Most of us have some strange ideas when it comes to grief.

I was five years old. I had just experienced what I assume was my first case of bullying. I was shocked and confused. I felt sad and angry. I was deeply disappointed.

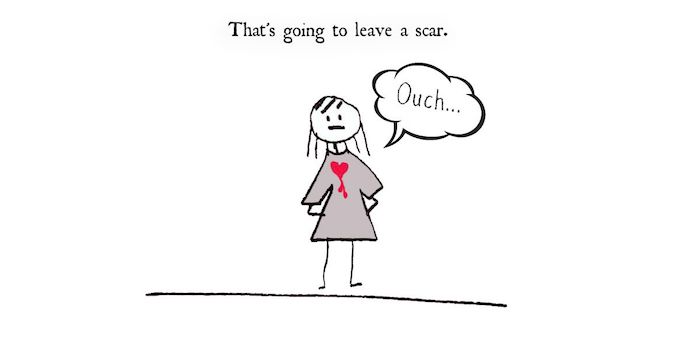

I had other disappointments before that, and I’ve had many since. More bullying, conflicts, failures, break-ups, rejections, estrangements, losses, and deaths. Each time, I experienced that heavy assault of shock, sadness, confusion, and anger. In some cases, the hurt went deeper, and bored its way into my heart. These deeper wounds came with added upset, anxiety, fear, and even depression.

I was grieving. In each case, something occurred that stunned my heart. I had lost something, or someone.

When we hear the word “grief,” most of us think of death. Grief, however, is the response of our hearts to any loss. Grief is everywhere, but it’s not a popular subject. It’s is one of those things we would rather not talk about.

When something isn›t talked about, a stigma often becomes attached to it. When it comes to grief, myths abound.

Here are five common myths about grief.

Myth #1: Grief is something to be conquered and overcome.

When we view grief as something to be conquered, we’ve labeled it an enemy. Like some unwelcome villain, it lurks in the shadows to trip us up and steal our happiness.

In reality, grief is a natural response to a loss of any kind, real or perceived. Our expectations are shattered. Life has surprised us. We’re hurt and wounded.

Grief is universal. Rather than something to be overcome, it is to be experienced and processed. We don’t conquer it, but move through it to heal and grow.

We have hearts. Grief is natural.

Myth #2: Grief is negative and we should get rid of it as soon as possible.

Because we associate grief with pain, we see it as inherently negative. No one wants it. Everyone flees from it. And if we›re in it, we want to get out of it as quickly as possible.

Painful things happen in life. If we don›t feel that pain, we become callous, bitter, and perhaps abusive. Denying or avoiding grief sets us up for a world of frustration and dysfunction.

Grief is actually positive. It declares that we have hearts. As we learn to process it in healthy ways, we discover our grief reveals what›s important to us.

Myth #3: Grief should be quick and easy.

We have this idea that grief should be over in a few days. If the loss is especially close or painful, perhaps a few weeks is acceptable. Anything more than that, however, and something is wrong. After all, life goes on. Better to buck up and get over it rather than waste away in sadness.

The truth is that grief has no timetable. Grieving isn’t a task to check off a to-do list. It’s a dynamic, somewhat unpredictable process.

Intense feelings surface. We suddenly find ourselves on an emotional roller-coaster full of unforeseen twists, climbs, and falls. This ride isn’t over in 90 seconds either. Grief is more of a marathon than a sprint.

Almost all the grief we experience is relational. Most losses tend to involve another person somehow. These losses hurt, and some can alter our personal worlds forever.

Most of us are grieving on some level. We’re constantly dealing with the results of what has happened to us. Grief is far from quick, and it’s never easy.

Myth #4: There are right ways to grieve.

If we must grieve, we naturally want to standardize the process. We want a recipe — a foolproof handbook for managing loss and hardship. We long for a checklist to measure our progress so that we when the last box is checked we can breathe a sigh of relief and say, “Done with that!”

We’re not robots. Each loss is unique. Circumstances, relationships, and hearts are all one-of-a-kind. Though there are patterns and similarities here and there, every single grief process is an individual adventure.

Though there is no right way to grieve, there are healthy and unhealthy ways of grieving. We learn, heal, adjust, and grow when we take our hearts seriously, practice good self-care, and stay connected to people who are helpful to us. If we instead choose to ignore and stuff our grief, it will leak out in ways we’ll most likely regret. Grief will be expressed, one way or another.

Grief is universal, but every grieving heart is unique.

Myth #5: Strong people don’t grieve.

We tend to confuse strong with stoic. Strength is synonymous with hard and impenetrable.

We’re not made of steel. Our hearts are not bulletproof. Strength doesn’t come from evading reality and ignoring emotions. We grow stronger as we face obstacles with the courageous resolve to do the grief work necessary to heal and grow.

Strong people are authentic and pursue integrity. What you see is what you get. They choose relational honesty over hiding. They grieve from the heart in healthy ways.

We love, and so we grieve.

Grief is natural and universal. It is a normal and healthy response to loss. When it comes, nothing strange or weird is going on. Grieving well, far from being negative, is the way we heal. It’s a process that takes time and effort. Each loss is unique and every person’s grief process is somewhat different. Grieving in healthy ways takes courage and internal strength.

Life is full of loss because it is also full of love. We love, and so we grieve. If you’re grieving today, please take your heart seriously. Look inside and process the hits well. Get around people who are helpful to you. Limit your exposure to critics and fixers. Be patient with yourself.

Many of us are hurting. Let’s grant one other the compassion we all need and long for. Grief is lonely, but the road of loss is well populated. Though we’re all unique, we can still travel together.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!