How Horror Movies Prepare Us to Talk About Death

“Most things will be okay eventually, but not everything will be. Sometimes you’ll put up a good fight and lose. Sometimes you’ll hold on really hard and realize there is no choice but to let go. Acceptance is a small, quiet room.”

–Cheryl Strayed

“That it will never come again makes life so sweet.”–Emily Dickinson

There are a lot of uncertainties in life, but the only constant and known fact is that we all die. Despite this collective, inevitable experience that will eventually happen to everyone on the planet, we tend to avoid this fact altogether. It’s a painful topic, death. A fickle, unfair shadow that situates itself deep in the recesses of our minds; and when brought to the forefront, it usually initiates debilitating emotions and forces actions that the majority of us are not prepared to deal with. Our affairs are not in order; our options for burials are limited and at the mercy of a funeral director; and we are forced to make finite decisions while experiencing agonizing grief. Despite our culture’s adoration for Halloween and horror films, death is still a subject that many prefer to view as an abstract concept. It’s cathartic and safe to embrace the grim reaper within a holiday or cinematic context, but when it comes to our own mortality we recoil at the thought.

Over the past few years, thoughts about burial practices, death preparation, and the acceptance of the horror genre have been progressively evolving. 2018 was the first time that more Americans decided to choose cremation over more expensive burials. Alternative death options are becoming more widely accepted and advanced to not only alleviate the pain for loved ones, but to help reduce damage to the planet while nourishing the growth of new life through one’s passing. Additionally, the horror genre is thriving. Jordan Peele’s Get Out won an Oscar for best original screenplay in 2018; there are continuous remakes of classic genre films like IT and Pet Sematary; and numerous children’s films that lean into the spooky fascination with death such as Goosebumps and most recently Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark are all becoming more mainstream.

In his book Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, author Alvin Schwartz wrote “don’t you ever laugh as the hearse goes by, for you may be the next to die”, a line that is part of “The Hearse Song”. His trilogy of terror aimed at children was filled with creepy folklore tales and grim illustrations courtesy of artist Stephen Gammell. Straight-forward and blunt, Schwartz was revolutionary in his approach to conveying curiosities revolving around death for those at a young age. Through lore that spanned cultures across the world, he was able to shine light on a dark subject that many parents censor their children from entirely. However, this type of censorship ultimately does not help children. Just like Disney fairytales of a happy ending where the good guy always wins and true love is everlasting, it isn’t reality.

And yet, our society as a whole refuses to address the inevitable truths of life, death, heartbreak, and loss which inadequately and falsely prepare us for the day that we meet these experiences. In the film adaptation of Schwartz’s classic books, there’s a familiar storyline that accompanies haunted locations—the misinterpretation of the past and inflamed legacy of an individual who has passed away. Scary Stories features a character by the name of Sarah Bellows depicted as a sinister spirit who wreaks havoc on a group of friends once her book of self-written stories is stolen. In the end, young protagonist Stella addresses Sarah’s ghost and tells her that she will write her story the way it really was and let everyone know what really happened to her. This is a prime example of reclaiming one’s death (and life) in a manner they choose – a concept that is becoming more commonplace in the funeral industry and is a staple within the Death Positive Movement.

The average American funeral costs $8,000-$10,000, not including the burial and cemetery price tags. Many of the decisions around funeral preparation are made after a loved one dies. As a result, individuals are more easily taken advantage of and choose the most expensive and standard options not knowing for sure what their loved ones preferred to do with their remains, or if there are even alternatives. HBO’s new insightful and tender documentary Alternate Endings: Six New Ways To Die In America aims to introduce viewers to options that may be a better financial, emotional, and environmental fit for their death and the death of their loved ones. The documentary opens with scenes from the National Funeral Directors Association’s (NFDA) annual convention where hundreds gather to display and learn about the latest advancements or trends in the funeral industry. Companies offer the service of decorating personalized caskets, hologram eulogies, and even submerging one’s ashes in the dirt of their native homeland.

The six alternate endings mentioned in the documentary include: a memorial reef burial, living wake, green burial, space burial, “medical aid in dying” (MAID), and a celebration of life. The memorial reef, green, and space burials are all alternate options within the realm of a standard cremation or grave burial. Memorial Reef International builds artificial coral reefs to enhance coral generation, increase marine biomass, and provide eco-friendly alternatives that sustain life for hundreds of years. Another eco-friendly option is the green burial which skips the casket entirely as the body is wrapped in a shroud and placed directly into the earth. This method also bypasses the expensive cost of cement vaults in a standard cemetery which are just meant to keep the grounds even and easier for the landscapers to mow the grass.

