By Alex Spencer

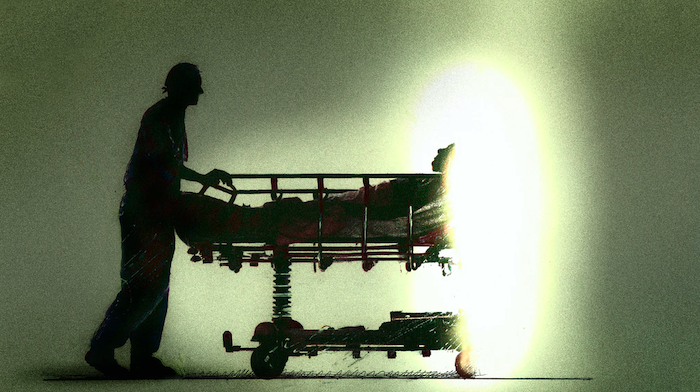

The coronavirus pandemic has forced millions of us to come face to face with death in ways that we never imagined. Whether we’ve experienced personal losses, attended virtual funerals, or watched death tolls creeping up on the news, we are all confronting the pain of illness, death and grief and we’re having different kinds of conversation than we did before.

Researchers from the A Good Death? project at Cambridge University’s English faculty have teamed up with Menagerie Theatre Company to create three original audio plays, released online for free today (Wednesday) to help us to think and talk about this new reality. Written and recorded during lockdown by Menagerie actors, Seven Arguments with Grief, End of Life Care – A Ghost Story and A Look, A Wave are short 15-minute plays that provide glimpses into the thoughts and feelings of a bereaved mother and a hospital doctor, and reflect on the final farewell of the deathbed goodbye.

Written by Patrick Morris, co-artistic director of Menagerie, and inspired by the research of Dr Laura Davies into the history of writing about death, these plays don’t try to provide answers about how to handle what we’re all experiencing, in different ways, right now. What they do is capture personal stories and aim to be authentic to how hard life, death and loss can be.

Laura told the Cambridge Independent: “We have been running them since 2018 to improve conversations about death and dying using literature and the arts that means we run public events such as workshops for bereavement counsellors, people who work in palliative care, hospice workers and we use literature, museum objects and artworks to help people talk about death and dying.

“During the pandemic we built on an existing connection with Menagerie Theatre at the Cambridge Junction to think about how we could make some audio drama that people could listen to at home or on headphones that hopes, in a non-direct way, to help people to think about death and dying in a different way to the headlines of the death toll creeping up.

“We wanted people to think about what they believe and how they are feeling and what their experiences are. Right now we are all being forced to confront a reality that is universal but in a new way. Our ancestors would have been closer to death with it being more common for people to die in the home – child mortality rates were higher and plague and disease that couldn’t be controlled were more usual. We have been protected in the west from that sense that things are beyond our control and that we are quite vulnerable as human beings. You can’t avoid death and dying at the moment and many people are reporting feeling anxious about it, but of course you can’t hide.

“It’s important there’s a way to think about these ideas and listen to a story that can prompt reflections without increasing fear and anxiety. The work of literature and drama is to stimulate emotions,but with a bit of distance because you know it isn’t real. Our message is that death is part of life and that the way in which individuals experience life, death and loss is complicated and unique, andthat there is not a right or wrong way to grieve or a right or wrong way to live your own life knowing it will end.

“The more you talk about it doesn’t make it more likely to happen, but it can enhance the way you live.

“Even if there are elements of death and dying we can’t control, such as where and when and how we might die, it helps to have shared your wishes with your family and to have thought about what you might wish your legacy to be. They can help you to come to terms with it.”

A Good Death? includes workshops designed for practitioners, such as bereavement counsellors and hospice workers, along with public events, creative collaborations and online resources. The project also uses literature and the arts to open up new conversations about death, dying and bereavement.

Laura added: “One of the things emerging in terms of cultural impact is the experience of complicated grief that comes from a traumatic death. Early research points to the fact we are looking at long-term consequences for people’s mental health because they may have experienced not being able to be with a loved one at the end, or only being able to attend a funeral by Zoom. And missing out on those kinds of rituals makes it harder for people to grieve. Psychologists are looking at this cohort of bereaved people and the impact it will have on them.”

Menagerie is a new writing theatre company, resident at Cambridge Junction. It aims to develop and produce new plays which engage powerfully, imaginatively and critically with the contemporary world. Its co-artistic director Patrick explained: “There are so many books about the grieving process as if it’s some kind of logical process rather than something that’s actually faltering, that stalls, that destroys some people, but makes other people. I wanted to create a space for the real difficulties of grief.”

