Green burials go beyond not polluting or wasting. It’s about people needing and caring for land, conducting life-affirming activities there—including death.

In March, Stiles Najac buried her partner, Souleymane Ouattara, at the Rhinebeck natural cemetary and looked forward to returning with their baby son, Zana, to picnic in the woods near his dad.

By Lynn Freehill-MayePhillip Pantuso

Initially, the cemetery in Rhinebeck, New York, appears conventional: businesslike granite squares placed in rows, flags and silk flowers sticking up here and there, grass mowed tight all around.

In one corner, however, a walking path roped off from vehicles invites visitors to stroll into the woods. The area looks wild, but it turns out to be part of the cemetery. A hardwood sign marks it the “Natural Burial Ground.” Cherry, beech, and locust trees stretch tall. Ferns cover the ground. The sweetness of phlox, a purple wildflower, wafts in the air. The lawn portion suddenly looks as contrived as a golf course.

“It’s stark, isn’t it?” Suzanne Kelly, the cemetery’s administrator, says of the contrast. On a spring day, she’s taking us on a tour of the natural section she helped establish in 2014. We step in and she starts describing the deer, wild turkeys, and songbirds that pass through (and also warns us about a poison ivy patch). About 100 yards in, we start to see mounds and a few small fieldstones, some engraved with simple words like “Dear Nature, Thank You, Evelyn.” These 10 acres have been permanently set aside for bodies to be buried without the chemical embalming, nonbiodegradable caskets, or concrete vaults that often accompany the modern American way of death.

Kelly is a thoughtful Gen X academic-turned-garlic-farmer-turned-green-burial-activist-and-expert. She remembers first feeling disconnected from standard funerals when her father died in 2000. She stared at the vinyl carpet covering his deep concrete vault and wondered what all the trappings of her dad’s Catholic service were for.

“The idea of ‘dust to dust’ seemed to be missing,” Kelly remembers. “Even though we were standing at the grave saying those words, we were not living those words.”

After moving back to the Hudson Valley in 2002, Kelly joined Rhinebeck’s cemetery advisory committee. She hoped to create options for people who wanted highly personal burials that connected to the earth. Since then, Kelly has positioned the Rhinebeck natural burial ground at the forefront of a growing international movement to reclaim death by bringing back burial traditions that are more environmentally friendly, more personalized, and more connected to place.

In 2015, Kelly wrote Greening Death, the definitive book on the grassroots efforts behind the movement. “The impetus has been to make death more environmentally minded, less resource-intensive, and less polluting,” she says. “And to tie us back to the land.”

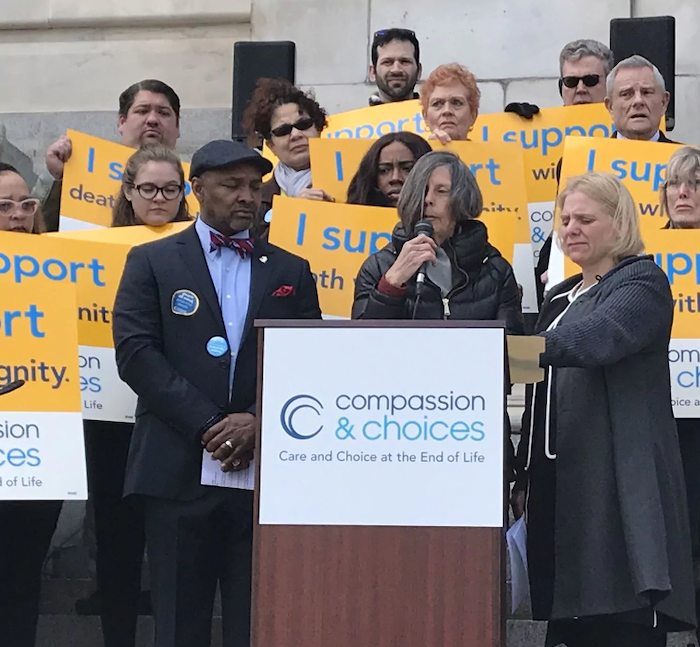

While Stiles Najac buried her partner in March, she found that the Rhinebeck ground gave her an unexpected peace. Najac was nine months pregnant with their son when her partner, Souleymane Ouattara, died by suicide last fall. Six months of bureaucratic complications followed before Najac could lay him to rest. (A medical examiner stored Ouattara’s body in a cooler, a common preservation method before natural burials.) Ouattara was an Ivory Coast native, and his Muslim family wanted Islamic “dust to dust” burial traditions, which typically eschew vaults.

