When to step in — and how to guide their financial future

[I]n the year 2011, the Baby Boomer generation started turning 65. Over the next 13 years, 10,000 Boomers will reach retirement age every day.

For the adult children of the Baby Boomers, these are not abstract statistics but real-life turning points that can provoke uncertainty and anxiety. But consider the advice of certified financial planner and author Lise Andreana:

“There is no time like the present to begin preparing for your aging parents’ financial future. Being proactive can help minimize a great deal of stress and uncertainty down the road — for your parents, yourself, and your entire family.”

The Simple Dollar is here to help you begin the journey of guiding your parents through this stage of their lives. We’ll cover how to approach the conversation, documents you’ll need, costs to consider, and more. Let’s get started.

Table of contents

Broaching the subject

Power of attorney

Document checklist

Long-term care costs

The sibling situation

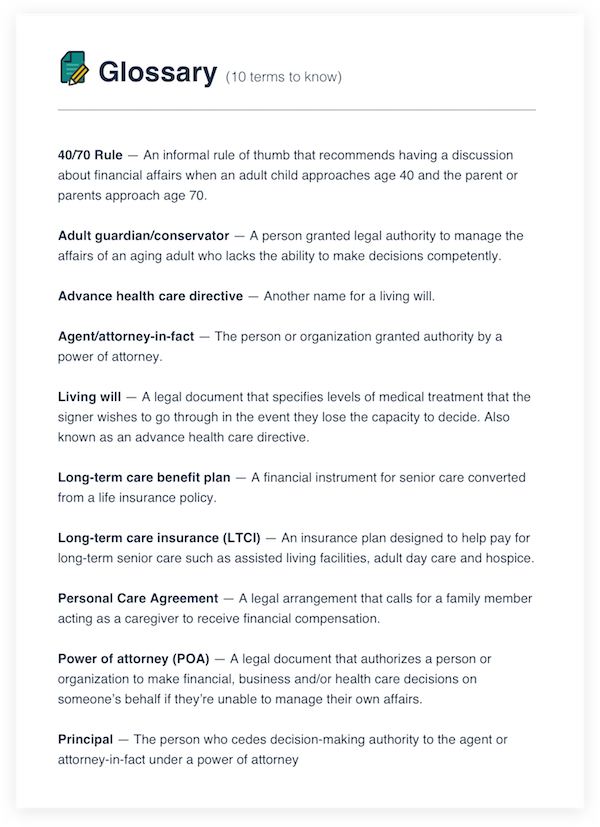

Glossary

Additional resources

The Talk: How to handle a sensitive subject

Every family is different, and yours may have its own quirks or hangups about money. Although no size fits all, here are some suggestions on having The Talk with your parents:

When is the right time?

Many senior care experts recommend following the 40/70 Rule. As you approach 40 and your parents approach 70, it can be the most opportune time to discuss financial issues, as well as long-term care, estate planning and other relevant topics.

It’s better to address the situation proactively than to wait for a crisis to unfold, which could force your family into making decisions on the fly.

Are my parents already having trouble?

Be on the lookout for warning signs that your parent may be struggling to manage his or her finances, which can include:

- Unpaid bills

- Bounced checks

- Calls from creditors

- Unusual or frivolous purchases

What’s the right approach?

To help prevent conflict with your parents when you talk about finances, consider the following.

- Keep the circle small.

Discussions involving a few key people can be less intimidating than a full-blown family meeting that could leave your parents feeling like you’re ganging up on them. - Focus on positives, not negatives.

Don’t frame your concerns in terms of physical or mental decline. Keep the focus on a bright future for the entire family. - Treat them as peers and equals.

Help your parents understand that you’re trying to look out for them, not look after them. Invite them to join an ongoing conversation. - Find an ally.

Your parents might be more receptive if your family attorney or financial planner joins the discussion in the role of an objective third party. - Make a show of solidarity.

This subject presents an opportunity to do a thorough check of your own finances to see that everything’s in order. This way, your parents might not feel that you’re singling them out or passing judgment. - Avoid fighting words.

Certain words and phrases — including always, never and nothing — have a tendency to put people on the defensive and shut down communication. It can happen in any kind of personal relationship, including parent-child.

When in doubt, preserve your parents’ dignity. Be aware of the potential for wounded pride — speak respectfully and tread lightly.

Expert opinion

“Start the conversation early. Put in place a plan your family can follow when your parents can no longer make decisions on their own. … It’s important to ask questions and help your parent come to a decision on his or her own terms.”

