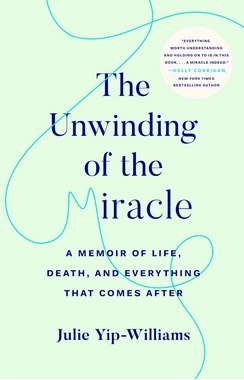

THE UNWINDING OF THE MIRACLE

A Memoir of Life, Death, and Everything That Comes After

By Julie Yip-Williams

By Lori Gottlieb

When we meet Julie Yip-Williams at the beginning of “The Unwinding of the Miracle,” her eloquent, gutting and at times disarmingly funny memoir, she has already died, having succumbed to colon cancer in March 2018 at the age of 42, leaving behind her husband and two young daughters. And so she joins the recent spate of debuts from dead authors, including Paul Kalanithi and Nina Riggs, who also documented their early demises. We might be tempted to assume that these books were written mostly for the writers themselves, as a way to make sense of a frightening diagnosis and uncertain future; or for their families, as a legacy of sorts, in order to be known more fully while alive and kept in mind once they were gone.

By dint of being published, though, they were also written for us — strangers looking in from the outside. From our seemingly safe vantage point, we’re granted the privilege of witnessing a life-altering experience while knowing that we have the luxury of time. We can set the book down and mindlessly scroll through Twitter, defer our dreams for another year or worry about repairing a rift later, because our paths are different.

Except that’s not entirely true. Life has a 100 percent mortality rate; each of us will die, and most of us have no idea when. Therefore, Yip-Williams tells us, she has set out to write an “exhortation” to us in our complacency: “Live while you’re living, friends.”

Before her diagnosis in 2013, Yip-Williams had done more than her share of living. It was, indeed, something of a miracle that she was alive at age 37 when she traveled to a family wedding and ended up in the hospital where she received her cancer diagnosis. Born poor and blind to Chinese parents in postwar Vietnam, she was sentenced to death by her paternal grandmother, who believed that her disability would bring shame to the family and render her an unmarriageable burden. But when her parents brought her to an herbalist and asked him to euthanize her, he refused.

The family would eventually survive a dangerous escape on a sinking boat to Hong Kong, and less than a year later make their way to the United States, where at 4 years old, Yip-Williams had a surgery that granted her some vision, if not enough to drive or read a menu without a magnifying glass.

The family would eventually survive a dangerous escape on a sinking boat to Hong Kong, and less than a year later make their way to the United States, where at 4 years old, Yip-Williams had a surgery that granted her some vision, if not enough to drive or read a menu without a magnifying glass.

She would go on to defy her family’s expectations, eventually graduating from Harvard Law School, traveling the world solo and working at a prestigious law firm where she meets Josh, the love of her life. She becomes a mother and, soon after, a cancer patient, and soon after that, because of this unfortunate circumstance, a magnificent writer.

During the five years from her diagnosis to her death, we enter her world in the most intimate way as she cycles through Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s famous stages of grieving: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Describing the ways in which terminally ill patients cope with their own deaths, these stages weren’t meant to delineate a neat sequential progression but rather the various emotional states a dying person might visit, leave and visit again.

Yip-Williams toggles between optimism and despair, between believing she’ll defy the statistics as she had so many times in her life — “odds are not prophecy” — and trying to persuade her husband to confront their harrowing reality. She makes bargains with God, just as she did as a young girl when, in exchange for her poor vision, she asked for a soul mate one day. (“God accepted my deal!”) She posts pictures of contented normalcy on Facebook — of meals cooked, a car purchased — but rages at her husband, healthy people, the universe and, silently, at the moms at a birthday party who ask how she’s doing. “Oh, fine. Just hanging in there,” she replies, while wanting to scream: “I didn’t deserve this! My children didn’t deserve this!” She frets about the “Slutty Second Wife” her husband will one day marry and the pain her daughters will experience in her absence. And, near the end, she oscillates between being game to try every possible treatment and accepting that nothing will keep her alive.

“Paradoxes abound in life,” Yip-Williams writes in a heart-rending letter to her daughters; she asks us to confront these paradoxes with her head-on. One of the paradoxes of this book is that Yip-Williams writes with such vibrancy and electricity even as she is dying. She moves seamlessly from an incisive description of her mother as “the type of woman who sucks blame and guilt into herself through a giant straw,” to the gallows humor of “Nothing says ‘commitment to living’ quite like taking out a mortgage,” to the keen observation “Health is wasted on the healthy, and life is wasted on the living.” Unlike the woman in her support group who, after being given a terminal prognosis, defiantly declares, “Dying is not an option,” Yip-Williams prepares meticulously for her death while paying close attention to the life she will one day miss: “the simple ritual of loading and unloading the dishwasher. … making Costco runs. … watching TV with Josh. … taking my kids to school.”

This memoir is so many things — a triumphant tale of a blind immigrant, a remarkable philosophical treatise and a call to arms to pay attention to the limited time we have on this earth. But at its core, it’s an exquisitely moving portrait of the daily stuff of life: family secrets and family ties, marriage and its limitlessness and limitations, wild and unbounded parental love and, ultimately, the graceful recognition of what we can’t — and can — control.

“We control the effort we have put into living,” Yip-Williams writes, and the effort she has put into it is palpable. Of all the reasons we’re drawn to these memoirs, perhaps we read them most for this: They remind us to put in our own effort. It would be nearly impossible to read this book and not take her exhortation seriously.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!