ago with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, a neurodegenerative disease for which there is no cure — recently welcomed an infant daughter, his second child with his wife, Rachael King.

These are distinctly modern stories. For couples who confronted grim diagnoses before the turn of the millennium, the option to preserve their fertility was much harder to find and less likely to succeed. But the ability to freeze and test embryos improved dramatically in the early 2000s, bringing with it complex existential questions. What would it mean to have a baby in these circumstances for the parent who would die? For the parent who would live? For their child?

Xenia, Ben recalls, was not inclined to dwell on questions she felt she couldn’t answer. Her “entire M.O. was to live one day at a time, and she did not want to entertain larger metaphysical and moral debates about what this meant,” he says. He, however, was initially more hesitant. “I was a lot more nervous about what that meant for us, for her, and she was the one saying, ‘We should do it,’ ” Ben says. “For her it was, ‘I have to do this.’ I think she was put on this Earth to do it. She loved kids so much, it was not even a question. For me, I wanted to do whatever she wanted to do, but I also think I played the devil’s advocate more than once — ‘Here’s one possible reality, here’s another possible reality.’ But Xenia’s entire thing was, ‘If I let myself get mired in all the theoretical possibilities, I won’t be able to live a life at all.’ ”

And so they didn’t spend much time trying to decipher an unknowable future. Once the doctors said there was no reason to expect that a pregnancy would threaten her health, Ben says, “it was a given that we were going to try to do it.” In February 2014, Xenia gave birth to their daughter, Ella. Ben still recalls the euphoria of watching the nurse place their newborn on Xenia’s chest. He still can’t quite believe the song that played on the operating room radio, the refrain resounding in that moment: God only knows what I’d be without you.

Ben had first met Xenia in 2003, when they both worked for the BBC’s Los Angeles office. He was drawn immediately to her warmth, humor and adventurous spirit, and they fell in love quickly. Three years into their relationship, Ben transferred his job to London, and Xenia followed soon after. They were in their early 30s then, overjoyed to be living together for the first time in their tiny studio apartment. Ben remembers one particular afternoon in the winter of 2007, when they walked home together through falling snow, and he felt a deep sense of belonging: They would be married, have a family together, grow old together.

But in 2009, Xenia was struck with a wave of debilitating headaches. A seizure soon followed, which led to the discovery of the tumor in the frontal lobe of her brain. The doctor who delivered the news was shockingly blunt. “He immediately said, ‘So, you know, I assume you understand that you might die within a year,’ ” Ben recalls. “I remember thinking: This can’t be right.” As it turned out, it wasn’t: The couple quickly sought opinions from other doctors, who explained that while the prognosis was ultimately terminal, there was no reason to predict such a grim timeline.

They had been together for six years by then, and though they were not yet engaged to be married, their commitment to one another was absolute. Before Xenia started chemotherapy, the couple froze several embryos.

From the beginning, there were doctors who offered statistics, percentages, who told them how likely she was to still be alive in three years or five. There were also doctors who voiced a more universal truth: We can’t know with certainty what will happen, or when. Some patients with Xenia’s cancer died soon after diagnosis; others lived two decades or more. “Some people think of these things mathematically,” Ben says. “Some people think of them cosmically.” Xenia had always been, would always be, among the latter, he says. She would not be consumed by the inevitability of loss. “She refused to live like this was a death sentence,” he recalls, “even though it was explicitly a death sentence.”

Her treatments halted the progression of her illness, allowing them to resume their lives, and in 2011, they planned their wedding. Ben remembers the question Xenia once asked him, a few months before the ceremony: Are you sure you still want to do this?

He was. They were married that September on a historic ferryboat moored in San Diego Bay, surrounded by their loved ones. And two years later, over that dinner in London, they decided to move forward with building a family. They wound up not needing the embryos they’d frozen; Xenia became pregnant soon after they started trying to conceive.

From the moment Ella arrived, Xenia embraced motherhood, Ben says; she relished every minute of her 14-month maternity leave. She had always been a spontaneous and outgoing person, so it didn’t surprise Ben when she hopped on a train to Scotland with their baby to join Ben at a comedy festival, or showed up to bustling happy hours at their favorite pubs with Ella in tow. “We had an awareness that there was a finite number of experiences we were going to share together, and we knew we had to grab on to those moments,” Ben says. “We wanted to get out and experience whatever we could while we still could.”

