By Lauren O’Neill

The first time my granddad didn’t recognize me wasn’t as bad as I expected it to be. He greeted me with warmth like always, except he didn’t call me “Lauren” or “love” but “son.” “Hello, son,” he said to me in the stubborn Dublin accent that years of living in England could not uproot. “How are you?” He was looking right at me, but he didn’t know who I was, and that was that.

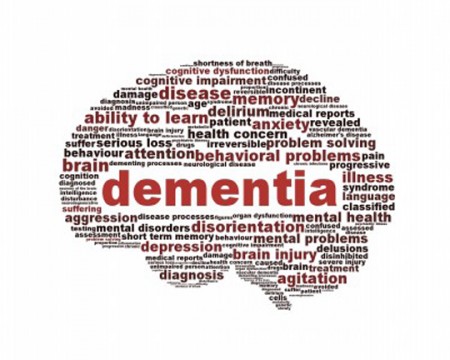

When my granddad was initially diagnosed with dementia, my first predictably selfish response was to get really scared about him forgetting who I was. But when it eventually happened, it kind of just happened, the way that dementia itself just happens—quietly, with very little fanfare. It slips its thin, invisible fingers around sufferers’ throats, wringing out the personhood so slowly that in the beginning, you don’t even notice it. I didn’t cry like I thought I would when my granddad didn’t recognize me, because over time I had just got used to the idea that one day, he wouldn’t. When someone close to you gets dementia, you are forced to resign yourself to the plain fact of degeneration; it is a terrible thing to “just get used to,” but currently no cure exists, so getting used to it is all you can do if you’d rather not get sucked into an existential thought vortex concerning the cruelty, fragility, and ultimate futility of human life.

I don’t mean to be cynical. I know that if my granddad could read this, he would disagree with that last bit: For him, while he was well, life had a lot of meaning. He was a pretty committed Catholic, and a guy who, in general, enjoyed being a human person living in the world. For most of his life he ran pubs in Birmingham, and when he gave that up, he and my nan, whom he adored (and who now makes the two-train trip across the city to see him in his nursing home almost daily, with a dedication that only a woman who has been in love for more than 50 years could muster), went on loads of those cruises for people who have retired where there are rock-climbing walls on the ship. He was funny, and really good at mental arithmetic, and he liked singing IRA songs and drinking pints of Guinness. He had, especially in later life, a properly good time.

So when he started becoming forgetful, and when his wit got a bit duller than it had been before, nobody really thought anything of it, because he just wasn’t the type of person who would ever get a condition like dementia. He was too robust, too aggressively healthy in his old age, too different from the type of frail, elderly person we tend to commonly associate with dementia—he was just getting old. And even after a severe dissociative episode during a holiday in Spain, when he became convinced that he was sharing a bus with terrorists, and told hotel receptionists that my nan was trying to kill him, his GP diagnosed a nervous breakdown long before considering the possibility that the problem could be rooted in a degenerative disease. He simply was not that kind of man. Even the doctor thought so.

But of course, he was that kind of man, because any man can be that kind of man. Dementia can happen to literally anyone, regardless of physical health, though some people are more genetically predisposed to it than others. It is caused by some very complicated and very fucking scary and bad-sounding shit happening to your brain, and has some pretty horrific symptoms. In general, you gradually get worse at doing anything at all for yourself, turning previously simple daily tasks like going to the toilet and getting dressed into missions requiring approximately the same amount of organization and personnel as a moon landing. You lose your memory, to the extent that you start to forget some words. Eventually, you even forget how to move, and become bedbound. After that, your immune system packs in, and once that happens it’s kind of game over. Dementia, one; you, very much nil.

I had never considered having to deal with any of these symptoms, because the grandparents whose home I grew up in seemed so youthful for so long. Degenerative diseases were, to my mind, obviously terrible but ultimately distant, like wars on the news or something. Until my granddad got sick, the closest I came to dementia and its related conditions was via a great-uncle I didn’t really know, who died unusually young of Alzheimer’s. But then, after the incident in Spain, dementia’s spindly hands began to take hold of my granddad really quickly. I was 18, and had come home from my first term at university to a house where people had to take it in turns to sleep because my granddad had started pacing around every single night until dawn, the confusion in his head now torturous.

It is difficult to get used to the idea of someone who raised you needing to be looked after so thoroughly. It is even more difficult to become one of the people doing the looking after. My granddad was integral to my upbringing—I have lived in his house at numerous intervals during my life (I’m back here now, writing this), and he always nurtured me. It is weird, small things that I remember best, like how he made me watch Countdown with him so that I’d get better at spelling, and how carried me on his shoulders when he fetched me from school. Dabbing the side of someone’s mouth with a piece of kitchen roll after they drink a cup of tea is hard when you know that they used to clean up your baby sick, because you used to rely on them, and now they rely on you. It’s life, and it happens, but isn’t it fucking sad?

It is difficult to get used to the idea of someone who raised you needing to be looked after so thoroughly. It is even more difficult to become one of the people doing the looking after. My granddad was integral to my upbringing—I have lived in his house at numerous intervals during my life (I’m back here now, writing this), and he always nurtured me. It is weird, small things that I remember best, like how he made me watch Countdown with him so that I’d get better at spelling, and how carried me on his shoulders when he fetched me from school. Dabbing the side of someone’s mouth with a piece of kitchen roll after they drink a cup of tea is hard when you know that they used to clean up your baby sick, because you used to rely on them, and now they rely on you. It’s life, and it happens, but isn’t it fucking sad?

