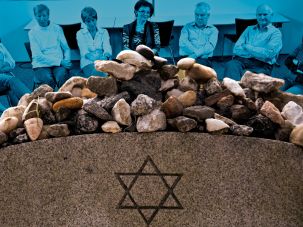

One sunny Thursday evening in June, eight people, ranging from thirty-somethings to senior citizens, sat around a table at the Manhattan Jewish Community Center nibbling on cookies.

In front of them stood Sally Kaplan, one of three facilitators present from the organization What Matters, a New York City-based not-for-profit that facilitates group and individual conversations about advanced care planning. Sally interrupted the snacking to provide the group with a directive: pair off with the person next to you and talk about when you first realized you were mortal.

In front of them stood Sally Kaplan, one of three facilitators present from the organization What Matters, a New York City-based not-for-profit that facilitates group and individual conversations about advanced care planning. Sally interrupted the snacking to provide the group with a directive: pair off with the person next to you and talk about when you first realized you were mortal.

The participants looked around at each other; a few nervously giggled. There was a moment of uncertain silence. And then, everyone turned to their partner, and a rush of words poured forth. Death, it seems, can be confronted.

The What Matters event is just one example of a surge in Jewish programming focused on end-of-life issues, from speeches to workshops to unstructured discussions reminiscent of Death Cafes, where strangers meet over coffee and cake to talk about any topic related to death they so choose. (I’ve attended and written about death cafes before, although at the earlier ones I attended, participants ate pancakes or Chinese food rather than desserts.) The first “café mortel” was held in Switzerland in 2004. Since then, the movement has spread globally: from living rooms in Cincinnati to (thwarted) plans for a permanent café in London to China, where sickness and mortality remain taboo.

And the death café now has Jewish equivalents: Over the past years, death café-esque events have been held at Jewish community centers, senior homes, synagogues, and even mortuaries. Most recently, a coalition of Westchester County, New York synagogues organized a series[ of “death cafes” (the events were more structured than the traditional café mortel) centered around subjects like Jewish funerals and the afterlife in traditional Jewish thought. In Israel, Rabbis Miriam Berkowitz and Valerie Stessin, who founded the pastoral care initiative Kashouvot, have also hosted death cafes in the past. The Dinner Party, a network of meal-based gatherings for young adults who have experienced loss, currently offers kosher dinners in New York City.

In 2016, Death Over Dinner, an American initiative similar to Death Cafe, partnered up with IKAR, a Los Angeles-based non-denominational Jewish community, and Reboot, a nonprofit Jewish think tank, to launch Death Over Dinner: Jewish Edition.

“We launched [the pilot] on Yom Kippur, because that is the quintessential Jewish moment of facing our mortality,” says Francine Hermelin, the creative director of Reboot. Though Reboot and Ikar have hosted dinners themselves, in addition to having partnered with organizations like Moishe House and the Contemporary Jewish Museum of San Francisco, they also offer an online questionnaire that helps guide a potential host to stage a dinner in his or her own home. They soon plan to add printable cards with verbal prompts, including quotes from psalms, Talmudic wisdom, and food for thought from contemporary rabbis, as an additional resource.

“[This initiative] is to make that personal shift, and ultimately a cultural shift, where talking about death is no longer a conversation we’re afraid of but a conversation that we are embracing,” Hermelin says.

The increased focus on mortality in recent years is likely the result of a combination of factors: an aging population living increasingly longer and facing unprecedented healthcare situations, a greater openness towards talking about historical taboos generally, and a growing consumer interest in wellness, including a concept of “the good death.” And Jewish initiatives focused on death and mourning want to take part in this larger dialogue, using spirituality and Jewish tradition as a foundation. Indeed, a 2017 Pew study found that “geographically and theologically diverse” faith communities were uniquely suited to address concerns around death and mourning, even for those with no prior religious affiliation.

“We [in the Jewish community] seized upon this wave,” says Kaplan, who points to books like Atal Gawande’s On Being Mortal and Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air as examples of the trend. Though What Matters is non-denominational––Kaplan describes it as “value neutral and person-centered”––Kaplan says she sees confronting mortality through discussion as a “very Jewish” enterprise, one she feels is reflected in Jewish texts. “People are surprised that there are so many Talmudic stories that deal with advanced care planning!” For further insight, Kaplan referred me to Rabbi Mychal Springer, Director of the Center for Pastoral Education at the Jewish Theological Seminary, who cites the story of Rabbi Yehudah Ha-Nassi, who was unable to die while his students were incessantly praying for him, until his handmaid dropped a jug from the roof and distracted them. In the moment of silence, Ha-Nassi was able to depart peacefully. ” This is a classic example of the way the rabbis were saying we shouldn’t prolong the dying process,” Rabbi Springer said.

Support doesn’t always come in the form of face-to-face groups: Lab/Shul, a creative Jewish community based in Lower Manhattan, operates an initiative called Kaddish Club, which includes a monthly potluck dinner in New York City, and a 15-minute weekly phone call they’ve dubbed Virtual Mourners’ Kaddish. During the calls, which began in 2014, the far-flung bereaved reflect on their departed loved ones, share some wisdom, and then recite Kaddish together.

“We’ve had folks call in from all over the country and all over the world,” says Sarah Strnad, Lab/Shul’s Director of Operations. “A lot of the traditional options [i.e. daily kaddish in a synagogue setting]… don’t always work in our modern lives.” Strnad says one of the most moving things about the calls is how they end up becoming micro-communities. “Even on the virtual calls, when people might never see each other in person, they remember each other’s stories and they can give each other support week after week.”

Of the current offerings, few are Orthodox in orientation. This might be because those who identify as Orthodox see processes around death as strictly prescribed ––decisions about life support deferred always to the ordained, mourning periods a certain length, prayers predetermined –– and therefore not necessary to hash out.

But Elad Nehorai, founder of Hevria and Forward contributor has imminent plans to hold a death café that will include a more observant audience (though he hopes to provide a space for the observant, he stresses that anyone is welcome). Nehorai, who has attended “secular” death cafes in the past, told me, “It was actually my fascination with death that caused me to choose to be Hasidic after growing up secular. Death has this fascinating power to force us to face what we really believe. Even as believers, we must face our beliefs in a brave way. Death forces us to do that.” (Full disclosure: Elad and I collaborated in organizing this event.)

During the course of my writing this piece, I attended my grandfather’s memorial service, tried to comfort a friend whose loved one was gravely ill, and heard a rabbi speak about ministering to a father grieving for his child as one of his first clerical duties.

Even though I had thought it slight hyperbole when she said it, I realized Francine Hermelin’s assertion that “we’re always experiencing death” was absolutely true. Though we may find it difficult to face our end with courage, as Nehorai hopes we can, we should do our utmost to be as prepared, emotionally, logistically, and spiritually, when the time inevitably comes, for as it says in Genesis, “For you are dust, and dust you shall return.”

Thankfully, there is increasingly more out there to help us do just that.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!