Terri Rasp

Director of Sales, Analytics, and Training

StoneGate Senior Living, LLC

Power of attorney

A power of attorney, also called a POA, is a legal document that grants a person or organization (known as the agent or attorney-in-fact) the authority to act on behalf of someone (the principal) in specific financial, legal and health-related matters.

A POA with you as the agent and your parent or parents as principal could play an integral role in helping you protect their financial well-being. With a power of attorney in place, you will be able to act quickly if a parent suffers a medical emergency, for example, or experiences a steep decline in mental competence.

Should I use a lawyer for a POA?

The answer is, most likely, yes. You don’t necessarily have to go through an attorney, but it’s probably the wisest course of action. The power of attorney process can vary from state to state, and trying to go it on your own could result in a costly oversight.

Unless you’re an attorney or a financial adviser, you may not have the expertise to navigate these waters. Also important is the fact that a professional often brings some much-needed objectivity to a situation where emotions can cloud the issues.

Can I get a POA on my own?

Some legal advice websites let you download a printable version of your state’s POA form. However, bear in mind that you’re dealing with the complexities of legal documents and contracts. There’s no shame in seeking the advice of your family attorney, your financial adviser, or both to help you craft a POA that addresses your family’s specific needs.

What’s the best time to get a POA?

The key factor in a child-parent power of attorney is obtaining it proactively, before the parent loses the ability to manage their own affairs.

What kind of POA should I get?

A lot depends on the current status of the parents and when the family wants the POA to take effect. An attorney may recommend a durable power of attorney, which contains a durability provision to ensure it remains in effect if the principal’s condition changes. The change in status could be a sudden medical issue that leaves the parent debilitated or a deterioration in mental capacity.

A power of attorney covering financial affairs differs from a health care POA, which means you’ll need to address those issues separately.

What if my parent has dementia or Alzheimer’s?

Depending on the laws of your state, getting a POA for a parent who has dementia or Alzheimer’s disease may require a letter from a physician affirming that your parent understands what the POA means and can legally consent. If a parent is deemed unable to meet that standard, another option may be for the child to become an adult guardian or conservator instead — a process that would require a judge’s approval.

Is a power of attorney the same as a living will?

No, there’s a difference. A living will expresses the signer’s wishes regarding medical treatment in the event he or she loses the capacity to make decisions (for example, whether extraordinary measures should be taken to preserve their life or resuscitate them). This kind of document is sometimes called an advance health care directive.

As with a power of attorney, state-specific versions of living wills are available online. Still, it’s wise to consult an attorney about the specifics of your situation.

Obtaining power of attorney: 3 key steps

Expert opinion

“Prior to cognitive decline, I advise my clients to help their parents establish the proper paperwork. This includes the creation of a will, durable power of attorney, health care power of attorney, and advanced directives. The power of attorney forms are very powerful documents that should only be in the hands of somebody your parents trust. Whether that is a family member or a professional, it is up to them.”

Nate Byers

CPA/PFS, MBA

JBC Wealth Advisors, LLC

Financial document checklist

Here’s a list of important documents for reviewing a parent’s finances. These records will help you get a better idea of income and financial obligations. Double-check this list with your financial adviser to see if anything needs to be added.

_ Bank accounts

_ Credit card statements

_ Monthly bills (utilities, rent/mortgage, subscriptions, etc.)

_ List of loans and other debts

_ Social Security statements

_ Social Security benefit verification letter

_ Pension, 401k and annuity documents

_ Tax returns (for three to seven years)

_ Investment documents (savings bonds, stock certificates, brokerage accounts, etc.)

_ Insurance policies — life, health, and property

_ Vehicle titles

_ Property deeds

_ Dues-paying memberships (HOA, AARP, clubs, etc.)

_ Birth certificates and marriage licenses

Don’t forget …

_ List of their usernames and passwords for online customer portals

_ Combination/keys to their safety deposit boxes

Expert opinion

“The first thing that children should do is to start aggregating information on the parents’ financial information. Help your parents consolidate their holdings. Fewer bank accounts can save you tons of time.”

Scott W. Johnson

Owner, WholeVsTermLifeInsurance.com

Long-term care costs

When looking at long-term care solutions, be aware that private insurance and Medicare have some limitations. While Medicare and insurance do provide coverage for medical treatment and prescription drugs, custodial care such as long-term care facilities and home health care may be a different story. As a 2013 study points out, Medicare:

- Pays only for “medically necessary care in a skilled nursing facility” — which is not the same as an assisted living center.

