Seems like forever

Meditation — RECONSTRUCTING THE CHANGING FACE OF DEATH

RECONSTRUCTING THE CHANGING FACE OF DEATH

— Charles Corr

A large number of people are filled with great anxiety or discomfort at the mere mention of the term death. And yet death is, after all, one of the few common denominators that we all share.

Others report that they do not know what to think or feel about death, and that this perplexity makes them unsure about taking part in inquiries related to death.

Others report that they do not know what to think or feel about death, and that this perplexity makes them unsure about taking part in inquiries related to death.

Exceptions to these prohibitions against the study of death are sometimes granted to theologians or philosophers on the ground that their work focuses on the spiritual dimensions of death.

These conflicting viewpoints remind us of the limitations of our own experience and draw attention to the important role our own attitudes and personal concerns play in determining whether and how we will deal with projects concerning death.

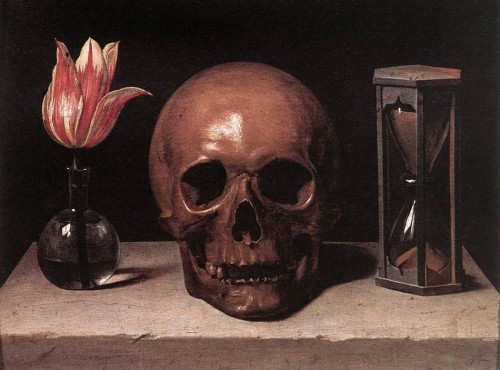

Death is not a single, monolithic entity; it is a complex and many sided dimension of human experience.

I think it is helpful to start out, not with large-scale philosophical or religious theories of the ultimate meaning of death, but with a more proximate and prosaic examination of those experiences and attitudes that are related to death and encountered in our daily lives.

Death is present in the cycles of growth and decay that we witness in nature, in the pets and other animals we bury as children, in the cemeteries and funeral homes that we drive past, and in numerous aspects of our daily experience. Yet we lack a direct contact with natural human death. We are the first “death-free” society.”

People in our society are increasingly likely to be born, grow to maturity, have children of their own without ever witnessing the natural death of a close relative or friend. This situation is unique in contrast with the experiences of other peoples and or other times in the history of our country.

One more point to acknowledge explicitly is that the face of death, as we perceive it, is composed both of cognitive and affective elements.

Hump Day Humor – 7/18/12

Advance Directives are the beginning of care, not the end

Jerome Groopman, MD, FACP, and Pamela Hartzband, MD, FACP

One of the most difficult decisions that patients, families and physicians face involves end-of-life care. The advance directive or “living will” has become an accepted framework for patients to delineate their own preferences about what treatment they would or would not want when faced with a life-threatening disorder. But it was not always this way.

In the past, physicians and families often shielded those with potentially fatal illnesses from candid conversations about dying. The doctor or a family member would make decisions to sustain or stop treatment, typically without consulting the patient. This has changed over the past three decades following a landmark report entitled “Deciding to Forgo Life-Sustaining Treatment” issued by a presidential commission in 1983.

In the past, physicians and families often shielded those with potentially fatal illnesses from candid conversations about dying. The doctor or a family member would make decisions to sustain or stop treatment, typically without consulting the patient. This has changed over the past three decades following a landmark report entitled “Deciding to Forgo Life-Sustaining Treatment” issued by a presidential commission in 1983.

Advance directives have become increasingly used to guide patients and family members. The underlying assumption is that a great deal of the stress and complexities of making decisions about therapy will be solved if the patient specifies his or her preferences in advance. But considerable research has highlighted that choices about treatment frequently change, and advance directives often fail to accurately forecast what a patient will want when actually experiencing a severe illness.

Consider the case of a 64-year-old woman diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma. The cancer could not be fully resected. When she was informed of the extent of the tumor and the poor prognosis, she told her family that she was ready to die. “I’ve had a great life,” she affirmed. But her family prevailed upon her to undergo chemotherapy, and for eight years, the tumor was quiescent.

This woman had planned every detail of her funeral and had an advance directive that specified that should the cancer grow and her condition deteriorate, she did not want “heroic measures.” Her daughter recounted that her mother had said that “She was ready to die when her time came and that she wanted to die at home with dignity.”

