The ‘grief police’ wield lamentable shaming tactics.

By Sian Beilock

When Kobe Bryant died on Jan. 26, there was an outpouring of grief for the legendary N.B.A. champion. Sports fans placed bouquets of flowers at his high school and held a vigil outside the Staples Center. Shaquille O’Neal, his friend, rival and former Lakers teammate, cried on TV while giving an emotional tribute.

Much of this grieving also took place on social media. His widow, Vanessa Bryant, wrote a powerful tribute on Instagram that was “liked” by more than nine million people. So did Carmelo Anthony and Chris Paul. Grief is no longer private these days, which lets us mourn together. But doing so also allows people to publicly shame how others deal with loss.

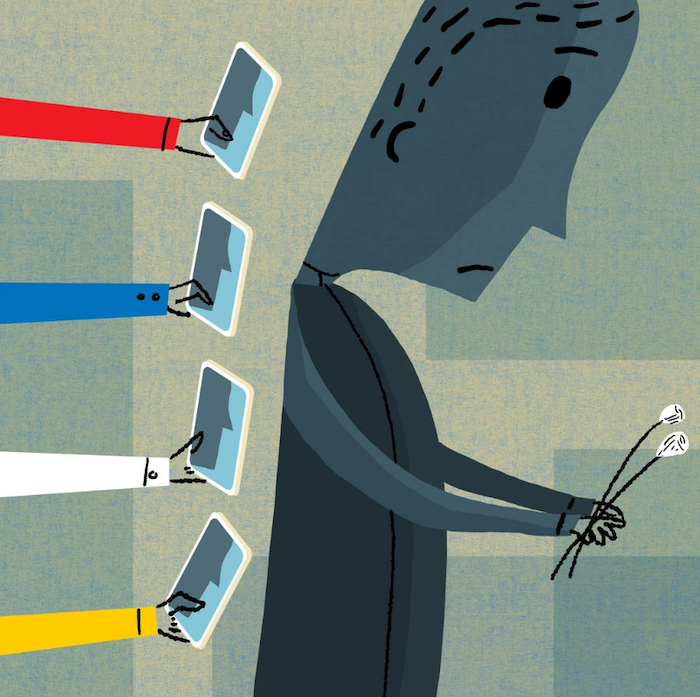

“Cancel the games. Cancel the Grammys.,” one person wrote on Twitter. Another criticized those who brought up the rape allegation against Bryant in their commemorations: “Some people have no respect for the dead.” This is part of a broader phenomenon. These “grief police” enforce murky standards of who should be sad, when they’re allowed to be and to what degree. They insist that our grief must be overwhelming and ubiquitous, and for all parts of our lives to be put on hold. This isn’t just problematic in the moment; introducing guilt into the grieving process can negatively impact others’ ability to heal.

Something similar happened at Barnard College where, in December, we were forced to grieve in the media spotlight after one of the newest members of our community, the first-year student Tess Majors, was murdered. I have spent my career researching anxiety and worry, and I was struck by a commonality among people on campus: Amid their feelings of heartbreak, members of our community were worried about how others would perceive their specific form of grieving.

I wasn’t aware of students policing others’ grief, but the perception that this was happening still had an effect, especially given the media attention around the tragedy. One student told me that, in the midst of her deep sorrow, she also felt guilty about feeling eager to write her final papers and was worried she would be judged for not mourning in the “right” way. Another student mentioned that she didn’t know Tess Majors personally and was feeling all right, even looking forward to a long-planned family trip over break, but was going to keep this thought to herself.

I bet some of the N.B.A. players who were eager to play in the wake of Bryant’s death also had mixed feelings — because they are being judged. LeBron James was skewered online for not immediately posting about his friend and mentor: “Why are you not posting Kobe? I never liked LeBron because he is always FULL of himself,” one person wrote on social media.

Public grieving doesn’t happen in a single community where there are shared social norms for how to react, like sitting shiva or walking in a second line. If bereaved players are slow to comment publicly, should we call them out? Must everyone who has ever met Bryant say something in public? When people with vastly different lived experiences come together around a public death, there is no real shared understanding of what is appropriate; this is why the grief police wield such power in calling people out.

Unfortunately, introducing blame into the grieving process causes people to question whether they are dealing with loss the right way and to feel guilty about what they do, say and feel. Recent research has linked guilt in bereavement to a wide range of mental and physical difficulties, including depression. So how, in the age of communal and public mourning, do we grieve and not let the grief police undercut how we feel? How do we continue to perform at our best with heavy hearts?

Everyone responds to death differently, and it’s psychologically healthy to focus on parts of our identity that are not touched by tragedy. It is O.K. for a grieving athlete to play an important game; the same goes for a student who wants to take her finals in the wake of a campus tragedy. Research on resiliency shows quite clearly that people who express (and value) different aspects of who they are tend to be psychologically stronger. For example, their role as an athlete, student or parent provides another outlet to express themselves if they experience a setback or loss in one aspect of their life, or if one of the ways they identify themselves is called into doubt.

Embracing the fullness of our identities in no way represents a lack of respect or a blindness to the gravity of a tragedy. Quite the opposite: It is only through this process that we can effectively take care of one another, including those who have been most affected.

Despite my expertise in this subject, I have had to force myself over the last month to realize that, even in mourning, I have to juggle life as a college president, a researcher, a mother, an athlete and a friend — not only for my own health and mind-set, but also for the well-being of those around me. When the grief police arrive, we need to give ourselves license to express positive emotions and affirm other aspects of ourselves that we value outside of the tragedy. Doing so means we will feel more in control and cope better down the line.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!