- Pays for home health care “under very limited circumstances and for brief stretches of time.”

In some unfortunate cases, coverage gaps in Medicare and private insurance can lead to families exhausting financial resources (known as “spending down”) until their parents qualify for Medicaid. To help prevent this worst-case scenario, you may want to consult a financial planner about some proactive options such as:

Long-term care insurance (LTCI)

Expenses covered by long-term care insurance generally include assisted living, nursing home, adult day care, Alzheimer’s care facilities and hospice. The key is encouraging parents to buy coverage early, before they develop health problems.

Pros and cons include: LTCI can be pricey, although it could cover some expenses that Medicare or private insurance do not.

Long-term care benefit plan

This option involves converting a life insurance policy into funding specifically for long-term care. These insurance conversions are also called life care assurance, Medicaid life settlement, or life care funding. It’s commonly used as part of a spend-down strategy to receive Medicaid eligibility.

Pros and cons include: This strategy can provide an immediate source of funding. However, the family will lose the death benefit that an unconverted insurance policy would have provided.

Reverse mortgage

Some aging homeowners turn to reverse mortgages (also called home equity conversion mortgages) to turn their equity into cash while still retaining ownership.

Pros and cons include: Although it can provide a cash infusion, using a reverse mortgage to pay for senior care is a potentially risky, “last resort” type of move. Not everyone will qualify, and defaulting could lead to loss of ownership.

Medicaid

Unlike Medicare, Medicaid is jointly administered by the federal government and individual state governments. As a result, eligibility requirements and other rules vary from state to state.

In general, though, Medicaid recipients must have low incomes and assets with very low value. The program is intended to benefit the poorest Americans, so many middle-class families likely don’t qualify.

To get more information, check with the agency that manages Medicaid in your state. You can also contact an elder law attorney in your state or visit these websites:

Claiming your parents on your tax return

To claim a parent as a dependent, your financial support for them must be substantial — at least 50% of the total cost for housing, food, medical care and other items. Also, the parent can’t earn more than the personal exemption for that tax year (which was $4,050 in 2016).

So, unless your parent has a very low income and you pay more than half the cost of keeping them cared for, they probably wouldn’t qualify as a dependent. If the parent does qualify, you could receive tax benefits such as the Dependent Care Tax Credit and reduced taxable income.

To get definitive answers, ask your tax preparer. You can also call the IRS or make an appointment at a local Taxpayer Assistance Center.

Expert opinion

“When budgeting for an aging parent, Medicare costs need to be factored in. They pay a monthly premium for Medicare Parts B and D for life and then also a Medigap or Medicare Advantage plan to pay for the things like deductibles and coinsurances that Medicare doesn’t cover.”

Danielle Kunkle

Co-founder, Boomer Benefits

The sibling situation

Among adult siblings, the care of aging parents has the potential to spark conflict like few other subjects. Handling parents’ finances is no exception.

It’s not uncommon for someone who takes the lead as caregiver to feel overburdened and resentful toward a sibling taking a less active role. Fortunately, a personal care contract or caregiver agreement can help ensure that the sibling who makes the most sacrifices is at least financially compensated.

Under this type of agreement, parents or other family members agree to reimburse the family member acting as caregiver. Compensation options include:

- Direct payments (the income will be taxable)

- An estate plan, or additional consideration in the parent’s will

- Transferring homeownership to the caregiver

- A life insurance policy with the caregiver as beneficiary

An elder law attorney can help you draw up a caregiver agreement. As for the form that compensation takes, families should think carefully about options that could lead to future conflicts between siblings (specifically, an estate plan or home transfer).

About those conflicts…

Even if you have a financial arrangement in place, don’t forget that sibling caregivers often have emotional needs in addition to financial ones. Expert tips on how to defuse conflict and increase support include:

- Stay in communication, even if it’s just a weekly call

- Arrange for someone else to step in every now and then so the caregiver can have time off

- Ask for outside help (family counselors, social workers, clergy, etc.) when conflict becomes unmanageable

Expert opinion

“Personal care agreements are valuable for two very different reasons. One is emotional, for the family caregiver to feel as though they have a ‘real’ job and have at least a written record of what they need to do. Many have to cut back on work or stop working during a period of caregiving. The agreements can also serve as a record of the work done for siblings.”

Michael Guerrero

Senior Benefits Adviser

Elder Care Resource Planning

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!