After eight years of good health, the patient developed multiple hepatic metastases and liver abscesses. She required percutaneous drainage and hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics, and the metastatic lesions progressed. She became severely fatigued, spending the entirety of her day in bed. An avid reader all her life, she could hardly read more than a few pages before drifting off to sleep. Her condition continued to deteriorate.

Yet when asked, the patient insisted, “I want to keep trying. I want to fight.” The patient’s daughter told us that the family was “shocked and confused” by these sentiments. They all expected that she would reiterate her earlier wishes and forgo further treatment. Instead, the patient became determined to try other therapies. This was not due to medication or confusion; she was lucid when expressing her desire to undergo as much treatment as necessary to keep her alive.

This change in preferences around end-of-life care is not unusual. A study led by Terri Fried, MD, of Yale University, an expert in end-of-life decision making, illustrated how preferences can change. One hundred eighty-nine patients were studied over a two-year period; these patients had diagnoses typically seen at the end of life, including congestive heart failure, cancer and chronic obstructive lung disease. Although many of the patients had been hospitalized in the previous year, including some in the intensive care unit, most rated their current quality of life as good.

The study involved repeated patient interviews about their wishes to undergo specific medical interventions, such as intubation and a ventilator, and their choices about undergoing treatment that would prevent death but might, or might not, leave them bedridden or with significant cognitive limitations.

The researchers found that nearly half of the patients were inconsistent in their wishes about such treatments. Although more people whose health deteriorated over the two-year study period showed such shifts in preferences, even those whose health was stable changed their minds. Having an advance directive had no effect on whether a patient maintained or shifted his or her initial preferences about therapies.

This is one of several studies that led researchers like Dr. Fried and her colleague, Rebecca Sudore, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco to conclude that advance directives “frequently do not … improve clinician and surrogate knowledge of patient preferences.”

Muriel Gillick, MD, a geriatrician at Harvard Medical School and a researcher in end-of-life care, similarly wrote that, “Despite the prodigious effort devoted to designing, legislating, and studying of advance directives, the consensus of medical ethicists, researchers in health care services, and palliative care physicians is that the directives have been a resounding failure.”

Why do patients often deviate from their advance directives? They do so because they cannot accurately imagine what they will want and how much they can endure in a condition they have not experienced.

Our patient with cholangiocarcinoma originally set out her wishes in her advance directive, believing that life would not be worth living if she were bedridden. When she became ill, her family, being healthy, viewed her quality of life as so poor that it did not seem worth pursuing continued treatments. But the patient found that she could still take great pleasure in even minor aspects of living, enjoying the love and attention of her family.

Cognitive scientists use the term “focalism” to refer to a narrow focus on what will change in one’s life while ignoring how much will stay the same and still can be enjoyed. Another insight from cognitive psychology that is relevant to the changes in preferences for many patients is “buffering.” People generally fail to recognize the degree to which their capacity to cope will buffer them from emotional suffering. The often unconscious processes of denial, rationalization, humor, intellectualization and compartmentalization are all coping mechanisms that patients employ to make their lives endurable, indeed, even fulfilling, when ill.

Another limitation of an advance directive is that it cannot encompass every possible clinical scenario that may arise. For example, a patient is newly diagnosed with an incurable lung cancer with a life expectancy of two years or more. The patient states in his advance directive that he does not wish to be placed on a ventilator. Soon after initiation of treatment, the patient develops pneumonia, and intubation with ventilation for a few days is needed for support as the antibiotic therapy takes effect. Should this patient forgo being placed on a ventilator?

Over the past two decades, there have been attempts to refine the advance directive by having the patient specify at the time of hospital admission the types of treatments that are acceptable: full CPR or not, intravenous fluids, comfort measures like oxygen and pain medications. Physicians then write orders in the patient chart about each of these interventions.

While this refinement may be helpful, researchers in end-of-life care emphasize that there are no shortcuts around emotionally charged and time-consuming conversations that involve patients, families and physicians.

Even with detailed initial instructions, patients may change their minds. Repeated communication can help bring clarity to these difficult decisions. We believe an advance directive is an important beginning, but not the end, of understanding a patient’s wishes when confronting severe illness.

Complete Article HERE!

Talking with teens about death

Study finds that seriously ill young people want to discuss their care, wishes — Barbara Brotman

It is the hardest conversation a parent can imagine: talking to a critically ill child about the possibility of death.