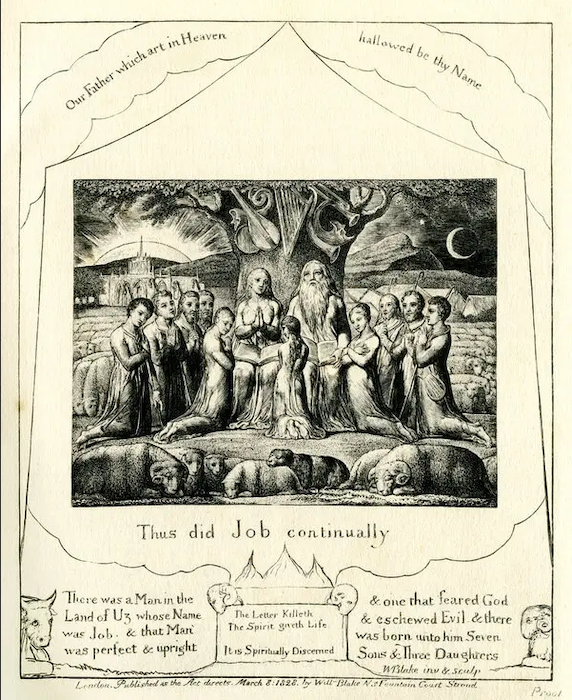

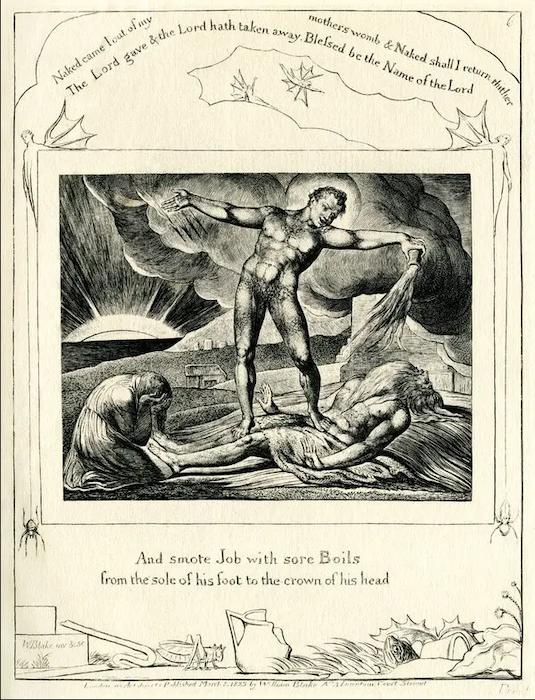

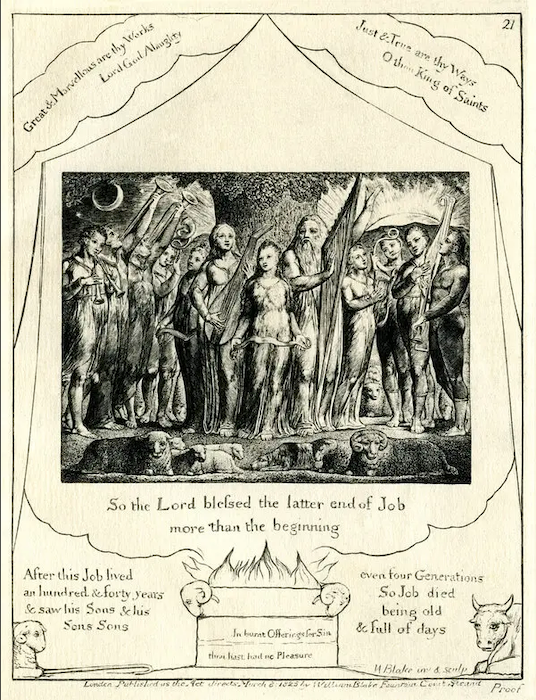

On the value of this collaboration, Laura added: “Working with Menagerie has given me a new perspective on my research into 18th century literature. These plays turn abstract and complex ideas into personal stories, showing new angles that I’ve not noticed before. And they capture brilliantly both how similar our struggles today are to those of the past, and how every person’s response to death or loss is unique.”

The plays can be listened to on the A Good Death? project website, good-death.english.cam.ac.uk/collab , where you can also watch interviews with the researchers, writer and actors.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

I attended my first

I attended my first