Late in 2015, Xenia suddenly suffered an onslaught of seizures, and doctors confirmed that her cancer had begun to advance. Within months, the family moved back from the United Kingdom to San Diego, Xenia’s hometown. Her health continued to decline, and in the fall of 2017, Ben, Xenia and Ella moved in with Xenia’s parents, settling in the little house in San Ysidro where she had grown up. In those days, Xenia sometimes spoke to Ben of her sorrow for what she knew was coming. “She would say things like, ‘I’m so sorry you got stuck with this,’ ” he remembers. “She would ask if I regretted anything. And I would say, ‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ I would tell her, ‘This was the best thing of my whole life, that I met you, that I got to have this time with you.’ ”

Toward the end, a therapist suggested that Xenia might consider writing a letter to Ella, something she could read years after her mother was gone. Ben and Xenia were both aware of viral stories about dying parents who left behind written or recorded messages, birthday cards for their children to remember them by. But Xenia didn’t know who Ella would be at 16 or 20; she did not want her daughter to feel bound or burdened by parting words from a mother who had long been absent, Ben says. Xenia wanted Ella to be free.

Xenia’s decline was swift, her illness eroding her cognitive functioning, robbing her of language and distorting her personality. Through the darkest of those days, Ben says, Ella remained the one immovable tether to Xenia’s sense of self. Sometimes she would try to talk to her daughter, and couldn’t. “This,” Xenia would say to Ella, the only word she could summon; “this, this,” she would say with mounting urgency, and Ella would grow unsettled by the sudden intensity. But more often, there was an obvious contentment when the two were together. “Ella would walk in the room, and Xenia would immediately smile and become animated,” Ben says. “She was always so happy when Ella was around.”

On her last morning, Xenia awoke unable to speak. Ben and Ella lay with her as the house filled with family. She died that afternoon, a bright Sunday in May: Mother’s Day.

Buried in the digital archives of MetaFilter, an online message board that predated Reddit, is a question posed by an anonymous husband in 2010; he explained that his wife had been treated for an aggressive brain tumor, but they desperately wanted to be parents, and he wondered whether having a child was a wise or ethical choice. Hundreds of replies unspooled below his post, passionately voicing every imaginable viewpoint:

“You’re in for a world of trouble if you do it. But it may be the thing that you need to do.”

“Having lost a mother to cancer … I do think it is selfish to knowingly bring a child into the world knowing full well that the child will have to watch one of its parents die, and then grow up without them.”

“As someone whose father died when I was eight, I think you should do it.”

The medical community has grappled with this question as well. In 2005, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine convened a group of reproductive biologists, obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians and medical ethicists to weigh in on whether cancer survivors should be allowed the opportunity to reproduce, given the potential of a decreased life span. “It’s important to note there, the potential of a decreased life span,” says David Ryley, the Boston-based fertility doctor, who specializes in treating patients who have been given a cancer diagnosis. “Nothing in medicine is zero percent. Nothing in medicine is a hundred percent.”

The expert panel’s formal conclusion was clear, Ryley says, reciting it aloud: “The child in question will have a meaningful life even if he or she suffers the misfortune of the early death of one parent. While the impact of early loss of a parent on a child is substantial, many children experience stress and sorrow from economic, social and physical circumstances of their lives.”

“I could get hit by a bus today. How do I judge a couple who wants a child but may suffer misfortune?” Ryley continues. “Reproductive freedom is well established in this country, and this is a personal choice. We have patients seek counseling to help them get through that minefield, to not let them feel judged, to know that the choices they make are in the best interest of their life, their family, their relationship, and to understand that what is important is how they feel.”

Those sentiments are echoed by Merle Bombardieri, a therapist and author in Massachusetts who specializes in parenthood decision-making and often urges her clients to focus on inward reflection. For more than 30 years, she has counseled couples and individuals who struggle to decide whether to have a child, and she has worked with numerous people who faced grave health concerns.

This subset of her practice requires a somewhat different approach, she says, because they’ve already leaped beyond what she views as a foundational objective of her work, which is to ensure that her clients have considered their decision within the context of their own mortality. “Do you know that you will die one day?” Bombardieri says. “On one hand, that’s a ridiculous question, because everybody knows they’re going to die one day. But do you really know? Have you thought about what that means? Are you comfortable with your choice, knowing that you won’t be here forever? If you are, then you can feel more certain that it is the right choice.” For clients facing dire diagnoses, “this awareness has already come for them,” she says, which leaves other, more logistical factors to sort through: What is the prognosis? What sort of support system — community, family, friends — is available to offer help? What is the family’s financial situation?