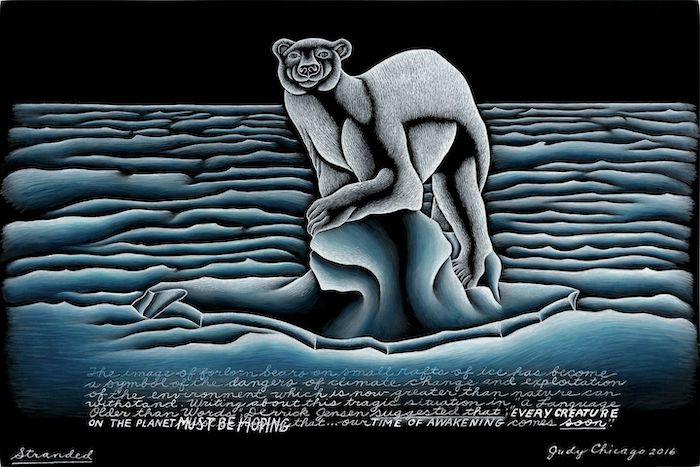

As the effects of climate change grow increasingly dire, more and more people seek ways to give their bodies back to the earth to sustain new growth. Water cremation or aquamation is a form of green cremation which does not emit toxic chemicals nor does it contribute to greenhouse gases. Its carbon footprint is one-tenth of what fire-based cremations produce. In an article by National Geographic, it states “American funerals are responsible each year for the felling of 30 million board feet of casket wood (some of which comes from tropical hardwoods), 90,000 tons of steel, 1.6 million tons of concrete for burial vaults, and 800,000 gallons of embalming fluid. Even cremation is an environmental horror story, with the incineration process emitting many a noxious substance, including dioxin, hydrochloric acid, sulfur dioxide, and climate-changing carbon dioxide.”

The traditional ritualistic aspect of funerals is also evolving. A terminally ill couple in Alternate Endings chooses to have a living wake, a celebration where loved ones and friends are able to say goodbye in person. By embracing their mortality, they’re allowing those close to them to say their final words and experience the appreciation of their life that they may not have realized had they kept their death at a distance. It’s a way to say how much you love someone to their face before you no longer have the chance. Living wakes are performed while the person is still alive and celebrations of life occur after someone has passed. After losing their five-year-old son, two parents in the documentary decide to fulfill their child’s wishes by throwing a party in his honor complete with five bounce houses, painting stations, and an appearance from Batman himself. Even at five, their son realized how sad funerals can be and facing his own death, he specifically requested he not have one.

Now, if someone as young as five years old can embrace their mortality and make a decision about his passing, then why is it so hard for adults? There’s a stigma around death and it is easier to just ignore it as long as possible, but in the end, doing so can be detrimental. In fact, thinking about death can be a positive and productive practice. Mortician Caitlin Doughty understands this and set out to change the way we view death by creating the Death Positive Movement through her work with The Order of the Good Death. “The Order is about making death a part of your life. Staring down your death fears—whether it be your own death, the death of those you love, the pain of dying, the afterlife (or lack thereof), grief, corpses, bodily decomposition, or all of the above. Accepting that death itself is natural, but the death anxiety of modern culture is not.” This is achieved through various resources and advocacy. The name may sound like a cult, but I assure you it’s not.

In her book, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, she describes her idea of a “good death” as being prepared to die, with affairs in order, the good and bad messages delivered, dying while the mind is sharp, and dying without large amounts of suffering and pain. It means accepting death as inevitable as opposed to fighting it when the time comes. Therefore, she has collaborated with an array of funeral industry professionals, academics, and artists to provide the best resources possible including information on end of life planning, green burial technology, as well as methods on how to alter our innate fear of death that has only been enhanced through recent (and unfortunately perpetual) devastating events in the news.

While the horror genre provides viewers the chance to vicariously experience our fear of death in a safe, dissociative capacity, there are now more resources and options than ever before to help us face the inevitable. Instead of solely harnessing terror and sadness, there are ways to find beauty and inspiration in death. As Kafka said, “The meaning of life is that it ends.” Welcoming our mortality allows us to cherish people more because we don’t know how much time we’ll have with them. It is the driving force behind learning, loving, creating, and achieving what we want out of life. While death can be its own scary story, at least there’s comfort in knowing that it is something we will all face one day and there is some control you can have over the process as well as one’s legacy. And when that fateful day comes, let it be the good death you’d want for yourself and those you love, with plenty of peace and the least amount of pain and regret as possible.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!