But Deb Fuller, of Woodstock, wishes she had done it sooner.

By the time she and her husband broached the subject with their nearly 13-year-old daughter, Hope, her brain cancer was so advanced that she could barely speak.

By the time she and her husband broached the subject with their nearly 13-year-old daughter, Hope, her brain cancer was so advanced that she could barely speak.

Fuller asked Hope if she was afraid; if she was worried about how her parents and brother would cope when she was gone; if she was ready to go anyway.

Hope answered by squeezing her mother’s hand: Yes. Yes. And yes.

“That ended up being one of the best nights we had,” Fuller said. “We all sat around together to the wee hours of the morning and talked.

“But I waited too long. I thought we had more time,” she said.

Hope died within days.

“I wish she could have spoken to me,” she said. “I hate the thought that perhaps she laid there … and worried about it, unable to talk to me about it.”

End-of-life experts say that children should have the opportunity to discuss death in a developmentally appropriate way with a parent or a knowledgeable adult, though such conversations should not be forced.

And a recent study shows that many seriously ill children want to have that talk, and that both they and their parents are relieved afterward.

But parents often don’t know how to begin an end-of-life conversation with their children, said Maureen Lyon, associate research professor in pediatrics at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington and principal investigator at its Children’s Research Institute.

They are often afraid that talking about death will be harmful to the child, Lyon said. And by the time teenagers enter hospice or palliative care programs, which are adept at such conversations, the youths may be too ill to be able to talk or not want to at all.

But it can be a crucial conversation, Lyon said. Important decisions may have to be made, like whether to discontinue aggressive medical treatment or whether they would want to die at home or in a hospital.

Too often, no one — not even doctors — asks these questions of seriously ill teenagers themselves, she said. Without knowing their children’s wishes, families can be torn apart by conflict. And though youths under 18 have no legal standing to direct their medical care, Lyon said, their opinions should be heard.

She and Linda Briggs, associate director of the Respecting Choices program at Gunderson Health System in La Crosse, Wis., designed a way they can be.

They conducted a study in which they used facilitators to guide seriously ill young people and their families through conversations about end-of-life care — the same kind of conversations Respecting Choices offers to adults. At the end, the teens filled out advance directives outlining their wishes.

The study, which Lyon and Briggs presented at the annual conference of the International Society of Advance Care Planning and End of Life Care held recently in Rosemont, found that the youths wanted to be consulted, parents wanted to know their children’s thoughts and both teenagers and their families found the experience worthwhile.

Moreover, the conversations did not cause harm. The young people — who were between 14 and 21 and had either HIV or cancer — were no more anxious and depressed after they talked.

“The assumption is that these conversations will take away hope and raise anxiety. The reality is the opposite,” Briggs said.

Not that the conversations were entirely pain-free.

“The study was much harder on the teens with cancer,” Lyon said. A small percentage of those youths said they had found the talks hurtful. However, they also found them worthwhile. Lyon hypothesized that because they were more ill than the HIV-positive youths, the possibility of death was more real.

But Jessica Gaines, 22, who participated in the study as an 18-year-old who had been treated for Hodgkin lymphoma, said she was glad to be finally asked her opinion.

“When I was going through treatment, I was never asked, ‘Well, what happens if you don’t make it through?'” said Gaines, who lives outside Washington.

Parents were appreciative of the talks too. “I feel like a load was lifted,” one commented in a survey.

Some teens and families declined to participate. Hospices, too, find that not everyone wants to have such talks.

Jeremy Campus, 13, of the Northwest Side, is battling cancer that has recurred a third time. A patient at Hospice and Palliative Care of Northeastern Illinois, Jeremy is well aware of the gravity of his condition. His mother, Annmarie, has let him know that she is available to talk about anything, and his palliative care team is similarly open.

But when it comes to addressing the worst possibility, the quiet-voiced boy sitting at his family’s dining room table is clear.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” he said.

Some parents don’t want their children to talk about it.

“I was against, until the last breath of my son, for anybody to even to mention the word death to him,” said Alla Lyubyezny, of Buffalo Grove, whose son, Max Stine, died of brain cancer five years ago. He was 17 and a patient at Horizon Hospice and Palliative Care.

She didn’t want Max to lose hope, and considered it her duty to protect him from the pain of confronting death.

