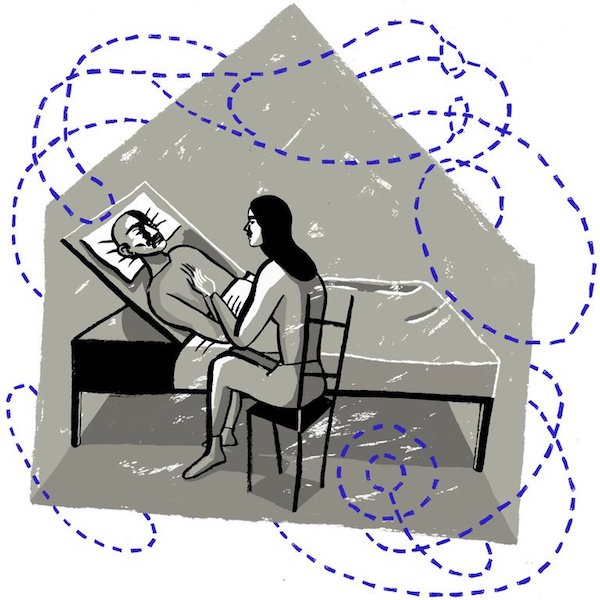

[W]hen my father was dying of pancreatic cancer last summer, I often curled up with him in the adjustable hospital bed set up in his bedroom. As we watched episodes of “The Great British Baking Show,” I’d think about all the things I couldn’t promise him.

I couldn’t promise that the book he’d been working on would ever be published. I couldn’t promise he would get to see his childhood friends from England one more time. I couldn’t even promise he’d find out who won the baking show that season.

But what I could promise — or I thought I could — was that he would not be in pain at the end of his life.

That’s because after hearing for years about the unnecessary medicalization of most hospital deaths, I had called an in-home hospice agency to usher him “off this mortal coil,” as my literary father still liked to say at 83.

When a doctor said my father had about six months to live, I invited a hospice representative to my parents’ kitchen table. She went over their Medicare-funded services, including weekly check-ins from a nurse and 24/7 emergency oversight by a doctor. Most comfortingly, she told us if a final “crisis” came, such as severe pain or agitation, a registered nurse would stay in his room around the clock to treat him.

For several months, things went well. His primary nurse, who doubled as case worker, was kind and empathetic. A caretaker came three mornings a week to wash him and make breakfast. A physician assistant prescribed drugs for pain and constipation. His pain was not terrible, so a low dose of oxycodone — the only painkiller they gave us — seemed to suffice.

In those last precious weeks at home, we had tender conversations, looked over photographs from his childhood, talked about his grandchildren’s future.

But at the very end, confronted by a sudden deterioration in my father’s condition, hospice did not fulfill its promise to my family — not for lack of good intentions but for lack of staff and foresight.

At 7 p.m. on the night before my father’s last day of life, his abdominal pain spiked. Since his nurse turned off her phone at 5, I called the hospice switchboard. To my surprise, no doctor was available, and it took the receptionist an hour to reach a nurse by phone. She told us we should double his dose of oxycodone, but that made no difference. We needed a house call.

The only on-call nurse was helping another family two hours away. So my sister and I experimented with Ativan and more oxycodone, then fumbled through administering a dose of morphine that my mother found in a cabinet, left over from a past hospital visit. That was lucky, because when the nurse arrived at midnight, she brought no painkillers.

After the nurse left, my father’s pain broke through the morphine. I called the switchboard again, and it took three hours for a new nurse to come. She was surprised he hadn’t been set up with a pump for a more effective painkiller. She agreed that this constituted a crisis and should trigger the promised round-the-clock care. She made a phone call and told us the crisis nurse would arrive by 8 a.m.

The nurse did not come at 8 a.m. Or 9 a.m. When his case worker was back on duty, she told us — apologetically — that the nurse on that shift had come down with strep throat. Her supervisor stopped by, showed us the proper way to deliver morphine (we’d been doing it wrong) and told us a pain pump and a crisis nurse should arrive by noon.

Noon passed, then 1 p.m., 2 p.m. No nurse, no pump.

By this time, my father had slipped into a coma without our noticing; we were thankful his pain was over but heartbroken he wouldn’t hear our goodbyes. Finally, at 4 p.m., the nurse arrived — a kind, energetic woman from Poland. But there was little left to do. My father died an hour later.

At the end of life, things can fall apart quickly, and neither medical specialist nor hospice worker can guarantee a painless exit. But we were told a palliative expert would be at my father’s bedside if he needed it. We were not told this was conditional on staffing levels.

I didn’t realize how common our experience was until a few months after his death, when two reports on home hospice came out — one from Politico and one from Kaiser Health News. According to their investigations, the hospice system, which began idealistically in the 1970s, is stretched thin and falling short of its original mission.

Many of the more than 4,000 Medicare-certified hospice agencies in the United States exist within larger health care or corporate systems, which are often under pressure to keep profit margins up.

Kaiser Health News discovered there had been 3,200 complaints against hospice agencies across the country in the past five years. Few led to any recourse. In a Medicare-sponsored survey, fewer than 80 percent of people reported “getting timely care” from hospice providers, and only 75 percent reported “getting help for symptoms.”

I called Edo Banach, the president of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, to get the trade group’s response. He expressed sympathy for my father’s suffering but was adamant that good hospice experiences “far outweigh” the negative ones.

Granted, more than a million Medicare patients go into hospice care every year, so the complaints are in the minority. Mr. Banach told me he’s worried that drawing attention to what he called the “salacious” stories of failed hospice care means more families will turn to less holistic, less humane end-of-life care. That could be true. But then, should there be more transparency early on? Should the hospice reps explain that in most cases, someone will rush to your loved one’s side in a crisis, but sometimes the agency just doesn’t get the timing and the logistics right?

As the number of for-profit hospice providers grows, does that model provide too great an incentive to understaff nighttime and weekend shifts? The solution may have to come from consumer advocacy and better regulation from Medicare itself.

A new government-sponsored website called Hospice Compare will soon include ratings of different agencies, which will ideally inspire some to raise their game. When I looked up the agency we had used, its customer satisfaction rate for handling pain — based on the company’s self-assessment — was 56 percent.

I considered making a complaint in the days after my dad’s death, but frankly we were just too sad. Even now, I believe hospice is a better option than a sterile hospital death under the impersonal watch of shift nurses we’d only just met. But I wonder whether that hospital oversight might have eased my father’s pain earlier on that last day.

Ultimately, even without pain relief, he was probably more comfortable in his own home, tended by his children, doing our best.

But then I think: He deserved to have both.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!