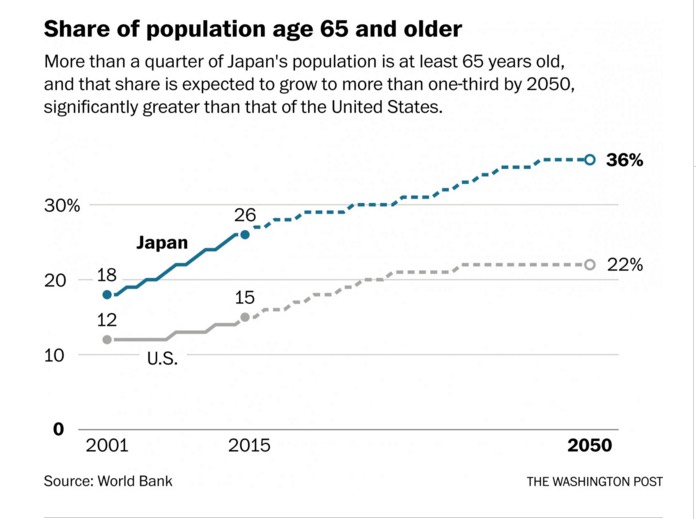

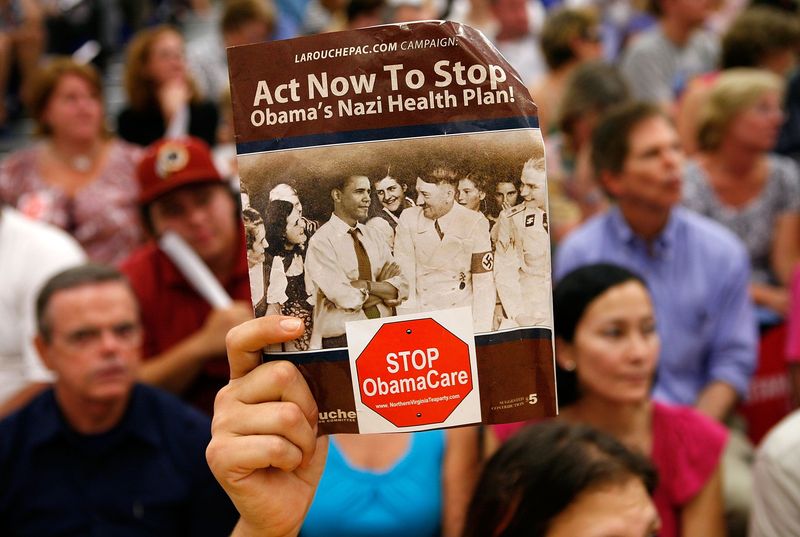

Dementia now affects an estimated 850,000 people in the UK, with the number expected to reach a million by 2025, which means that a lot of people reading this probably have firsthand experience of how fucking sad it is. But still, we don’t really talk about it, and I think that’s because it’s a disease that forces us to confront our most basic, human fears—like losing your dignity, or becoming a burden to the people you love, or even not knowing who or what you are. Because fundamentally, ego is what makes us human, and dementia takes that very human self-interest away, drip by drip. The grim vastness of that is terrifying; it’s no surprise that we don’t really want to discuss a disease that has the potential to chew us as if we’re tough pieces of meat, for a very, very, very long time, before eventually swallowing us forever.

Before necessarily succumbing to it, those who are unlucky enough to end their days with dementia usually go to live in nursing homes, because they need the kind of specialist, around-the-clock care that most families just can’t provide. Nursing homes are not an-body’s favorite places, and my granddad’s, despite its cheery purple decor, is no exception. Sadness looms on its corridors like humidity—never suffocating, but always palpable. It clings to the curtains, the walls, the sticky laminate flooring, the people. The friendly staff, mostly women of varying ages, do their best on a low wage, kindly chatting to the patients whose pasts, behaviors, likes and dislikes they have gotten to know well as they flit about the ward wearing disposable plastic aprons, from which fluids of various kinds can be wiped away. The armchairs in the lounge are tall and straight-backed to discourage slouching; the bedrooms are large and practical and beige.

The walls of my granddad’s bedroom are covered in photos of family members whom he mostly doesn’t recognize. He knows my nan mainly by the sound of her voice, and even then his acknowledgement of her can wane from visit to visit. But there are still good days, when little rays of joyful humanity emit from him. When he gets a lot of stimulation from the staff or from visitors, there is still so much of my granddad that the illness has not been able to sap away yet. He comes to life when he hears music and is still a boisterous and enthusiastic singer; he dances and plays football, and receives visits from the local priest, who says prayers with him. All of this is, obviously, extremely cool to see. Equally, though, there are bad days. He can be angry, and anxious, and sometimes both. His life as a publican haunts him on those days, and his cloudy mind becomes fixated on money and work. If he doesn’t get the answers he wants, he can become moody and aggressive for entire days. His mood can change in the blink of an eye, and when I go to visit him, I never know which side of him I’m going to meet that day.

But I guess I’m not the only one. These days, there are an awful lot of people affected by dementia, both directly and indirectly, all over the world. I’m sure most of the people who feel its influence on their lives never expected to, just like me. Because you never expect dementia—before you experience it for yourself it is just a kind of faraway thing that is sad and big and scary if you think about it for too long, and something that occasionally happens on TV soaps when old people need to be written out. Nobody expects dementia, because we think we know our loved ones too well; we think their traits are too indelible, their personalities too strong, to ever be wiped out by mere disease. When it does arrive, it is unannounced; it creeps in silently and straps itself in for the long haul.

Ironically, though, however unexpected it may be when dementia comes knocking, you immediately know exactly what to expect. The distance at which you held the disease in your mind narrows very quickly, and what begins as terror and grave uncertainty becomes resignation and pragmatism. You learn to deal with the illness because you love the person it’s stealing away, and you eventually accept the fact that it’s never going to get better. Somehow, you cope. You just get used to it.

Complete Article HERE!