“Nobody needs to have this information, and to live their last, the month of time that is left to them, with that,” she said. “There are some subjects that are best left alone.”

But children generally know how sick they are, said Jennifer Misasi, head of Horizon’s pediatric program. They sometimes avoid talking about it to protect their parents, she said.

And there is no evidence that talking about impending death in a sensitive and appropriate way takes away children’s or parents’ hope or leaves them devastated, said Dr. David Steinhorn, medical director of the palliative care program at Chicago’s Lurie Children’s Hospital.

“Parents who have the opportunity to have frank conversations in a supportive, open way actually do much better and have fewer regrets when their child is dead than parents who do not talk about it,” he said.

“We’re not saying this should be imposed on anybody,” Lyon said. “But for those teens that want to have a voice, this works.”

“This isn’t about ‘Do you want CPR, yes or no,'” Briggs said. “It’s having them express their goals and values.

“How would you want your mom to make decisions for you? What would you want your mom to know about what kind of life makes sense to you, and what kind of life doesn’t make sense to you?”

Complete Article HERE!

D.C.’s Marijuana Reform Rabbi

Jeffrey Kahn and his wife are set to open one of the first medical marijuana dispensaries in Washington, D.C.

Jeffrey Kahn, a Reform rabbi living in Washington, D.C., remembers several congregants who approached him over the years with the same dilemma: They’d heard that marijuana could relieve their nausea from chemotherapy or their pain from glaucoma or any one of a variety of other ailments, but they were unable to obtain the drug because it’s illegal.

The issue became personal when Kahn and his wife, nurse Stephanie Reifkind Kahn, watched her parents suffer and die—Jules Reifkind of multiple sclerosis in 2005 and Libby Reifkind of cancer in 2009. The Reifkinds’ doctors had recommended marijuana to ease their symptoms, but they lived in states where medical marijuana was illegal, making it nearly impossible for them to obtain the drug. Jules did use it a few times, probably getting it from a caregiver, his daughter remembers, and it reduced his pain and muscle spasms.

After the deaths of Jules and Libby Reifkind, the Kahns made it their mission to ease the suffering of others who might benefit from medical marijuana. For the past two years, they have been laying the groundwork for a legal dispensary for medical marijuana in Washington. Earlier this month, their efforts paid off: The D.C. Department of Health named four applicants eligible to register to operate such dispensaries—the first ones in the District—and the Kahns’ Takoma Wellness Center was one of them.

Dispensing marijuana may not be the usual path for a rabbi. But there is rabbinical support for the practice. And on a personal level, Kahn, 60, told me last week: “Our midlife quest for a new way to make a positive difference in people’s lives and a lifelong commitment to pushing the envelope to help others made this the obvious path to follow.”

***

College sweethearts who married 36 years ago during spring break from the University of Florida, the Kahns made aliyah in 2007. In Israel, he was involved in fundraising for Jewish organizations, after having spent more than 25 years with four different Reform congregations, including six years in Adelaide, the capital of South Australia.

But the economic downturn in 2008 made fundraising difficult, Kahn told me. Their older son, who’s also a Reform rabbi, had moved to Washington, D.C., where he now works for a Jewish social service organization. When they came for the bris of their grandson, now 3, they realized they didn’t want to live so far away from the baby. (Their younger son, who made aliyah at age 20, now serves as the Jewish Agency for Israel’s shaliach at his parents’ alma mater.) It was a homecoming of sorts for Stephanie Reifkind Kahn, who was born 57 years ago in Takoma Park, Md.—which borders the Takoma neighborhood in D.C. where they now live.

Medical marijuana was a hot-button issue in the nation’s capital when the Kahns moved here. Washington, D.C., voters had approved the legalization of medical marijuana more than 2-to-1 back in 1998, but Congress—granted ultimate authority over the city by the Constitution—blocked it with an amendment to the D.C. appropriations bill. In December 2009, though, Congress repealed the amendment, due in part to lobbying by former Georgia Republican Rep. Bob Barr, who had originally added it. The city issued regulations in July 2010 that said it would license up to five dispensaries and 10 cultivation centers; neighboring Maryland and Virginia have not yet legalized medical marijuana.