Still, Bombardieri says, the most powerful motivations come from a more visceral place, where a person must reconcile hope with reality, and decide what they feel is still possible. “There are people who have always believed that they would have a child someday,” she says. “And, of course, there is the idea that — even if you die — you have left a child behind in the world. And that, too, is a kind of survival.”

Ella’s fingers grip her father’s, tugging him along as they walk a winding path through the San Diego Zoo, surrounded by life in all its strangest and most extraordinary forms: cheetahs and rhinos, gorillas and parrots. Ben and Ella are talking about how Xenia loved this zoo, and Ella, now 5, suddenly realizes that she isn’t sure what her mother’s favorite animal was. “I think I don’t know,” she says, her brow furrowed behind her violet-rimmed glasses, but she offers up her own favorite instead: “Flamingo!” she shouts.

They used to come here often as a family of three. These days, Ella usually visits with just her dad, or sometimes with friends she’s made at a therapy group for children who have lost a parent. On this idyllic October afternoon, the children’s area of the zoo is closed for renovation; when it reopens, it will include a brick engraved with Xenia’s name.

Ben took many photos of Xenia in this place, some of which are tucked into albums that Ella loves to look through. Later in the evening, after Ben and Ella return home from their outing, Ella sits cross-legged on the living room couch, studying an image of her mother outside the flamingo enclosure at the zoo. Xenia’s pose imitates the birds, one leg bent at the knee. “She has a pink shirt!” Ella says.

She pulls another album into her lap. “This is my favorite picture,” she says, pointing to a photo of herself at 5 months old, lying in bed beside her mother. Xenia is sleeping, a sheet drawn to her chin, but Ella is wide-awake, flashing a mischievous smile at the camera.

This particular album, capturing their first moments as a family, was Ben and Ella’s last gift to Xenia. Ella turns the pages past pictures of her birth, her ecstatic parents cradling their swaddled newborn. She resembles both her mother and father, but in photos with Xenia, the likeness is unmistakable: Ella has Xenia’s light brown hair and bespectacled dark eyes, the same wide grin and expressive eyebrows.

Their similarities run deeper, surfacing in new ways in the months since Ella started kindergarten at a Spanish immersion school, where she is learning to speak fluently in the native language of Xenia’s Mexican American family. The child’s exuberant sense of humor, her kindness, her boundless enthusiasm for Halloween, her deep sensitivity to music — to Ben, all of this feels like glimmers of Xenia.

Ella is growing up in the city where her mother was raised, where Ben now feels he has to stay. “Everyone is here,” he says. Everyone includes his parents — who own the condo he shares with Ella, and are his neighbors down the hall — and his sister’s family, and Xenia’s family, too. He can’t imagine taking his daughter away from here, even though it is a difficult place to find work in television production. When he and Xenia decided to have a child, their closeness to their families was at the forefront of their minds, he says. “We knew: This child will be surrounded by love.”

Outside Ben and Ella’s living room windows, the sun drops over San Diego Bay. When Ella reaches the end of the album, Ben scrolls through older photographs on his laptop. There is a portrait of Ben and Xenia’s wedding party, pictures of Ella trick-or-treating in a tiny bat costume, splashing in a backyard baby pool, sitting on her mother’s lap at Legoland.

Ben pauses on a photograph of Xenia framed by an array of vivid bouquets. “This was right after she was diagnosed,” he says. “Those are flowers that people sent.”

“What is ‘diagnosed’?” Ella asks.

“After we found out Mommy was sick, people sent flowers to say they were sorry about that,” Ben explains.

Ella nods and falls quiet. Then she smiles. “I wish I was a flower girl at your wedding,” she says.

There are questions that hover over the years ahead: What might Ella’s life be like when she is older — when she understands more about how she came into this world and what happened to her mother? How might she relate to Xenia’s memory? Every experience of grief is unique, its reverberations often impossible to predict. But the Kim family, who were patients of David Ryley 14 years ago, offers one glimpse of how a profound decision made in staggering circumstances can look more than a decade later.