So on a crisp day, Ouattara’s friends and family traversed the burial ground’s muddy lane to a chosen spot in the sun. They lowered his body into the ground using straps.

“It added another level of connection,” Najac says. “People actually returned him to the earth.”

As sunlight flickered through the branches, each mourner had a chance to speak. Ouattara’s uncle had plainly felt the stigma of a family suicide. As the service went on, Najac watched his demeanor change. His nephew was still beloved.

Afterward, though lunch was waiting, everybody lingered. “We were nestled in the trees, which create warmth on even the coldest day,” Najac remembers. “I had that feeling of comfort and acceptance. This was nature’s home.” She plans to bring their exuberant baby son, Zana, to picnic in the woods with friends in the warmer months near his dad.

Since the Civil War, American death rituals have become increasingly elaborate, complete with artificial embalming, concrete vaults, and satin-lined metal caskets. But in 1963, writer Jessica Mitford’s witty exposé of the funeral industry, The American Way of Death, sold every copy the day it was published. (Spoiler: Plenty of material is wasted along the way, but lavishly buried bodies still decay, perhaps even more spectacularly than their pine-boxed counterparts.) The book changed the way Americans thought about funerals and contributed to the growth of cremation rates, from 2% then to more than 50% today.

Still, cremation has limitations in both cost and impact. In 2017, the median cost of an American funeral with viewing and vault was $8,755, according to the National Funeral Directors Association. The median cost of a comparable cremation wasn’t dramatically less, at $6,260.

In the age of climate change, environmental concerns have also prompted more people to cremate. For example, a conventional burial contributes to the production of about 230 pounds of CO2 equivalent, according to Sam Bar, quality assurance and manufacturing engineer at Green Burial Council, a California-based nonprofit that advocates for “environmentally sustainable, natural death care.” But burning isn’t as eco-friendly as many assume. Cremation relies on fossil fuels, produces about 150 pounds of CO2 per body, and releases mercury and other byproducts into the air. Burning one body is equivalent to driving 600 miles. And scattering “cremains” isn’t good for soil.

Then a couple decades ago, activists on both sides of the Atlantic came up with similar alternatives to the $20 billion funeral industry: What if we returned to burial practices that allowed bodies to decompose naturally? And what if lands could be preserved in the process? The author and social innovator Nicholas Albery helped establish “woodland burials” in the United Kingdom in 1994. The first similar but independently generated concept in the United States was Ramsey Creek Preserve, established in South Carolina in 1998. Billy and Kimberley Campbell are proud that it is now a dedicated Conservation Burial Ground, with a permanent land trust agreement. “Instead of wasting land, you’re actually protecting ecologically important land,” Billy says.

Whether next to a regular cemetery or on conserved land, there are now around 218 natural burial grounds in the U.S. , up from around 100 just five years ago. The Green Burial Council certifies about one-third of them. (New Hampshire Funeral Resources, Education & Advocacy keeps a longer list that includes grounds not certified by the Green Burial Council, while other burial sites remain unreported.)

The Green Burial Council holds dual nonprofit status: a 501(c)(6) that certifies grounds and a 501(c)(3) that conducts education and outreach. The organization formed in response to the growing green burial movement and has since become the standard bearer of, and leading authority in, the U.S. movement. That’s no mean feat, given the divisions of purpose that have fragmented the nascent industry in the past. Lee Webster, director of the Green Burial Council’s education and outreach arm, says parts of the early movement were “very elitist,” and there is still a lot of confusion around terminology and standards.

The Green Burial Council currently has three certification standards for green-burial grounds. Certified “hybrid cemeteries” are modern cemeteries that reserve space for burials without embalming or concrete vaults (each year, burials in the U.S. use more than 827,000 gallons of dangerous chemicals and 1.6 million tons of concrete, materials that can be toxic to produce and damaging to the environment). Certified “natural cemeteries” prohibit the use of vaults and toxic chemical embalming. And certified “conservation burial grounds” meet the other requirements of hybrid and natural cemeteries plus establish a land trust that holds a conservation easement, deed restriction, or other legally binding preservation of the land.

Webster spent three years on the Green Burial Council board through 2017 and returned earlier this year to help steer education and outreach. “Because of the myth people have been sold about vaults and caskets, we have to reeducate people on the safety of bodies being buried in the ground without all the furniture,” she says.

The Council updated its standards this spring to better align them with land trust and land management conservation practices. Establishing a land trust for a burial ground lends legitimacy to what’s still a niche movement, in addition to preserving the land and creating a potential revenue stream—crucial at a time when cemetery funding is short (in large part because increasing U.S. cremation rates have cut burial-plot revenues).

