We often use technology to form meaningful relationships with virtual strangers. But what happens when the person on the other side of the screen dies?

By Cindy Lamothe

Last November, Kristi Pahr felt both shock and denial after learning that her online friend of over four years, Amy, had died suddenly. She says she still cries remembering those initial days of grief. Amy, she said, “was a better, more ‘real’ friend to me than most people I know in person.”

Ms. Pahr, 41, a freelance writer from South Carolina, first met Amy through mutual friends in an online Star Wars game back in 2013. She fondly recalls a similar “geekiness” and love of fantasy novels quickly bonded the two. “We chatted every day, shared pictures of our kids,” complained about their spouses. And though she and Amy knew each other only virtually, their daily texts evolved into years of mutual support and understanding. “She encouraged me to start submitting my writing for publication,” Ms. Pahr said, “and was one of the only people I ever let read the things I wrote before I was published.”

Today around 70 percent of Americans connect over social media, according to the Pew Research Center. Although many of us are talking to people we know in real life, it’s easy to form connections with people we have never met in person.

More than ever before, we are using our smartphones and technology to form meaningful relationships with virtual strangers, both in romance and friendship; we celebrate one another’s successes, share our individual struggles, and despite geographical limitations, these bonds often span years. But what happens when the person on the other side of the screen dies?

Finding out about her friend’s death last fall was devastating, said Ms. Pahr, who recalls scrolling through her newsfeed one day and stumbling upon a post from someone outside of her contacts offering condolences to Amy’s family. “I was dumbstruck and thought it must’ve been a mistake.”

She remembers frantically messaging Amy soon after, and waiting for the “read” indicator to pop up next to the message — only to have it remain unanswered.

“Days passed and I still waited,” she said. “I kept expecting to find out it was a different person, or that someone had been wrong.” Not knowing what else to do, she eventually reached out to Amy’s husband by messenger, who confirmed her friend had passed away. “I was a disaster for a while, randomly crying throughout the day.”

Our ideas about which relationships are “real” have not caught up with the ways we actually live and connect, said Megan Devine, a Portland-based psychotherapist and author of “It’s OK That You’re Not OK.” She’s adamant that this deep sense of loss isn’t limited to in-person friendships.

One of the difficulties Ms. Pahr faced after Amy’s death was a lack of empathy from others. “Even well-meaning and compassionate people don’t place the same weight on your grief,” she noted, the way they would if you lost a friend you knew in person.

“Grief is often unacknowledged in western culture, no matter what the cause,” Ms. Devine said. In fact, the societal norms around grieving cyber relationships is still relatively new, and to this day, remains largely unexplored. “When you add in the non-corporeal relationship, the pain can be even more invisible.”

This can often lead people to experience what psychologists call “disenfranchised grief,” a term coined in 1985 by Dr. Kenneth J. Doka to describe a loss that isn’t acknowledged by others. As he explained in his book “Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Hidden Sorrow,” these losses can often deprive a person of the catharsis found in shared bereavement. “You don’t really have a socially sanctioned right to grieve,” said Dr. Doka, who teaches gerontology at the College of New Rochelle in New York. “But these relationships can be very profound.”

Understanding the unique challenges of cybergrief can validate how a person may be feeling. Here are five ways of coping with the loss of an online friend.

Don’t Dismiss It

“In many ways, the grief is twofold,” said Dr. Kathleen R. Gilbert, author of “Dying, Death, and Grief in an Online Universe,” because a person isn’t only grieving their loss, they’re also grieving for the loss of support they had hoped they would receive from other people. Often times, Ms. Devine explained, it’s our in-person friends or family who can be confused or dismissive of our grief. But, she emphasizes, the first step forward is to acknowledge that all relationships are important, whether we see someone physically or not.

Claim Your Grief

One of the things the internet does is expand our awareness of the world beyond the corporeal one we know. Social media allows us to develop a construct of another person, their hopes and dreams — and similarly, share our own. Many of us have spent years cultivating relationships based on words and images.

This has been true for Ms. Pahr: “Friendships and what it means to be friends has changed so much in the last 20 years,” she said. “The fact that you can be BFFs with someone without ever hearing their voice or touching their skin is mind-blowing to some people.”

Cyberloss isn’t any less genuine or deeply significant simply because the interactions took place online. As Ms. Devine explains, every grief is valid, and just because you aren’t in the same room, or connecting over tea in your home city, doesn’t mean you don’t rely on the person, or count them among your inner circle. “The only person who gets to decide what grief looks like is the person experiencing it.”

Gently Reach Out

Whether or not we should contact the person’s family with our condolences can be tricky. On the one hand, we want to express how much they meant to us, but we’re also wary of intruding.

Ms. Devine encourages gently reaching out to the family or friends of the person with a quick message or email sharing a favorite memory, and letting them know we join them in wishing things were different. Family members may not recognize your message in the initial days and weeks after the death, “but many people take great comfort in learning how vastly loved their person is.”

When it comes to attending the funeral, she cautioned that there are boundaries to keep in mind. While everyone has a right to grieve, if we aren’t in the epicenter of the loss — as in immediate relatives and loved ones — we might feel less recognized at in-person events like memorials or funerals. Even so, attending them shouldn’t be ruled out altogether. Go if it feels right, Ms. Devine suggested, but do not shove your way into the inner circle. “Your relationship is valid, but it’s different from the partner, parent, child, sibling, etc.,” she said.

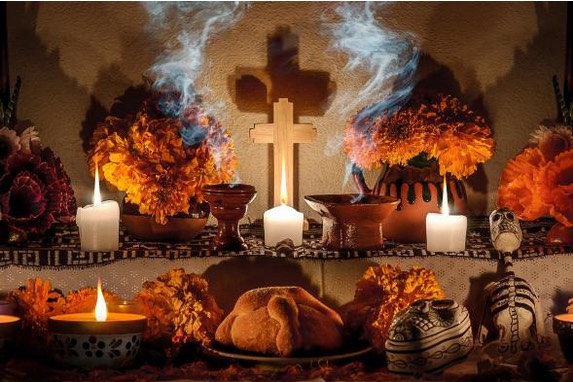

Create a Ritual

The hardest task of mourning is to accept the reality of the loss, said Julia Samuel, a London-based psychotherapist and author of “Grief Works: Stories of Life, Death, and Surviving.” If someone is an online friend, she explained, there may be less concrete experiences or objects on which to focus one’s grief, which could make it hard to really believe the person has died. She advises the importance of creating a ritual that represents an ending, whether by lighting a candle and saying a prayer or poem, or going to a place of worship to do something similar. Dr. Gilbert likens this to a ritual of transformation: “The person is no longer available to me, but I can still have in my heart a connection with them.”

Find Your People

While the pain of grief may lessen over time, Dr. Doka noted that we never really get over a loss, we learn to live with it. That includes cybergrief. “Even years later, people can have surges of grief,” he said. Though it will feel difficult at times, finding support through a trusted counselor or online bereavement community can be an invaluable way of receiving the validation we need.

Of course, creating relationships — online and off — that are based on care, support, kindness and empathy are your best resource, adds Ms. Devine. Investing in all of those friendships is your best insurance, “that way, no matter what happens, you have a net to surround and support you.” As Ms. Samuel put it, “What we need most when someone we love has died is the love of others.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!