‘I think the rabbi is doing the Lord’s work’

With their sons’ blessings and, eventually, the support of their local Advisory Neighborhood Commission, the Kahns started paying rent a year and a half ago on a long-vacant, 1,300-square-foot former attorney’s office within steps of the Takoma Metro station. Their apartment is half a block away; their older son and his family, which now includes two grandsons, live two miles away.

The Kahns submitted 350 pages of documents to support their application. “We had this pretty strict review process,” said Mohammad Akhter, the physician who directs the D.C. Department of Health. “It’s very tightrope-walking. On the one hand we have a city law. On the other hand, we have law-enforcement officials, federal officials, who consider this not quite kosher.”

Applicants had to demonstrate that they “had the knowledge about what this business was all about,” Akhter said, and they needed to be able to provide adequate security and keep scrupulous records. (To avoid a conflict of interest, Akhter noted, he has never met the Kahns or any of the 16 other parties who applied to dispense medical marijuana in Washington.) “I think the rabbi is doing the Lord’s work,” said the Pakistani-born doctor, noting that Washington has high rates of diseases for which medical marijuana is approved, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer.

In August 2010, the Washington City Paper predicted that the first dispensaries might open in the spring of 2011. Akhter attributes the delay to the typically slow wheels of government and the desire to ensure that federal law-enforcement officials won’t shut down the dispensaries as soon as they open. “It’s a very lengthy process in terms of doing the review,” he said. “As a physician, I look at this as approving a new drug. We have done all the due diligence possible.”

Dispensing medical marijuana doesn’t pose any particular conflict for a rabbi, said Kahn: “As a medicine, there are no Jewish issues,” he told me. Just as sick Jews aren’t supposed to fast on Yom Kippur, he says, neither should they be expected to suffer because the federal government says marijuana has no medical benefit, especially given that 18 other Western countries that have legalized it for medical purposes—as well as 17 states plus D.C.—disagree.

The Union for Reform Judaism passed a resolution nearly nine years ago on “the medicinal use of marijuana.” “According to our tradition, a physician is obligated to heal the sick,” the resolution states. And, at least anecdotally, marijuana apparently “provides relief from symptoms, conditions, and treatment side effects of several serious illnesses.” For that reason, the resolution urges “congregations to advocate for the necessary changes in local, state, and federal law to permit the medicinal use of marijuana and ensure its accessibility for that purpose.”

It’s not just Reform rabbis, either. A number of rabbis across the spectrum of observance believe prescribing medical marijuana to relieve suffering is acceptable under Jewish law.

“Basically, Jewish teaching is extremely supportive,” said J. David Bleich, an Orthodox rabbi and professor of Talmud at Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary and head of its postgraduate institute for the study of Talmudic jurisprudence and family law. “The beneficial purpose of marijuana seems to be countering the side effects of chemotherapy and other symptoms … and there’s no reason society shouldn’t take advantage of it.” Jurisdictions that approve and regulate medical marijuana, Bleich said, “certainly are to be lauded.”

The Kahns hope they’ll be able to serve their first patients by the beginning of December. For now, though, there is no marijuana to dispense, because in Washington, the dispensers of medical marijuana won’t be the ones growing it. In addition to approving four dispensaries out of 17 applicants, the health department approved six cultivators from among 28 applicants. (One of the six is a company co-owned by former talk-show host Montel Williams, a Maryland native who uses medical marijuana to treat his multiple sclerosis.) The cultivators still need to make structural changes to their facilities and haven’t yet started growing marijuana, Akhter says; once they begin, it will take 90 to 100 days before they will be able to supply the dispensaries.

No patients have yet been approved by the health department to receive medical marijuana, either, although many have expressed an interest, Akhter says. They must prove that they live in D.C. and receive a prescription from a doctor licensed to practice in the city. This process, too, will take time.

Once they open their doors, the Kahns’ have a business plan based on serving 500 patients their first year, although at best that’s a guesstimate. Their dispensary will serve patients by appointment only, making it less like a retail store and more like a doctor’s office, Kahn says. He and his wife also plan to partner with Takoma providers and refer patients to a wide array of complementary health services available in the laid-back neighborhood.

The Kahns hope that their dispensary will serve as a model for Congress to see that marijuana can safely be used to treat appropriate patients without ending up being diverted to people who aren’t ill. Kahn summed up his mission: “There’s no reason for people to be suffering and not getting the help they need.”

Complete Article HERE!