As private and municipal-run burial grounds fill up, they can’t keep adding bodies, which means they have to dip into endowments to fund operations, Webster says. It’s not uncommon for a private cemetery to be abandoned when it runs out of money, at which point a nearby municipality often takes over, stretching funds even thinner.

To advocates like Webster, land conversation is the future of green burial. “The way it’s been approached has been to see it from a cemeterian’s point of view rather than a conservation point of view,” she says. “We’re going back now to encourage more land trusts to participate in this and understand how burial can be a conservation strategy.”

Others are going even further. In May, Washington became the first state to legalize body composting as an alternative to cremation or casket burial, a process pioneered by the Seattle-based company Recompose. Other companies offer still more unusual methods of handling human remains: You can have your body mummified, dissolved in water and lye, buried in a pod and planted with a tree, “promessed” (frozen, vibrated into dust, dehydrated, and reintegrated into soil), or put into the ground with a burial suit embroidered with mushroom-spore thread.

Webster believes that body composting and other methods of reintegrating human remains into the environment are “the answer” for urban settings, where burial space is increasingly scarce. So why keep advocating for natural burial grounds like the one in Rhinebeck? It’s the potential they hold for land conservation that’s exciting, she says, and remembrance ceremonies can become new ways to engage with the land.

On the day we visited the Rhinebeck natural burial ground, two people bicycled on the pathway through the woods. Although they’d heard the site was a cemetery, they were using it as they’d use any public park.

“Conservation is about people needing and caring for land,” Webster says. “They’re going to conduct life-affirming activities: Getting married there, baptisms, confirmations, bird-watching, hiking, family picnics—all kinds of things are happening in these spaces because they’re conservation spaces first. That’s the value of it.

“It’s not just that we’re going to put people in the ground without concrete. It’s about the big picture and how it affects people, the way we relate to death but also the way we relate to each other in life.”

There is disagreement within the movement on how best to grow. The values driving green burial suggest there should be more conservation cemeteries, but to meet that standard usually requires starting a new cemetery rather than converting or hybridizing an existing one. That costs a lot of money and requires securing new land and going through a complicated zoning process. To date, the Green Burial Council has certified only six conservation cemeteries in the U.S., compared to 35 hybrid cemeteries.

Cynthia Beal, of the Natural Burial Company in Eugene, Oregon, is a vocal proponent for converting existing cemeteries to natural burial spaces. That averts the zoning issue and provides an educational opportunity for the community.

“If you’re coming into a situation where the cemetery has been abandoned or poorly cared for and you make natural burial its new focus, you’re likely to have neighbors as advocates, happy to see the grounds renewed and the place cared for again,” Beal says. “Every cemetery is unique, telling its own stories of a community’s establishment and growth, and that history is also worthy of stewardship.”

Webster, for her part, is pragmatic about the challenge: While it would be great for more conservation cemeteries to come online, practices at local cemeteries should be improved in the meantime. That would also increase education and access.

“A sense of place is critically important to this,” she says. “I’m not going to [be driven] 300 miles to be buried in a green cemetery. My family is going to associate me with here, where we lived.”

Even in places like Rhinebeck that build at least partly on existing cemetery infrastructure, establishing green-burial sites takes time. Ramsey Creek Preserve was easier, Kimberley Campbell says, because South Carolina didn’t bother regulating. “I called down to the funeral board and got a delightful secretary,” Kimberly remembers. “She said, ‘The cemetery board has shut down. … I think what you are doing sounds marvelous, and there is absolutely nothing to stop you.’”

For Rhinebeck administrator Kelly, using municipal land didn’t require raising the $50,000 in trust for upkeep that is standard in many places. Still, it had to be planned, bid, surveyed, plotted, and certified, which took around five years.

The payoff of a natural burial ground can be big for a community. Gina Walker Fox, a Rhinebeck real estate agent, says she feels more comfortable with death for having bought a plot. (At 61, she recently asked a local quilter to sew her a raw-linen shroud, which she plans to embroider with a symbolic river.) Fox’s plot is near a blackcap raspberry bush she knows her adult children will want to visit.

“That old way—where people pick berries, sit, visit, picnic—that speaks to me,” she says.

Kelly laughs when we ask where she’ll be buried. She hasn’t picked or purchased a spot yet. Even a green-burial activist can feel like she has plenty of time to live.

“Once in a while,” she says, “I come by here and think I should probably get around to getting a plot.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!