Everyone should have the right to high-quality palliative care when they have a terminal illness, regardless of their condition, where they live, or their personal circumstances. It’s commonly assumed that everyone with a terminal illness gets the care they need, however one in four people who need palliative care in Northern Ireland are not currently accessing it.

by Craig Harrison

Raising awareness of the issues

The problem can be particularly acute within the LGBT community, and last year, research commissioned by Marie Curie found that concerns around discrimination, stigma and invisibility can often cause LGBT people to access services late or not at all.

To explore these crucial issues, Marie Curie Northern Ireland held a policy seminar to raise awareness of the barriers faced by our LGBT community in accessing end of life care and what can be done to address them.

Held in Stormont, the home of the Northern Ireland Assembly, the event brought together a wide range of stakeholder groups, departmental officials, MLAs and health and social care representatives.

Championing compassion and understanding

Guests heard from Joan McEwan, Head of Policy and Public Affairs at Marie Curie Northern Ireland, as well as John O’Doherty, Director of local LGBT organisation the Rainbow Project . John discussed the needs of older LGBT people in health and social care, and said:

“Accessing care as an older person is something many of us do not consider we will need until it is upon us – particularly end of life care. This is a difficult time for everyone, but for many LGBT people, fears of homophobia and invisibility exacerbate an already distressing and difficult time.

“Ensuring services are accessible, safe and considerate of the specific needs of LGBT people means understanding their experiences, particularly the impact of homophobia, transphobia and marginalisation throughout their life.

“Marie Curie’s work in end of life care for LGBT people is imperative to ensuring that everyone living with terminal illness in our society can access care and support that is underpinned by compassion and understanding.”

“The assumption that we were not a couple”

Guests also heard from Dr Richard O’Leary, a retired university lecturer who was a full-time carer for his late partner Mervyn. Richard said:

“When we came to access end of life care as a same sex couple we were fearful of what we might encounter from service providers.

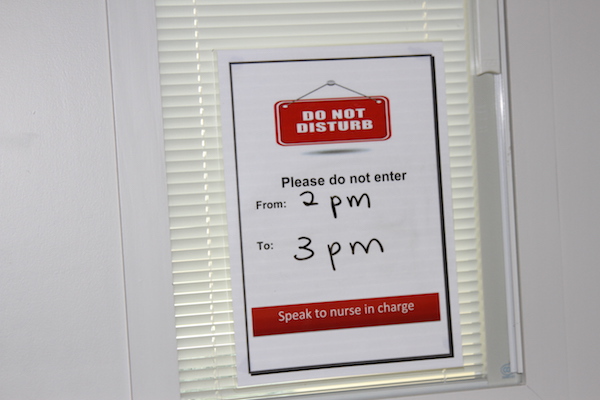

“My civil partner Mervyn was admitted to hospital many times and the assumption that we were not a couple was made at least once during every hospital stay. In the public ward in hospitals I was wary of showing affection to Mervyn because it was unclear whether the hospitals had a protocol to protect us if anyone objected to us being affectionate.

“In hospitals and hospices much of the emotional care of the dying is offloaded to the chaplaincy service. This can be problematic – with one chaplain telling me that they were ‘struggling with the issue’ of same sex relationships.

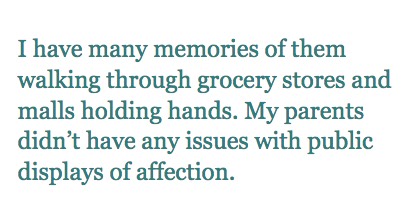

“Mervyn and I enjoyed 25 years of a committed, loving relationship until he died on 2 August 2013. After Mervyn’s death, there were people in my family and in my faith community who explicitly withheld from me the expression of condolence.

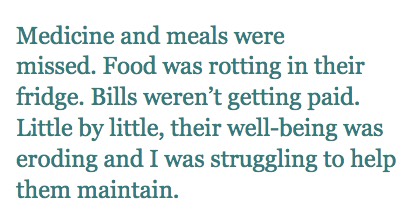

“Service providers should be aware of the disenfranchised grief and reduced social support that may be experienced by LGBT persons during bereavement. I’d like to thank Marie Curie for their pioneering research and leadership in the area of end of life care for LGBT people.”

Making good practice more widespread

The presentations made clear that there are pockets of good practice in end of life care provision for the LGBT community. Service providers and HSC professionals must now work together to take these examples and make them universal – to ensure LGBT people receive high-quality, person-centred care that acknowledges and supports them during terminal illness.

Read our report, ‘Hiding who I am: end of life care for LGBT people’ , which explores why LBGT people experience significant barriers to getting palliative care when they need it.

Complete Article HERE!