[T]hese days many people know they are dying long before death finally arrives. Yet death, a natural event, is often seen as a failure of medicine. Despite the additional time modern healthcare may provide us, we still begin our conversations about the wishes of the dying and their families too late – or not at all. This reluctance to accept our own mortality does not serve us well.

This taboo around death is a fairly modern, Western phenomenon. Past and present, societies have dealt with death and dying in diverse ways. It is clear from, for example, the outpouring of grief at Princess Diana’s death, and the conversations opening up around the 20th anniversary of the event, that these outlets are needed in our society too. High-profile celebrity deaths serve as sporadic catalysts for conversations that should be happening every day, in everyday lives.

Recent bereavement theory has moved on from thinking of grief as a series of stages, to a continuous process in which the bereaved never fully return to some “pre-bereaved” status quo. It is increasingly recognised that the living form various sorts of continuing bonds with the dead, as put forward by the sociologist Tony Walter and psychologist Dennis Klass and colleagues – and this is certainly something that can be seen in death practices today across the globe, and among those practised in the past.

In Neolithic Turkey, one funerary rite included the creation of plastered skulls – family members were buried under the floors of their house and after some time the skull was removed and a plaster face lovingly recreated over it. Many of these plastered skulls show evidence of wear and tear, breakage and repair, suggesting that they were used in everyday life, perhaps displayed and passed around among the living. Similarly, in modern-day Indonesia, the dead are kept in houses, fed and brought gifts for many years after death. While in this state they are considered to be ill or asleep – in this case their biological death does not entail social death.

It was not so long ago in the UK that public outpouring of grief and practices that kept the dead close were acceptable. For example, in Victorian England, mourning clothes and jewellery were commonplace – Queen Victoria wore black for decades in mourning for Prince Albert – while keeping tokens such as locks of hair of a deceased loved one were popular.

However, today death has been outsourced to professionals and, for the most part, dying happens in hospitals or hospices. But many doctors and nurses themselves feel uncomfortable with broaching the subject with relatives. Perhaps there are lessons to be drawn from the attitudes of others far removed from us in time and space: the past, and societies on the other side of the globe, are easier to discuss, yet act as prompts to help us discuss more personal experiences.

The Continuing Bonds Project brings together healthcare practitioners and archaeologists at the University of Bradford and LOROS Hospice in Leicester to explore what we can learn from the past, using archaeology to challenge modern perceptions of and attitudes towards death and dying, and as a vehicle through which people can discuss their own mortality and end-of-life care.

Remember, remember

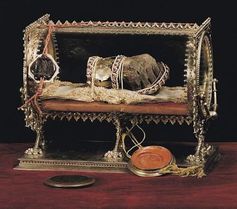

One case study we show our workshop participants is the Holy Right Hand of St Stephen, a relic of the first king of

Hungary which has been on display since 1038. Though saints’ relics – generally body parts – have been a large part of Christian culture in the past and were not uncommon, they are something many are uncomfortable with today. One workshop participant describes the display of St Stephen’s hand as “selfish”, as if he is being exploited beyond the grave. What responsibilities do we have towards the dead? What constitutes “respect” for them? Archaeology shows us that it is a fluid and culturally embedded concept which differs wildly between societies and individuals.

Memorialisation, through photographs or statues (that served the same purpose in the past), appears to be fundamental to “respectful” treatment of the dead. Death masks – plaster castings of a dead person’s face – and later even photos of the recently departed, were not uncommon as a way to memorialise the dead, even into the 20th century. Yet while taking photographs of the departed in life are celebrated, photographs of dead bodies themselves are less palatable today.

Another example for workshop participants is the statue of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II, the bust of which

resides at the British Museum, while the feet remain in situ at the Ramesseum in Luxor, Egypt. Given that this individual lived in Egypt nearly 3,000 years ago, the statue has kept his memory alive. Yet its fragmented and dispersed nature prompted our participants to wonder how long their loved ones’ memories of them would persist after their death, and what legacies they would want to leave.

101 uses for mortal remains

Memorialisation of the dead takes a very different form at the 16th-century Capela dos Ossos in Évora, Portugal, where monks desiring to save the souls of some 5,000 people from overcrowded local cemeteries used their remains to create a chapel of bones. Individual bones were used to create decorative features such as arches and vaulted ceilings.

Workshop participants were unhappy that bones had been removed from their resting place without the permission of the deceased. But for how long can our wishes be accommodated after death? The other feature that unsettled them was the dismantling of the skeletons – in the West today, our identity sits firmly with us as individuals, bounded by our physical bodies. Fragmenting our skeletal remains strikes firmly at this sense of identity – and so our sense of social presence. Such scattered remains are nameless, faceless – lacking the very thing that memorials seek to preserve.

In other cultures – and in the past – identity is less individualistic and resonates within larger kin or community groups. Here, distributing bones may be less problematic and a part of the process whereby the recently deceased joins the host of communal ancestors.

‘Nice chapel, I love what you’ve done with the space.’

Though some of the topics were difficult to discuss, many workshop participants felt they had improved confidence in talking about death, dying and bereavement as a result. The range of practices from the past reminds us of the diverse ways through which death can be negotiated and the extent to which practices that we take for granted today are in fact culturally embedded, relative and subject to change. Persistent Facebook profiles of dead friends and family to which loved ones post on each anniversary are an example of how traditions are changing.

In a world where death has become increasingly outsourced and medicalised, the diverse ways we treated and remembered our dead in the past should highlight the choices available to us and prompt us to consider those now banned or taboo. At the entrance of the Capela dos Ossos, the monks who built the chapel left an inscription, a momento mori that reminds us: “We bones that are here, for yours await”.

Complete Article HERE!