As owners tout benefits and usage in compassionate care, the battle for legalization mirrors humans’ own medical marijuana fight in 1990s California

By Josiah Hesse

Bernie, a 130-pound Swiss mountain dog, began having grand mal seizures when he was six months old. About once a week he would violently convulse, foam at the mouth, and urinate on himself for several minutes before recovering an or so hour later. The medication he was given seriously disoriented him, was harmful to his liver and for the most part didn’t work.

At the end of their rope, Bernie’s parents decided to put him on a pet supplement derived from cannabis. Gradually, his seizures became less severe and less frequent, before disappearing altogether.

Despite a large amount of promising anecdotal evidence like Bernie’s story, and a growing industry of cannabis-based pet products, many people have a hard time taking medical marijuana for pets seriously.

“It sounds ridiculous, until you experience it yourself,” said Bernie’s owner, Anthony Georgiadis, who says his dog hasn’t had a seizure in four months.

Living in Florida, where medical marijuana is illegal, Georgiadis orders Bernie’s supplement online from a California company called Treatibles. He is allowed to do this because Treatibles products are derived from legal hemp and contain little to no THC (the intoxicating ingredient in marijuana).

Many pet products are not made from hemp, though, but rather straight marijuana containing trace amounts of THC. So anyone wanting these products for their animal’s chronic pain, anxiety, inflammation, appetite stimulation, or epilepsy have to live in a state where medical marijuana is legal – and even then, they need to have a prescription for themselves just to enter a dispensary.

Last year, Tick Segerblom, a Nevada state senator, introduced a bill to create a medical marijuana registry for pets.

“They thought it was a joke,” Segerblom said of his senate colleagues. “It was the talk of the country for a while.”

“Look at this moron!” Dennis Miller screamed on the O’Reilly Factor, deriding the senator’s bill, calling it “the end of culture as we know it”.

“I have fish at home that want medical marijuana,” O’Reilly joked. “I’m not exactly sure how to deliver that to them, because if you put the cigarette in there it all gets wet.”

Despite the public ridicule, Segerblom said, he had been looking forward to the issue being debated in a hearing, but that hearing never happened. In the end, he said, “it went to a committee headed by a person who hates marijuana, and he made sure that it died”.

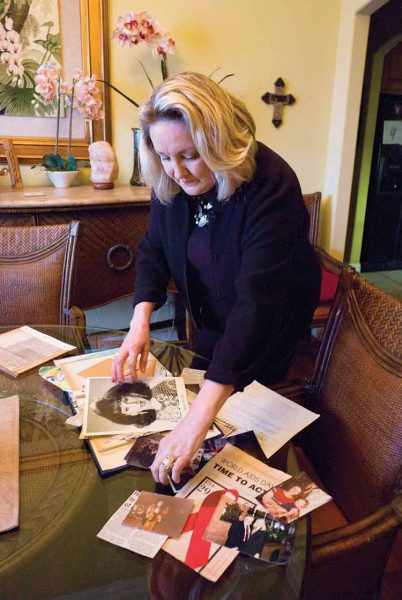

Amanda Reiman, manager of marijuana law at the Drug Policy Alliance, said that today’s battle over animal medical marijuana mirrors the clash over human medical marijuana in 1990s California.

“When we first started talking about the idea of using marijuana as a medicine, people laughed about it,” she said. “But they’ve come around, because when you know someone who was helped by cannabis it’s not funny anymore.”

n 2013, Reiman’s cat, Monkey, was diagnosed with terminal intestinal cancer. The chemotherapy and medication caused Monkey to lose her appetite, not sleep and become lethargic. The situation reminded Reiman of the countless scenarios she’d encountered with humans after a decade of working in medical marijuana, so she decided to mix a very small amount of cannabis oil in Monkey’s food.

“It brought her energy back, she was eating and playing – she was actually acting healthier than she had been before she was diagnosed with cancer,” Reiman said. “I knew it wasn’t a cure for her, and in the end she passed away several months later. But I really do feel it gave her a quality of life at the end; instead of just fading away, she stayed strong right up until the end.”

Veterinarians caution against pet owners taking matters into their own hands, because finding the correct dose can be tricky. While many pet medicines are just human drugs in different doses, the weight ratios between humans and animals can make it easy to accidentally give your pet an overdose. And pets overdosing on cannabis is already a serious problem in states where marijuana is legal.

As with children, it’s common for pets to stumble upon a high potency marijuana edible, eat it, and become incredibly ill and intoxicated.

As with children, it’s common for pets to stumble upon a high potency marijuana edible, eat it, and become incredibly ill and intoxicated.

“We’ve seen some serious poisonings of animals [from marijuana] and even a couple of deaths,” says the medical director at the ASPCA Animal Poison Control Center, Dr Tina Wismer.

When it comes to pet meds, Wismer says it’s not uncommon for a human medication to be applied to animals purely on the basis of anecdotal evidence. She believes more studies need to be done on the therapeutic use of cannabis on animals to find the right dose.

Dr Sarah Brandon, a veterinarian and cofounder of Canna Companion, a hemp-based pet supplement company, says that over the last 18 years, she has administered cannabis to more than 4,000 animals, and is currently analyzing data before offering it to the medical community.

“Right now, veterinarians have no guidance on this,” she says. “There’s a lot of fear out there, and they are scared to come out and recommend [cannabis]. A veterinarian can recommend a hemp-based product as a supplement, but they cannot encourage them to use marijuana.”

Dan Goldfarb, owner of Seattle-based Canna-Pet, describes the differences between hemp and marijuana: “It’s like dog breeds: you can have a chihuahua or a great dane, both of which are dogs but are bred to exude very different characteristics.”

Canna-Pet, Treatibles and Canna Companion are all strictly hemp-based, so they are allowed to sell their products outside of marijuana dispensaries – even online to states where marijuana is illegal – without the need of a prescription. This also affords them deniability when people like Dennis Miller say they just want to get their pet stoned. But there are a handful of companies who use straight marijuana in their pet products, who say that hemp is too limited.

“We’ve seen better results with a little THC,” says Alison Ettel, founder of Treat Well, who has been using cannabis on a variety of animals for ten years and was recently invited to treat seals at the Marine Animal Center in Sausalito, California. She says that hemp works for some ailments like anxiety, but doesn’t contain a number of medicinal properties that marijuana does, like appetite stimulation, and that hemp can be harmful to an animal with a compromised immune system. “We believe hemp can have more negative effects than positive.”

Ettel adds that while her products contain psychoactive properties, if used in the right dosage in proportion to the animal’s size, there is no reason they should ever become intoxicated by it.

Brian Walker’s California company, Making You Better Brands, offers a marijuana based doggie shampoo for pain relief (along with similar products for horses). Walker says that the marijuana is never activated with heat, a process necessary for making the plant psychoactive.

But his company is still regulated like any other in the cannabis industry, meaning pet owners can only buy it in a dispensary with a (human) prescription, and can’t take it out of state. Walker said the lack of information available about the differences between hemp, active cannabis and inactive cannabis has prevented acceptance among veterinarians of medical marijuana.

“They picture a dog eating a brownie and being high for two days,” he said. “But with non-active cannabis they’re not going to get high – they’re going to get well.”

Complete Article HERE!