Stacey Nichols met John Kim at a mutual friend’s party in Boston in spring 2003. He was an outgoing and deeply empathetic man with a “boundless wellspring of patience,” Stacey says — qualities that served him well as a school counselor who worked with kids with special needs. He moved in with Stacey three months after their first date; they got engaged that Thanksgiving.

Before their wedding in August 2004, John began suffering from sporadic gastrointestinal issues, and his doctor ordered diagnostic tests. The results were concerning, and further scans showed lesions on his liver. Three weeks after they were married, an oncologist told them that John had Stage 4 pancreatic cancer. “It felt like a complete emptying of my soul,” Stacey says of that moment. “All I could do was just be there, trying to make myself understand: ‘I’m here. I’m actually me. I’m not going to wake up from this.’ ”

Even as they were reeling, John wanted to know how his chemotherapy might affect their chances of having a child. The doctors didn’t have an answer. “There hadn’t been research on how this particular regimen affected fertility,” Stacey says. “The gist of what his oncologist said was, you know, patients who do these treatments for pancreatic cancer aren’t having kids; they die.” But John had always wanted to be a father, and they had to decide quickly whether they wanted to preserve that possibility. They postponed John’s treatment for one week so he could visit a sperm bank.

Eight months later, with John responding well to chemotherapy, the couple set out on a walk together and talked about starting their family. For the first time since their wedding day, Stacey felt a rush of pure joy and anticipation. “We didn’t know what was going to happen, but it felt almost defiant, somehow,” she says. “We felt like, this is a long-term plan. It is a decision only the two of us can make.”

They found out Stacey was pregnant with twins, a boy and a girl, in October 2005. When the babies were born the following June, John wrote their full names in the pages of a journal — Madeleine Ji Yun Kim and Riley Chen Woong Kim arrive!!! — alongside delicate drawings of fireworks. The exhilarating haze that followed lasted six months, Stacey says, before John’s cancer resumed its assault. The twins thrived as their father began to fade.

The exact chronology of John’s last days (what he ate, what time he took his medications — details Stacey could once recite with precision) are lost to her now. She remembers clearly, though, how she left the door to their bedroom open as John rested there in his final hours, so the sounds of his family living their day — the babies playing and giggling, splashing in their bath — could still reach him.

After John died in April 2007, Stacey made a point to speak of him often; she wanted her children to know that the subject of their father should never feel taboo. “They do love it if I bring him up; they love when I tell stories about him,” Stacey says. “I make sure to continue to remind them that it’s okay to grieve his loss for their whole lives, in whatever way they need to.”

Ten years ago, Stacey and her children moved to Portland, Ore., to be closer to her parents. Stacey is now 47, the director of marketing and communications at Lewis & Clark College, her alma mater; Maddie and Riley are 13, on the cusp of their high school years. Lately, Stacey says, they have started asking more questions about John, about what he was like, the similarities they share with him. As they’ve grown, they’ve become more aware of their biracial identity, their connection to John’s Korean heritage. They have lived all but 10 months of their lives without their father, and so their grief is not the loss of a known reality, but the absence of a possibility: Would John, who used to read Julia Child’s recipes aloud to Maddie, have celebrated his daughter’s love of cooking? What would it have been like for Riley to share his passion for video games with his dad, who was also an avid gamer? “I like to play chess, and I run cross country,” Riley says. “Those are things I think he would have been into.” He smiles. “You know, he was into nerd boy things, and I’m like that, too.”

Maddie thinks it must have been difficult for her dad to decide to become a parent, knowing he would miss out on so much of their lives. “But I’m so glad he did it. I think Mom would have been lonely. I mean, David is great,” she says, referring to Stacey’s boyfriend of several months, with whom the twins share an easy rapport. “But I still think she would have been lonely without us. And I feel like Dad’s entire side of the family would have missed him a lot more. They tell us all the time, ‘Oh, you really remind us of your dad, and that’s a really good thing.’ ”

The twins are especially close, often ending their days by taking walks together around the block to decompress and tell each other what’s on their minds. (“Some people say their brothers are annoying, but I really love my brother,” Maddie says.) Even without their father, Maddie says their family has always felt like enough. She wishes her dad could somehow know this. “I would like him to have that reassurance,” she says. “To be able to know that everything is okay, and that we are happy.”

