By

[O]n a recent night, I watched a man with terminal cancer die in the intensive care unit.

He was intubated. Meds ran through intravenous catheters in his bruised arms. Outside his room, alarms beeped. On the face of it, this death was precisely the kind we are told to avoid. But I think that for him, the I.C.U. was actually a good place to be.

My patient had thought he was healthy until a few months before, when the cough that wouldn’t go away turned out to be cancer in his lungs. Chemo slowed it down, but there would be no cure, his doctors told him. He was 75, and the cancer had spread to his lymph nodes and bones.

But he was living at home, eating the foods he liked, chatting with his wife. He went along that way until one day he spiked a fever and his cough worsened. The doctors in the emergency room sent him up to the I.C.U. And there we were, standing around the bed, as his breath grew ragged, wondering whether we could make him better.

Maybe with a few days of antibiotics, we could get him back home. Maybe. If we were to push ahead, with the hope that he would improve, he would need to be intubated. I turned to his wife.

She knew that he didn’t want to linger in a machine-enabled purgatory. But he would choose to undergo our interventions if there was a chance he could get well enough to return home, to be with her and the family, for whatever time he had remaining. We would take the chance.

I called the anesthesiologists. My patient’s wife held his hand as they sedated and paralyzed him so that they could place a breathing tube down his throat.

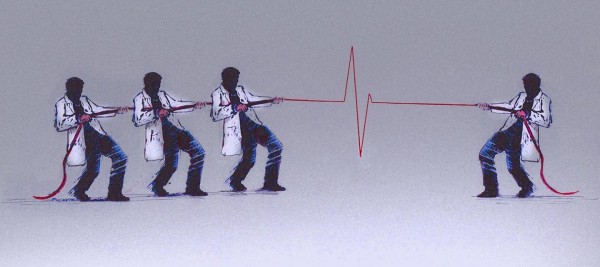

And with that, a man with a terminal illness ended up in the I.C.U., intubated, maybe dying. We know the numbers. More than 80 percent of people say they would prefer to die at home, and yet more than half of them die here in the hospital, surrounded by noise and strange smells and tubes and machines.

It’s a message that I continue to hear: Dying in an I.C.U. is a bad death that occurs when communication and understanding break down, while dying at home is a success. There is some truth to this. I have seen many men and women, bald and withered and suffering, tethered to machines that serve only to prolong an end that is inevitable.

But to cast an I.C.U. death as the negative outcome of poor communication and decision-making is too simple. Intensive care at the end of life is very often fluid, our treatments and decisions nuanced. Consider another patient, a frail man in his 80s, also with lung cancer, whose oncologist had told him he had maybe a month, at most. As his breathing grew more labored, he ended up in the I.C.U. We could not cure him — his doctors knew that, and he did, too. But perhaps we could help. We supported his breathing with high levels of oxygen, while we drained the fluid around his lung and gave him intravenous diuretics. We subjected him to the stress of the I.C.U. and a procedure, yes, but his breathing improved, not enough for him to go home again, but enough for him to be able to return to the general medical floor of the hospital. Some might argue that his story exemplifies what is wrong with our system, an example of an invasive, resource-intensive intervention in the last few weeks of life. And yet, seeing him sitting up in bed and able to take a deep breath, I considered his treatment a success — even if it bought him only days.

A procedure or an I.C.U. stay at the end of life can be a gamble. There are times when it ends the way we hope, with a treated infection, a return home. But there are times when it does not, and often, we do not know what is possible from the start. So we explain this uncertainty, and we continue to evaluate new treatment decisions with patients and their families in the context of their goals. And when the burden of disease grows too great, with further interventions more likely to cause harm than benefit, our focus can shift toward comfort. Navigating that shift is part of our training, too.

There my 75-year-old patient lay, intubated in the I.C.U. At first, the antibiotics seemed to be working, and he seemed to be getting a little bit better. We told his wife this, and she looked hopeful. But a few days passed, and then a week. He could not breathe without the ventilator. In a small conference room off the I.C.U., we told his wife that we were sorry. We had treated the pneumonia but because of the cancer, her husband’s lungs were too weak to recover. He was not going to get home. But we could maintain his dignity here, in the I.C.U., as he died. We promised her.

That night, we shut off the monitors inside his room. The screens went dark. My patient’s nurse increased the dose of his morphine drip. The respiratory therapist stepped in and removed the breathing tube. My patient breathed quickly for a moment, a little gasp, and then the morphine hit him and his breaths quieted.

We brought in his wife and two children, who gathered by the bedside. We slid shut the glass doors. From outside the room, I watched them stand there. I watched the monitors that remained on outside the room, holding my own breath as my patient’s heart rate slowed, then stilled completely. Inside his room it was quiet. There were no alarms. Through the curtains, I saw the shadow of my patient’s wife as she hunched over and began to cry, and her daughter leaned over to hold her.

And that was it. A man with metastatic cancer had died in the I.C.U.

Complete Article HERE!