John is the beginning of their story, and his family has since lived their way into a chapter he would not recognize, here in their lovely house on a tree-lined street in North Portland. His ashes rest on a shelf in the living room, a colorful gathering space strewn with books and musical instruments, often filled with the voices of visiting friends and family.

Even 12 years on, in this place he never knew, John’s absence sometimes echoes with startling immediacy: Stacey realizes with a jolt that she forgot to put on her wedding ring, and it takes a moment to remember that she hasn’t worn it in years; Maddie laughs, and her expression is suddenly her father’s; Riley holds Stacey’s hand and instinctively traces his fingertips across her cuticles, exactly the way John once did. They are here, and John is where John is, and there are moments when it still feels like the door between is open.

Ben has never forgotten something his mother once told him, soon before Xenia died: that for Ella, losing her mom would be the defining fact of her life. He thinks about this, in moments when he feels his aloneness most acutely — at play dates with other families, where he is often the only single dad, or when Ella asks for a French braid and he realizes he doesn’t know how to style her hair that way. “We just have to do the best we can for her,” he says.

When Ella decides to be a jellyfish for Halloween, Ben strings white lights from a clear umbrella and transforms his giddy kindergartner into a glowing sea creature. The two sing together, loudly and often, especially in the car. If there is somewhere Ella wants to go, something she wants to see, he takes her. This is Ben, but it is also Xenia, he says. Her way of being has become his.

And so, he feels, there is a sense of Xenia that is still palpable to Ella, even as her own recollections begin to fade. “Xenia would often say, ‘Will Ella remember me, or won’t she remember me? And which is better?’ ” Ben says. “And sometimes Ella will turn to me now and look worried, and she’ll say something like, ‘I think I don’t remember Mommy.’ ”

Ben does all he can to preserve the connection between Ella and her mother. On the first night that Ben and Ella lived alone together, the day they moved into their condo overlooking the bay, he tucked his daughter into bed in a new room and began a new ritual: Before Ella went to sleep, they talked for a little while about Xenia. At first, it was almost ceremonial; in the year that has since passed, it has become less of a nightly practice and more of an ongoing conversation, a constant referencing of things that Xenia once said or did or loved. Once or twice a week, Ella asks Ben to retrieve an old video camera loaded with dozens of hours of family footage, so they can watch it together.

Tonight, Ben is the one to suggest this, after Ella finishes her bath and changes into her pink nightgown. “Do you want to watch a couple of movies?” he asks, and Ella immediately shouts “Yes!” and dashes to her bedroom. Ben lies down on her twin bed and turns the video camera on, pointing the built-in projector toward the ceiling. “Hey, Ella, this is your first birthday party,” he says, and she grins and climbs in the bed beside him.

Ella will not remember her first birthday party. But someday she might remember watching the video of her first birthday party, and listening to her father tell her what the celebration was like. She might remember the way her mother looks in the film from that day, her slender frame draped in a striped top as she kneels and fills a large giraffe piñata with fistfuls of candy.

“Hi, Mommy,” Ella says, wiggling so her head rests on her father’s stomach. She watches as her family gathers around a picnic table where she and her parents sit before a cake, and Xenia gently rubs her baby’s back as everyone starts to sing “Happy Birthday.”

The scene unfolds, and the minutes tick past Ella’s bedtime. “Just one more, okay?” Ben says, and fast-forwards to a video taken when Ella was 3, at her first swimming lesson. When Xenia appears beside the pool, the progression of her illness is painfully evident — her hair unevenly shorn, her cheeks swollen from steroids.

“She looks very, very …” Ella trails off. She seems unsettled and climbs off the bed, crawling on the floor.

“Very what?” Ben asks her.

“Very, very …” but Ella can’t or won’t summon the next word.

In the film, Ben is talking to Xenia: “Impressive, right?” he says of their daughter’s enthusiasm in the pool, and Xenia nods and smiles.

In the bedroom, Ben is talking to Ella: “Mommy is gonna say something now,” he says. “Are you watching?”

“I’m watching,” Ella says as the camera closes in on Xenia’s face.

“We are very proud,” Xenia says, enunciating slowly.

They are together like this for a little while: Ella on the floor, gazing upward. Her father in the bed. Her mother in flickering beams of light. Then Ben says gently, “Okay, baby, it’s time for bed,” and turns off the projector. The past dissolves into shadows as Ella crawls back into the blankets, and the two of them lie there, side by side.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!